NYU’s contradictory attendance policies raise health concerns

Students struggle with vague absence guidelines and apathetic professors.

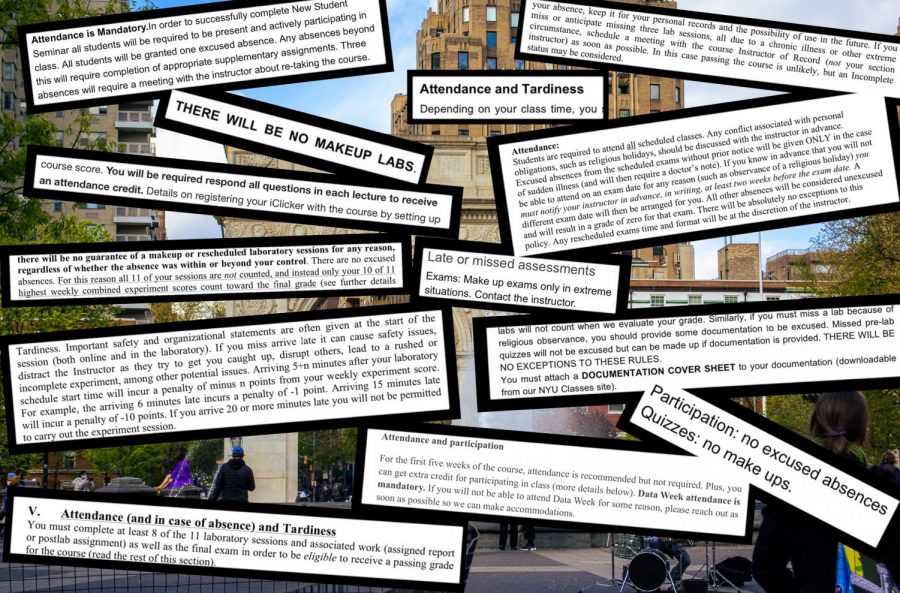

This semester, students find that NYU’s attendance policies contradict with the university’s messaging about student health and wellbeing. The various approaches to attendance policies of different schools and professors are more visible due to continuing effects of the pandemic. (Staff Illustration by Manasa Gudavalli)

November 16, 2021

Tisch junior Meagan Wachtel’s room resembles an art studio. With colored markers and production schedules filling their desk, Wachtel’s dedication to her studies is apparent. However, after the unexpected death of their close friend earlier this fall, Wachtel struggled to attend classes. Despite her open communication with her professors, Tisch’s strict attendance policy forced them to withdraw from a class.

“When tragedy hit, I missed my classes,” Wachtel said. “Obviously, I want to be [in class] and I care. But when something like that happens … you want to take care of yourself … Of course I communicated to my professors. But even after the fact, there was very minimal forgiveness. I had to withdraw from one of my classes because of my participation.”

When Wachtel told her professor about their loss, she was met with icy disregard.

“I was dismissed from the class and told, ‘Sorry you had a rough start, but too bad, goodbye,’ instead of being like, ‘Hey, are you okay? How are you?’” Wachtel said. “That was appalling to me.”

Grief is a heavy burden that requires empathy and support. Attendance policies should not force students to worry about going to class while carrying tragedy’s weight.

NYU’s attendance policy is a scattered collage rather than a cohesive picture, and the return to in-person classes has exposed its faults. Students at NYU global sites have percentage points deducted from their final grade for each week of unexcused absences. At the Leonard N. Stern School of Business, students can miss class due to “documented serious illness,” but not for business trips. The Tisch School of the Arts maintains that “non-justified absences should have a negative impact on a student’s final grade.” At the College of Arts & Science, there is no overarching attendance policy; it’s up to professors.

With mixed messages from NYU’s colleges, students fall through the cracks of the attendance policy’s uneven foundation. Nearing the end of the first in-person semester since the beginning of the pandemic, these cracks are clearer than ever.

Zoe Ragouzeos, the executive director of Counseling and Wellness Services, summarized the NYU Student Health Center’s ideal approach to COVID-19.

“With the continued impact of COVID-19, we have also communicated to our community that the NYU Student Health Center will not issue ‘excuse notes’ to students when they do not attend a class due to a health or mental health reason,” Ragouzeos said. “Students should be taken at their word that they are feeling unwell … Unnecessary visits to the Student Health Center to try and obtain notes can increase the spread of communicable illnesses and impair a student’s ability to stay home and get well.”

This strategy relies on professors and schools to trust that students will advocate for their needs and act responsibly. Dominic Brewer, dean emeritus and professor of education at the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, supports this approach.

“Students should be treated as adults making their own decisions,” Brewer said. “As a professor, my main role is to ensure students learn the material, not that they show up.”

However, this attitude does not extend to students like Gallatin junior Graciela Blandon, who is currently studying at NYU Paris.

“In September … nearly every student at NYU Paris had a cold,” Blandon said. “NYU’s attendance policy de-incentivized students from staying home when sick, so people … showed up to classes with colds, and by mid-September, nearly the entire cohort had gotten sick.”

Blandon emphasized that this policy is not only unfair to students, but also neglectful of — and dangerous for — the greater community.

“If [NYU] had truly made students comfortable with quarantining without risking their academic standing, we could have avoided mass contagion,” Blandon said. “We are extremely lucky that these cases weren’t COVID, but they easily could have been.”

The negative impacts of NYU’s attendance rules also apply to students in quarantine. When Tisch junior Ava Matteucci was exposed to COVID-19, she quarantined immediately. Without a doctor’s note, she was unclear on how this would impact her academic standing.

“My professors have always been very understanding, but not great at defining whether my absence was excused or not,” Matteucci said.

NYU’s contradictory attendance standards have health consequences. An NYU student who attends class sick for fear of academic repercussions can end up infecting countless others. While this lesson should have been learned in 2020, the benefits of NYU’s extensive COVID-19 protocols could be undone by vague and unforgiving attendance policies.

These attendance standards have individual repercussions too — students who fail or withdraw from classes due to illness or tragedy receive a permanent mark on their transcript that can impact their financial aid, cumulative GPA, and future internship or job opportunities. The brunt of this weight will fall on marginalized students, who are already suffering disproportionately from mental health issues during the pandemic. Health-related absences should not be the defining factor of a student’s success or potential because, as Wachtel acknowledges, attendance doesn’t tell the whole story.

“I’m basically on a pass/fail basis in one of my courses, and the only reason I’m in that predicament is because my participation grades are low,” Wachtel said. “[For] my transcript to reflect or make someone look at and think I didn’t work hard when I had to work twice as hard because I had to teach myself everything … [is] unfair.”

Even with such monumental individual and community impacts, professors and students are forced to fill in the gaps of NYU’s ambiguous messaging. Adjunct professor Pamela D’Andrea Martínez, who teaches in Steinhardt’s Department of Teaching and Learning, argues that professors’ positions of power prevent them from accommodating students.

“The disconnect between professors and students [comes from] a position of privilege,” D’Andrea Martínez said. “First, because the professor is seen and understood and believes themselves to be … the person in charge, and what they say goes … There’s definitely an empathy gap and an understanding gap between professors and students.”

Professors have a responsibility to accommodate their students’ circumstances through flexibility, communication and clarity. While NYU schools and the SHC encourage faculty to honor students’ mental and physical health, transforming those suggestions into tangible policies could eradicate student confusion surrounding absences.

To increase flexibility, professors could offer hybrid options to students who cannot attend class in person, evaluate student absences on a case-by-case basis, eradicate grading penalties for absences, and offer deadline extensions to students who need them.

For example, D’Andrea Martínez offers remote options for her class to accommodate different students’ needs.

“My class meets twice a week for three sections, so it’s a lot of class time,” D’Andrea Martínez said. “I’ve cut some of it in favor of people meeting over Zoom for projects, and I just pop into the different projects every week, or they can decide as a group to meet in person.”

While students should stay home if they’re sick or facing tragedy, students should also be responsible for attending class when they can, regardless of penal attendance policies. If professors view students as autonomous adults with independent lives, they can tackle student attendance with greater empathy. This improves communication and collaboration between professors and students.

“The main thing that’s missing [from attendance policies] … is that they are [not] co-constructed with students that have very different life demands and experiences,” D’Andrea Martínez said. “When you have that sort of communication, then those policies are going to be better.”

Though forced to withdraw from one class, Watchel has co-constructed a schedule with their Introduction to Animation class professor Christen Smith.

“I had a fair amount of issues in my participation because of things going on in my life,” Watchel said. “[Smith has] really taken a care and account into me and my development as an animation student, and there’s been no judgment with regards to my circumstance … If anything, she’s been incredibly sensitive and caring towards it.”

Attendance policies affect more than just empty rosters and fluctuating letter grades. For many students, they can be the difference between academic success and failure. When more professors communicate with their students and provide flexible attendance policies, students can thrive in classrooms where they feel supported — even when life happens.

Contact Ava Emilione at [email protected].