Review: ‘All the Beauty and the Bloodshed’ is a stunning portrait of Nan Goldin

Laura Poitras’ documentary about Nan Goldin chronicles her life through art and activism.

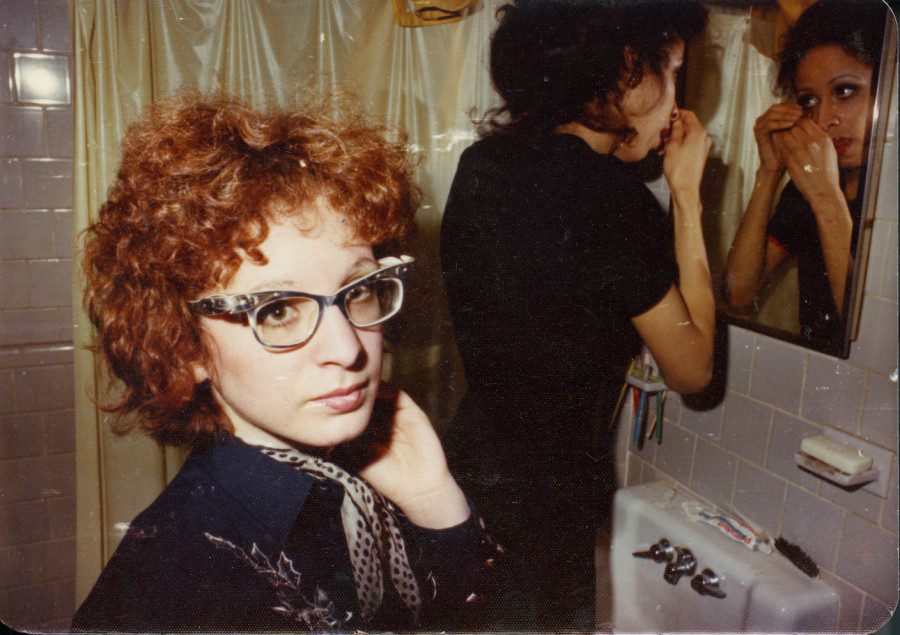

“All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” follows documentary photographer Nan Goldin. The film is available in select theaters. (Courtesy of Nan Goldin)

November 11, 2022

Laura Poitras’ striking documentary “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” juggles many topics without losing sight of the film’s subject: photographer and activist Nan Goldin. The film delves into Goldin’s past and how it impacted her vision as an artist, which later informed her activism.

The documentary moves in chapters using title cards to separate the periods of Goldin’s life. Every chapter interweaves her art with her activism, creating a tapestry explaining what led her to become passionate about showcasing marginalized communities through her art.

“All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” opens with Goldin taking legal action against the Sackler family, the owners of Purdue Pharma, a company responsible for overprescribing addictive prescription drugs. The Sackler name was formerly emblazoned on famous art museums such as the Tate group, the Guggenheim, and the Louvre Museum, as they have donated to many art institutions. The film opens with Goldin’s 2018 protest of the Sackler Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Goldin and fellow demonstrators threw pill bottles in the moat’s water at the Temple of Dendur exhibit while chanting, “Sacklers lie! People die!”

Goldin’s formation of the group Prescription Addiction Intervention Now, and the organization’s actions against museums which held Goldin’s work in their permanent collection, provides the framework that forms Poitras’ image of Goldin. It is revealed that Goldin was addicted to OxyContin and suffered an overdose before becoming sober.

Scenes of Goldin’s activism are paired with vivid flashbacks of her recounting her childhood and the suicide of her older sister Barbara. Goldin blames her parents for her sister’s suicide, claiming that they were unfit to have children. Goldin cites Barbara’s avoidable death as the spark that started her rebellious spirit, and the start of her life and activism.

Following her sister’s death, Goldin’s parents send her to foster care with hopes that she wouldn’t suffer the same fate. After feeling like an outcast for many years Goldin finally found a family among East Coast LGBTQ+ communities, where she also discovered the power of photography.

The film details her shift into adulthood describing her move to New York and her various sex work and bartending jobs. During this time Goldin began sharing her photography and started her most notable collection, “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency.” The show focuses on sexual images of Goldin and her friends, defying the norms of typical art at the time. Goldin found power in the camera, using art to shape her activism.

The most poetic piece of the film is when Goldin’s activism during the AIDS crisis is layered over her legal action with PAIN. Although the AIDS crisis and the opioid epidemic differ greatly, Poitras uses Goldin’s passion for the fight against AIDS to contextualize her dedication to PAIN and the fight against the Sacklers. Poitras braids these two strands of Goldin’s activism, focusing on an art show she curated showcasing the art of her friends suffering from AIDS.

This documentary captures many of Goldin’s successes as she learns about the impact of her legal action — the Sackler name has been taken out of museums worldwide. Goldin’s joy and enthusiasm come across very clearly throughout the film, despite rarely showing Goldin’s face during interview portions. While Goldin is a great speaker and the archive footage used was beautiful, it would have felt more intimate if the audience could see Goldin as she recounts her life in great detail and emotion.

Goldin’s work is raw. The film in the documentary is not perfect, sometimes the camera shakes and zooms awkwardly, and at one point there is a blurry finger peeking into the frame. The imperfections seem almost purposeful, mirroring her work. This decision makes the film feel more real and shows a more accurate portrayal of Goldin, who reveals her imperfections time and time again.

“All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” is a tribute to the power of art as it weaves many parts of Goldin’s life together to reveal how her art was shaped by her activism and passion, and how her views and opinions were aided and influenced by her art and the artistic process.

Contact Saige Gipson at [email protected].