Langone Discovered New Organ in the Human Body

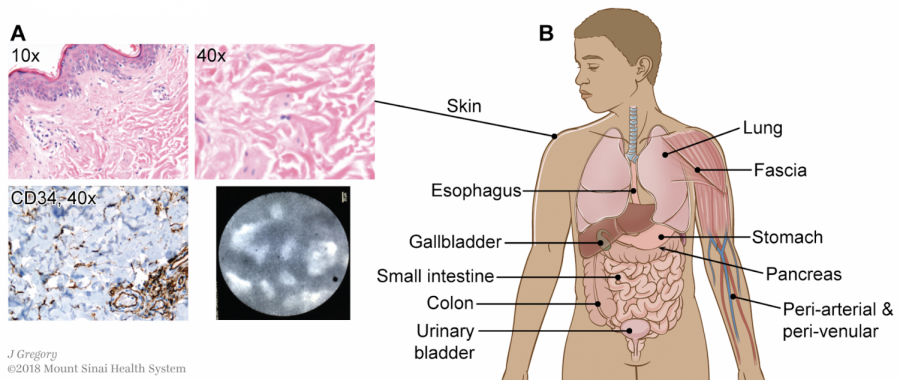

A body diagram depicting the layers of skin cells.

April 6, 2018

A groundbreaking study co-led by NYU Langone Health has recently discovered a new organ in the human body. The team of researchers said that they have found a network of fluid-filled spaces in tissue that hadn’t been seen before. They claim the new organ could be the largest in the human body.

Their finding made a media splash, having been featured in National Geographic, Scientific America, The New York Times and CNN among others. While some researchers dispute whether their finding does indeed qualify as an organ, if agreed upon, this finding could alter textbooks and biology as it is currently known.

Before this discovery, most scientists thought that collagens — the main structural protein found in skin and tissue — were the protein glue that held tissues together. However, the new finding shows that the textbook model for a dense bundle of collagen located underneath the epidermis is incomplete.

During this research, the scientists noticed fluid-filled spaces supported by many collagen bundles in the living tissues of bile ducts, where they expected to see a thick connective tissue layer. To discover why this was the case, Pathology Department Professor Dr. Neil Theise and his team froze a thin slice of tissue from a removed bile duct to observe the tissue in the state prior to being put on a slide.

“By observing the tissue, we confirmed that there were these open spaces separated by collagen bundles,” Theise said. “And that’s when we realized that when you take tissue out to make a slide, the fluid drains from these spaces. So they collapse and the collagen bundles fall on top of each other, creating the appearance of a dense connective tissue layer, but it is in fact, artifact.”

Theise also stated that this is the reason these fluid-filled spaces weren’t discovered until now.

“It just sort of disappeared in processing,” he said.

Director of Endoscopic Surgery at Northwell Health Petros Benias said that when tissues are extracted out of the body for dissection, there exists no dense tissues of collagen.

Instead, there is a collapsed compartment of tissue and fluids called the interstitium — the newly discovered organ.

“The most important thing to understand is that the word intersitium is not a new word,” Benias said. “What we’re doing is broadening what it refers to because the interstitial space classically refers to the space between two cells.”

Benias said that the fluid-filled spaces served the same function and are distinct from other body tissues. As a result, they deserve to be referred to as an organ. He believes that they have specific features that classify them as an organ.

“The definition of an organ is that it has a very specific structure and it serves a very specific function,” Benias said. “Structure we’ve proven, function we’re alluding to because it seems to be that there’s a lot. It is important for fluid redistribution and cells traffic through the space.”

Theise stated that this new organ served particular functions such as the generation of lymph into the lymphatic system and production of electrical signals, which confirms it as an organ.

Regarding its repercussions to human health, Theise, Benias and Co-author and clinical director at Weill Cornell Medicine David Carr-Lock said that this newly discovered organ contributed a role in the spread of diseases.

“This is a large organ network that’s really spanning everything,” Benias said. “It’s probably got implications for inflammation, autoimmunity, even cancer spread.”

With the recent publishing of the study, some questions still surround the findings. Benias said that one of the major questions was the public’s definition of the word intersitium.

“People might think they’ve known about the intersitium for years, but we don’t, actually,” Benias said. “We know about the microscopic individual space, which we used to call the interstitium. But this is a very large macroscopic network; it’s beyond the field of view of the naked eye that spans the entire organ and the entire tissue. It’s important to understand that this is a completely redefinition of the entire interstitial network.”

Carr-Lock noted a possible source of contention surrounding the findings.

“People might argue that [the discovery] is not new,” Carr-Lock said. “An interstitium has been recognized for centuries but as a passive space only. “We are suggesting that the interstitium is an active interconnected space for fluid passage, cell movement and collagen formation.”

To move forward with the study, Carr-Locke said that many questions still remain that may be addressed by different groups interested in others aspects of this space such as cancer specialists, fluid mechanics, immunologists and even acupuncturists.

“We shall attempt to develop endoscopic sampling techniques from the interstitium to validate some of these phenomena,” Carr-Locke said. “We shall also try to integrate other observations that might now be explained.”

Email Christine Lee at [email protected].