We are both Asian, but we look nothing alike

It’s not too late to recognize your subconscious microaggressions and how they induce anxiety and doubt.

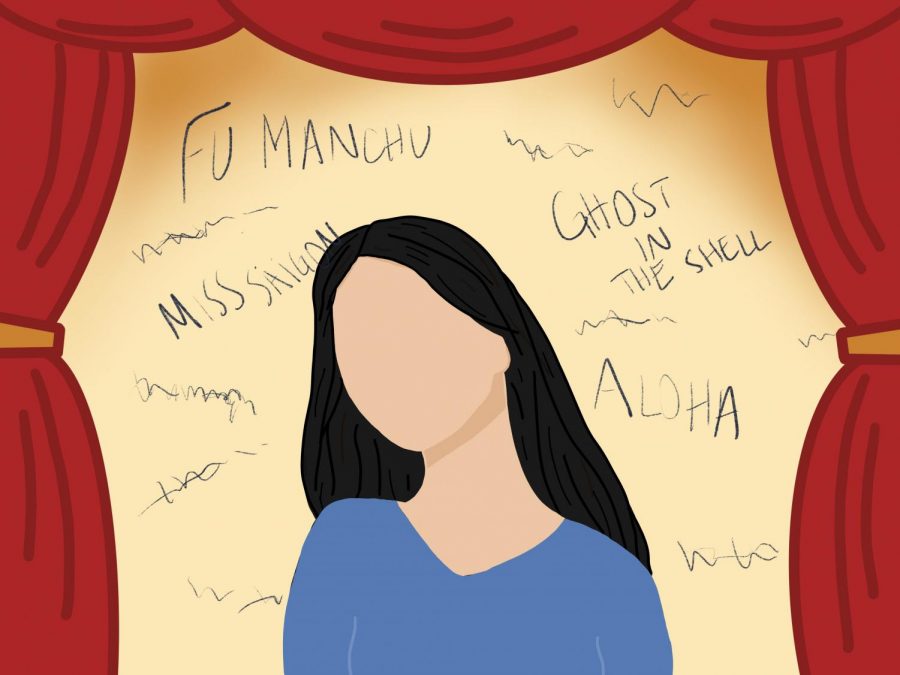

Despite not looking or behaving similarly, Asian actress students are constantly mixed up by their NYU professors. U.S. media perpetuates racial microaggressions by either having stereotypical Asian characters or having white-washed characters played by white women. (Staff Illustration by Manasa Gudavalli)

August 25, 2021

It’s almost the year-and-a-half anniversary of the last time I performed for a live audience, and let me tell you: this has been the most maddening, daunting and self-doubting time to be an Asian actress.

When NYU Albert released grades at the beginning of this summer, I nervously checked my transcript and immediately felt relieved. I told my Asian American friend and fellow Meisner Studio sophomore Kelly Wong that my grade seemed fair, yet I couldn’t help but think about what was making me anxious. Before clicking the “Grades & Transcript” button, I was afraid that I would get someone else’s grade because of my race.

Rather than examining to what degree racism exists in theatre nowadays, I’m here instead with the fear of being judged and criticized for being too sensitive, vulnerable and fragile. After years of anti-racism protests, some may say that there are fewer loathsome stereotypes in the industry now — as in the slanty-eye yellowface makeup of Fu Manchu, the Western fantasy of Asian women in “Miss Saigon,” or the “can you be more Black” question my white director asked my best friend who played Richie in “A Chorus Line.” However, racism doesn’t only include stereotypes. It manifests in different ways — indirectly, subtly and even unintentionally.

At the end of Spring 2021, one of my studio professors called Wong by my name during rehearsal. This was no isolated incident. Wong and I were misidentified repeatedly. Aside from being in Meisner, we have very little in common. Wong has longer hair, an oval face and wears lighter makeup while I have higher cheekbones and a wider face. She is more lovable and humorous whereas I’m more whimsical and energetic.

But most prominently, we are both Asian.

I was willing to ignore the first mix-up, convincing myself that maybe we had been dressed alike that day on Zoom, yet it continued to happen throughout the semester. While we both knew how anti-racist this professor was and felt that she was one of the kindest professors we’ve had, this mix-up felt like a manifestation of racial microaggression. Due to her well meaning nature, it could be easily explained as an accident that nobody should take it to heart.

Then why do we feel offended? The impression that this professor subconsciously thinks that people of a race other than her own, (in this scenario, Asian) all look alike. I wonder if there is nothing else that stands out except my Asian identity. I’m not saying that I’m not proud of my identity, I am, but I’m more than a race and ethnicity. Is there nothing else that can help people remember me? Why can’t I be remembered by that monologue I performed or the sonnet or poem I practiced for so long? I used to tell myself it was no big deal, but as it happened in class, student evaluation and rehearsal, the buildup became demoralizing.

Some studies and news articles, including one published by Forbes, however, have viewed it from a more optimistic and benevolent angle.

“We humans are notoriously poor at distinguishing between the members of races different from our own,” journalist Steven Ross Pomeroy said. Sure, some of us Asians do actually look alike, but the writer takes it one step further.

“The Other-Race effect is not necessarily fueled by racist thinking,” Pomeroy said. Instead, he summarizes two hypotheses that explain the effect: people tend to tune out characteristics of members of other races and spend more time with people of their own race.

If you’ve only seen me or taught me a couple of times and barely spent time with Asians, of course it would be understandable. But, if these mixups kept happening for a whole semester — after about four months of two classes per week, two hours per class — should we still blame it on the “spend more time” and categorical thinking hypotheses?

White people can also be on the receiving end of the cross-race effect when they are the minority in the workplace. An article published by the Washington Post interviewed a white English teacher who was misidentified by a stranger in China. Given the Han ethnic group makes up over 92% of China’s population, white people become the minority.

However, the U.S. media differentiates between white people much more than people of other races. The overrepresentation of white people in U.S. media is an obvious but understated point. Asian characters have been whitewashed in past films. In the adaptation of the anime “Ghost in the Shell,” Scarlett Johansson — who is not Japanese — was cast as the protagonist to play the lead role of a Japanese woman. In “Aloha,” Emma Stone was cast as Allison Ng, who is one quarter-Hawaiian and one quarter-Chinese. Although I love these talented actresses, I am disgusted by Hollywood’s marketing choice of casting white actors as film leads just to make Asian characters more tempting for its white audiences.

“Films with leads who were people of color or women were more likely to have smaller budgets in 2020 than those with White and male leads,” Dr. Darnell Hunt and Dr. Ana-Christina Ramón said in UCLA’s latest Hollywood Diversity Report. The report also shows that Latinx, Asian, Native and MENA persons were all underrepresented among film leads, and only 5.4% of leads were played by Asian actors.

So the third hypothesis of the Other-Race effect, as I see it, would be the lack of representation of minorities in different societies. When I was in high school, I fantasized about being a white girl, having blue eyes and blond hair, so I could be cast as the lead in a Hollywood film. But in imagining so, I realized the issue of underrepresentation more candidly. We need to be more conscious of whose stories are being marginalized in mainstream media and how it impacts marginalized groups. In that case, we could avoid the issue of misidentification by demanding more visibility of underrepresented groups in the media, film and theatre.

The mix-up itself is prejudice and ignorance not based on how similar Wong’s acting skills and mine are, but our ethnicity, which instills doubts and anxiety in our sense of self and talent over time. I don’t know how much this has impacted me because I don’t know if anyone else in my department has mistaken me for any other Asian actresses besides Wong. I don’t know if I have received compliments or feedback that are not meant for me. I don’t know if they can appreciate and differentiate our work. I don’t know if my work really matters if I simply fall into the category of Asian actress. It creates this sense of uncertainty in what I do as a performer moving forward.

I’m still having a hard time defining this name-miscalling situation. That’s why I never reached out to have a conversation with this professor — whose work I truly respect and admire. I was afraid of accidentally feeding into the stereotype: all Asian women are sensitive. However, I will choose to address microaggressions if they happen again.

Sure, you may be wondering if the professor should be censored or canceled, but that question itself distracts people from my point: people should be aware of their biases and impact regardless of punishment. We’re all human beings, prone to mistakes, and we all might commit microaggressions subconsciously. It doesn’t mean that we are horrible people but we need to be more aware of our biases and their corresponding impacts on others.

We all need to make the effort in order to create a more harmonious working environment. As students, if we encounter this unpleasant circumstance, we shouldn’t be afraid to reach out to stage managers, advisors or studio administrators, and let them bring this issue up in staff meetings more often, specifically and seriously. At the university level, NYU should host more lectures on the topic of diversity and inclusion not only for students but also for professors and staff. At the industry level, influencers should speak up in support of diversity, equity and inclusion. If we put actors on screen and on stage regardless of race and ethnicity, people will learn that skin color is just skin color. Then, hopefully, the “spend more time with people of our own race” hypothesis will not continue to be an excuse for misidentifying and marginalizing minority groups.

Email Jennifer Ren at [email protected].