‘Pollock & Pollock’: American labor history through abstract expressionism

The unconventional documentary, depicting the Pollock brothers’ complicated relationship with the political legacy of abstract expressionism, is currently streaming on Ovid.tv.

December 15, 2022

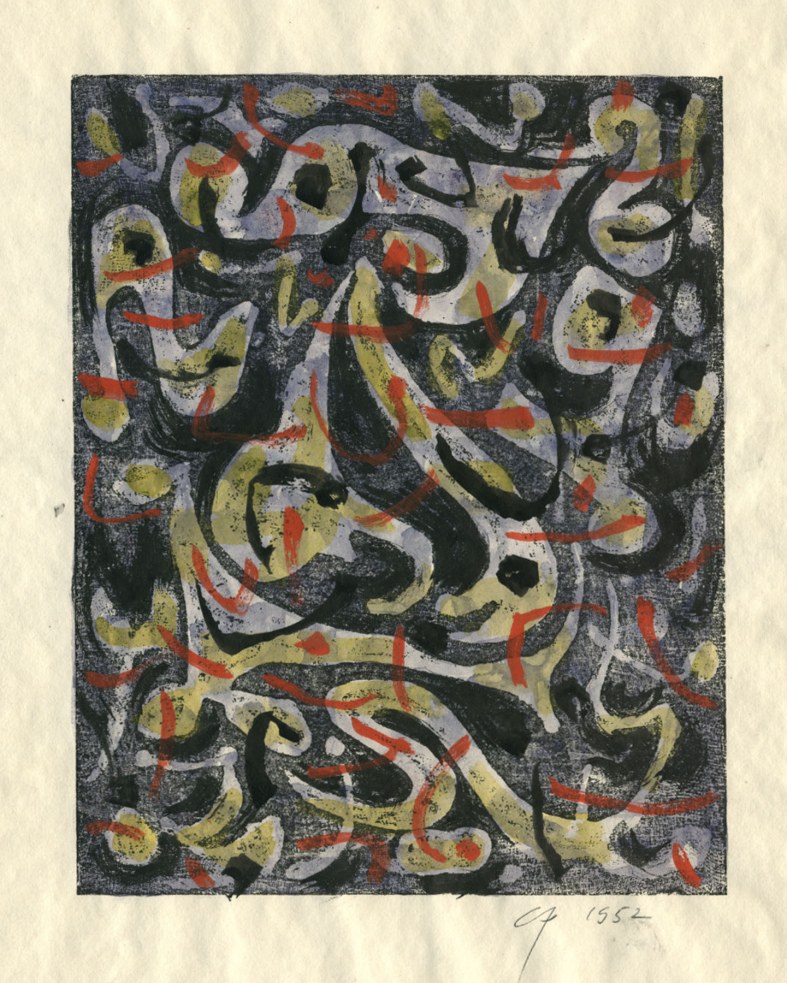

Abstract expressionism retains its purchase in contemporary discourse due in large part to its role in American cultural policy. During the Cold War, it was the favored aesthetic movement of the CIA, who used its artists to symbolize the triumph of American freedom — of expression and markets alike — against Soviet communism. Abstraction offered a potent antidote to the socialist realist style that dominated Easten European culture production.

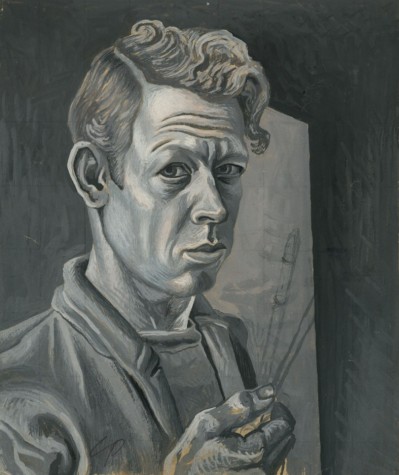

“Pollock & Pollock,” Isabelle Rèbre’s 2020 documentary about the relationship between brothers Charles and Jackson Pollock, offers a counternarrative to this political legacy. The documentary, told in epistolary form, highlights the critical role social realism played in the Pollock brothers’ development as painters. Rèbre’s attention to this largely elided family’s political history offers a sharp counter to the mythos of Jackson Pollock, a famous CIA weapon.

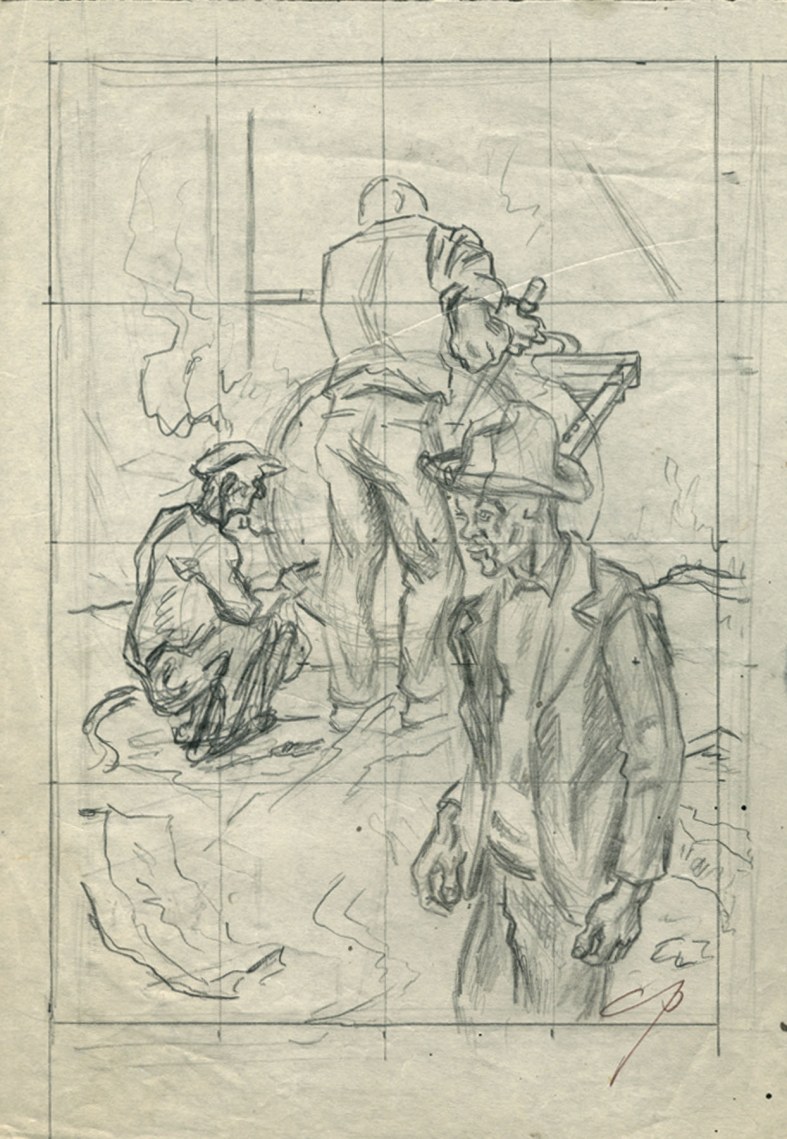

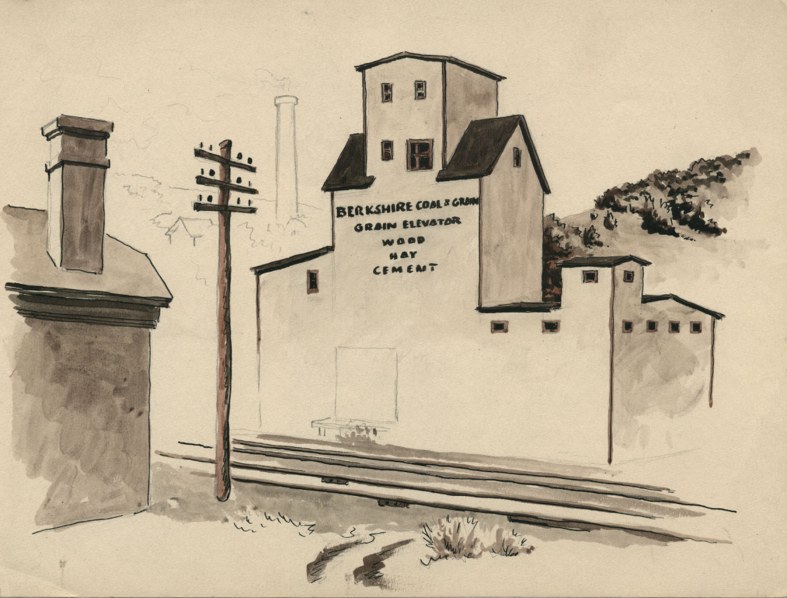

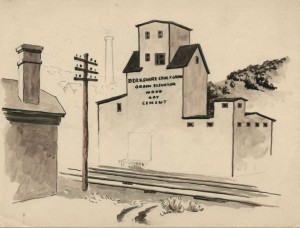

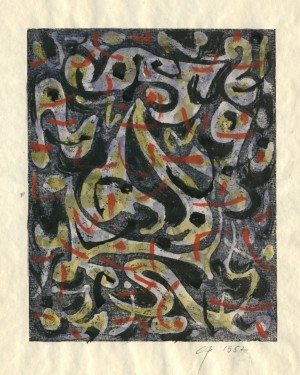

It is jarring to reconcile the political legacy of a movement nicknamed so blithely by Nelson Rockefeller as “Free Enterprise Painting,” with the Pollock brothers’ origins among a variety of disputing left institutions. As the letters narrate, these range from Franklin Roosevelet’s Works Progress Administration to the United Auto Workers to the Communist Party USA. Rèbre uses the family drama of these letters to explore the surplus of institutional and cultural transformations that brokered American aesthetic politics during the 20th century. Charles’ gradual turn away from social realist aesthetics toward abstract expressionism parallels these changes.

Structurally, the film leans into archive fever. Rèbre favors shots of Charles’ wife and daughter, Sylvia and Francesca, respectively, combing through the letters and gingerly handling his unseen artwork. She pulls unused footage from Hans Namuth’s famed 1951 documentary short, “Jackson Pollock 51.” Yet she maintains a clear anchor in the present, placing voiceover readings of these historic letters over footage of present-day New York City.

Anyone who has spent time in Washington Square Park over the last several years will recognize the “This Machine Kills Fascists” sticker emblazoned on the grand piano of a busker who recurs throughout the film. It quietly evokes the Pollock brothers’ despair in response to the growing fascism in Europe of the 1930s and 1940s, which remains a key point of concern over the course of this decadeslong correspondence.

Toward the end of the film, Sylvia watches the Donald Trump election. Her despair is reminiscent of Charles’ tone in his letters written around the time of his departure from America in 1970: “America seems such a lost place right now. We can’t quite face the hopelessness of it all.”

“Pollock & Pollock” draws its focus from this very slippage between emotion and politics, evident throughout Charles’ transition from social realism to abstract expressionism.

As American painting splintered from left political institutions, Charles’ abandoned social realism and murals in favor of abstract expressionism. His crisis of faith in the future of the American left motivated his relocation to France in 1970, by which point he was “utterly disgusted by American politics, the Vietnam war, etc.”

A sly documentarian, Rèbre sustains a clear political history without compromising the decision to let the Pollocks speak for themselves. Their correspondence highlights how, as Charles grew increasingly fatalistic about the state of left politics in America, he turned away from its dominant mode of aesthetic expression — social realism. This turn is critical to understanding the politics of the now towering movement of abstract expressionism.

As seen within the film, Charles’ careful effort to guide Jackson through periods of depression, disillusionment, and creative drought reveal a contrasting account of his artistic practice. Their letters highlight the years of slow labor and the conscious cultivation of a steady work ethic that preceded Jackson’s most celebrated years of output in the 1950s. He writes to Charles about his desire to buckle down and work: to learn how to be an artist by laboring away at his medium.

These anxieties, both familial and political, surpass a merely biographical register to instead explore the ambiguities that were typical of the political left and artistic vanguard that surrounded the Pollock brothers.

Contact Natasha Roy at [email protected].