“Breasts and Eggs” by Mieko Kawakami

— Alexa Donovan, Deputy Arts Editor

At first, I felt silly reading a book called “Breasts and Eggs” on a crowded subway — now, I feel like I’m carrying a bar of intellectual gold. Mieko Kawakami’s book, translated from Japanese by Sam Bett and David Boyd, is a deeply philosophical novel that grapples with the weight of having a female body.

“Breasts and Eggs” is a novel split into two parts telling the story of three women in contemporary Japan. In Book One, the narrator, Natsu, is visited in Tokyo by her sister, Makiko, and niece, Midoriko. Makiko travels from Osaka to get breast implants, and visits her sister while she’s there. Meanwhile, Midoriko refuses to speak to her mother or her aunt, only communicating through writing in her journal. In Book Two, readers revisit Natsu 10 years later, as she contemplates having a child on her own, which is illegal.

The book was admittedly a slow read, as nothing really follows a plotline. But there are so many layered themes to explore through Natsu’s contemplation of life. Kawakami confronts topics such as fertility, bodily autonomy, sexuality, femininity and womanhood with sharp prose and a surprising amount of humor. I felt deeply moved while reading the novel, and was even overwhelmed by the prospect of having to express my thoughts in such a short review.

My grandma, who is halfway through the book right now, also recommends it.

“Exteriors” by Annie Ernaux

— Marisa Sandoval, Contributing Writer

A story presented through journal entries over seven years, “Exteriors” by Annie Ernaux takes readers along as she seamlessly slips into strangers’ day-to-day lives on the outskirts of Paris. This book is a great companion for anyone prone to staring or eavesdropping on the subway.

Written with humility, curiosity and an observer’s eye, “Exteriors” allows readers to reflect on the subtleties of humanity from a position of anonymity. The themes of sexism, classism and inequality in contemporary France arise by way of Ernaux’s scrutiny.

As she watches others, Ernaux reflects on herself. She warns readers not to just lie refuge in their journals, but to engage with the world to learn about themselves. This book does not follow a structured plot, but instead characterizes the spontaneous and lyrical beauty of observation. By Ernaux’s side, I am likewise, forever combing reality for signs of literature.

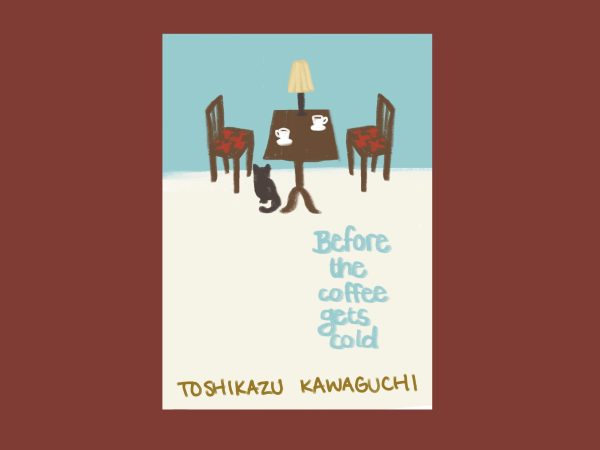

“Before the Coffee Gets Cold” by Toshikazu Kawaguchi

— Juliana Gurracino, Culture Editor

“Before the Coffee Gets Cold” follows four characters who visit a cafe in Tokyo where people can travel back in time — but only until their coffee gets cold. Each character hopes to revisit past memories and people, but of course, that doesn’t come without consequences.

I was initially drawn to the story because, admittedly, I will buy any book with “coffee” in the title or a cat on the cover, but in the end, it was surprisingly moving. This book is not going to have you on the edge of your seat, but it will pull at your heartstrings enough to keep you invested. And yes, I did cry at the end — you’ve been warned.

What I loved the most is how simple and real the story feels despite the sci-fi twist of being able to time travel, albeit with many rules. Though the writing isn’t particularly evocative, it is still very detailed — I had a clear movie playing in my head with every page. The characters, particularly the women, were at times cliche, but their emotional connections to one another effectively grounded the piece. By the end of the book, I wished for more stories — luckily there are four books in the series.

“Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice, and London” by Lauren Elkin

— Maggie Turner, Contributing Writer

“And it’s the centre of cities where women have been empowered, by plunging into the heart of them, and walking where they’re not meant to.”

Flaneur — a French term for a male, observant city goer — is a word popular in art history, but linguistically excludes women. Writer Lauren Elkin coins the word Flâneuse, a word based on the women who walked the streets before her. In cities from Paris to Tokyo, Elkin revolutionizes a practice embedded in its own rebellion.

Cities would be nothing without the women who scour their corners. Elkin explores the stories of women from the past: Martha Gellhorn, Jean Rhys, Sophie Calle, George Sand and, of course, herself, through her own past lives. Elkin’s personal anecdotes connected with the cities mentioned and the creative material born from their respective flâneuses create a layered history. This book is essential for any NYU student finding their path in the city, proving even a walk down a new street holds history beyond what meets the eye.

Contact the Arts Desk at [email protected].