Review: Edward Hopper’s art showcases his hatred for NYU

“Edward Hopper’s New York,” a love letter to New York City, is on view at The Whitney until March 5, 2023.

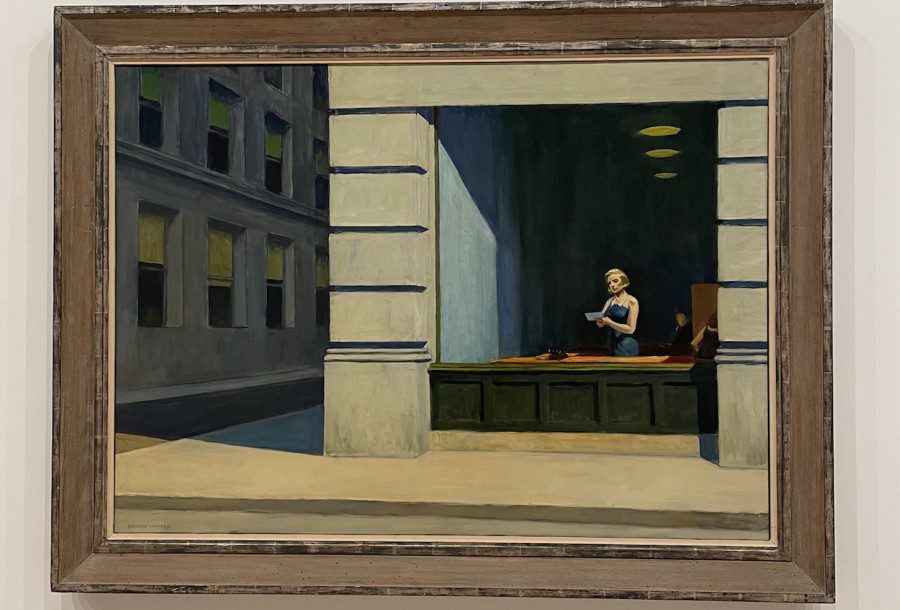

New York Office by Edward Hopper, 1962. “Edward Hopper’s New York” is available at the Whitney Museum of American Art. (Clara Scholl for WSN)

November 22, 2022

Edward Hopper’s 1945 painting “August in the City” depicts the side view of a rounded window protruding from an elegant brownstone. The urban house, adorned with yellow curtains and marvelous architectural moldings, basks in the sunlight of a summer day in the city. This scene, along with the rest of his paintings, shows Hopper’s unique understanding and appreciation of New York City, as well as his desire to keep that spirit intact.

Hopper is one of the most celebrated American artists of all time, and a key figure of Greenwich Village. Having lived in New York City for almost 60 years, with the majority of that time spent in his home studio at 3 Washington Square North, Hopper devoted nearly all of his artistic focus toward the community he knew best — Greenwich Village.

As an homage to Hopper, the Whitney Museum of American Art has dedicated nearly its entire fifth floor to “Edward Hopper’s New York.” From Oct. 19, 2022 to March 5, 2023, the exhibition will showcase 3,151 pieces by Hopper and 8 pieces by his wife, Josephine Nivison Hopper. While the exhibition’s scope is large, the subject matter is highly personalized. The New York City that Hopper worked to capture in his canvas does not look much like the city we know today. Hopper loved the small details and personal aspects of the city, but which have now been lost to gentrification by the likes of institutions such as NYU.

Curated by Melinda Lang and Kim Conaty, “Edward Hopper’s New York” showcases an overwhelming number of works that are expertly categorized into seven different themes: The City in Print, The Window, The Horizontal City, Washington Square, Theater, Reality and Fantasy and Sketching New York.

As the viewer enters the floor, they are introduced to a diverse collection of artworks in various sizes. The first piece, in a corner of the floor, is Hopper’s oil painting “Approaching a City.” Inspired by the railroads that bring commuters into Manhattan, Hopper uses a muted color palette to depict the rider’s view of the city’s great buildings looming over the horizon of train tunnels. Perhaps the train ride into Manhattan serves as a direct parallel with how Hopper wished to show his audience his personal and idealized New York City.

“The Horizontal City” showcases New York City through an uncommon lens. By focusing on the city’s width rather than its height by way of skyscrapers, this area of the exhibition demonstrates Hopper’s proclivity for playing with perspective. His imaginative views of the city project his ideal version of it — one without real estate moguls like NYU.

The artworks of “Reality and Fantasy” showcase Hopper’s exploration of the inner lives of individuals against the backdrop of the city, helping define a subject’s place within their setting. “Sketching New York” helps the viewer understand Hopper’s mind and what he chose to focus on within Manhattan. His focus on the ordinary made New York City a very personal place, a place of real people, buildings and humanity. Finally, “Washington Square” includes artworks inspired by the view from his window, such as scenes of Washington Square Park and other artifacts in the Village at the time.

Within this section, the 1928 piece titled “My Roof” depicts the roof of Hopper’s old Washington Square apartment. The uneven rooftop and tin details draw parallels to the apartments that NYU students live in today.

Despite the passage of time, Hopper’s work is still relatable for New Yorkers due to the spirit it holds, even if aspects of the Village that Hopper knew are now gone. The far-out views Hopper painted depict a bygone time, now replaced by towering NYU buildings. This is not to say the landscape has been ruined by NYU’s real estate escapades, but the beauty of the city has been changed in some insurmountable way. There is less depth in views of the city from Washington Square.

These obstructions are exactly what Hopper fought against. While it is perhaps unimaginable to us, there was a time when the park was not surrounded by NYU buildings. Dorms and student centers did not surround each direction of Washington Square. While not an official campus, the park is the closest NYU students have to one. Before NYU, the scene of the Greenwich Village was a work of art in and of itself — some of these buildings limited the great flourishment of art.

NYU’s presence in Washington Square Park has significantly contributed to New Yorkers’ discontent, as seen in newspaper headlines like “Washington Square Artists Rise In Protest — NYU’s Evicting Them (NY Post, 1947)” and “Washington Square Evictions Arouses Art Colony in Village: ‘Do They Want to Turn the Square Into an N.Y.U Campus?’ (The Sun, 1947).” The area was a safe haven for artists, but NYU’s emergence in the neighborhood quickly crushed the dreams of many who found themselves displaced by the university.

This Greenwich Village takeover was an issue close to Hopper’s heart. He strongly advocated against the use of the area for NYU’s endeavors. In letters written to New York City Department of Parks & Recreation and the Washington Square Association, which are presented in the exhibit, Hopper fought endlessly to save the neighborhood from further encroachment: he exclaims that he was “strongly opposed to any further desecration of Washington Square by New York University or any other large commercial interests” as “Washington Square should be preserved by the efforts of all of our citizens, if it is humanly possible to do so.” Hopper even went so far as to offer honorary members of NYU’s faculty homes and studios away from the park, all for the sake of protecting the neighborhood.

The most striking detail about Hopper’s vision of the city is that his works don’t exactly depict what anyone would expect to see. While most artwork of the city focuses on its vertical longitude — skyscrapers, the architecture and world-famous views — Hopper zoomed in. His street-view pieces depict bridges, train tracks, storefronts, windows, theaters, restaurants and more, showing us a more personalized image of the city. Instead of focusing on the big picture, Hopper focused on the small things that work together to make the city whole.

Through pieces like Hopper’s 1958 “Sunlight in a Cafeteria,” which depicts a girl sitting in a cafe, or his 1930 “Early Sunday Morning,” which portrays a quiet village barbershop, the audience glimpses the day-to-day life of New York City years ago.

Edward Hopper said that he wanted to “project upon canvas [his] most intimate reaction to the subject as it appears when [he likes] it most,” which is exactly what he did. He focuses on the smaller aspects of New York City and life there, a skill that is perhaps what makes somebody a New Yorker. In a city that is always moving, and always changing, it makes sense that we pick and choose what to focus on. For many, it is the smaller details of New York City that makes the city feel like home. To Hopper, that was displaying his New York in microscopic ways.

Contact Alexa Donovan at [email protected].