Middle East Archive uses photography to break dehumanizing depictions

Middle East Archive offers candid portraits of Middle Eastern life and culture.

November 9, 2022

Middle East Archive is an online record of photographs depicting everyday life in the Middle East. None of the images in the archive are staged; no one is forced to wear a turban in the middle of the desert or asked to solemnly stare into the camera in front of a damaged building. Rather than playing into Orientalist fantasies, the images narrow the scope to the candidness of the scenes. The archive’s Instagram posts each contain nothing more than a photo, a short curated description of the location and the name of the photographer.

These photographs counter Western media’s typical portrayal of the Middle East as backwards and war-torn. Western media typically represents Middle Eastern life through the lens of violence, while the archive does so through a humanistic lens. It produces visual proof of the deeper aspects of Middle Eastern culture that expand beyond Western perceptions.

Many of the photographers that contribute to this archive are outsiders — people that were not born into Middle Eastern culture. Generally speaking, outside photographers tend to force the viewer to think about the journey of a captured image, steering attention away from the image’s subjects. These photographers might then be acknowledged for enduring daunting tasks vis-à-vis their exploration of a seemingly controversial part of the world.

The story then ceases to be that of the Middle Easterners, but of the heroic and admirable qualities of the outsider — an outsider who probably never experienced the overwhelming joy of doing dabkah with their friends or watching their grandmother flip over the massive pot of maqluba for dinner. However, the photographers featured in the Middle East Archive find ways of removing themselves from the picture.

The photographers exhibited by Middle East Archive actually engage with the people and cultures they are exposed to and candidly let them appear as they live in the images they take. As seen in the image above, it appears that the photographer didn’t tell the little girls to look into the camera with eyes of longing and helplessness. Instead, the children continue about their lives without interruption. Some of the girls appear to look towards the camera out of sheer curiosity while others observe the rest of their surroundings. Here, the story is focused on the innocence and lives of the young Libyan girls: nothing more, nothing less.

Western media expects us to feel sympathy and pity when we see humans that live in a war-torn environment. There’s an automatic assumption that minorities are helpless and uneducated, unable to escape their conditions by themselves and on their own terms. To counter this misconception, Middle East Archive collects photographs that are frank and forthright.

There is no intention of impressing the audience with a cinematic image of non-Western disputes — it’s a raw capture of the Middle Eastern human experience. There is no filter to sugarcoat the prevalent violence in certain areas. However, there is also no filter sensationalizing the entirety of the Middle East as violent. There is no focus on restricting the perceptions of the Middle East to a single mindset or religion.

There are some parts of the Middle East that are experiencing violence and war. It’s good that humanitarian aid is encouraged. But, usually in cases like these, the West is praised for supposedly saving disenfranchised communities. It’s not that minorities don’t know how to speak and provide for themselves. It’s that their homelands have been stripped of the everyday resources needed to provide a safe atmosphere for their families. It’s critical to understand that certain political and economic setbacks don’t encapsulate one’s cultural and personal identities.

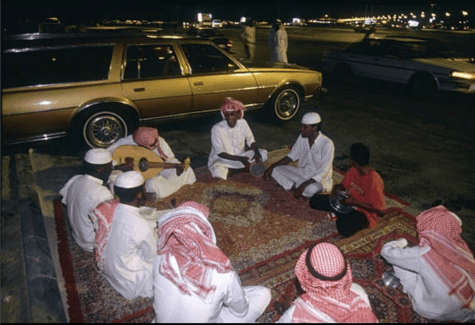

These photographs ask the audience to ponder the human aspects of Middle Eastern life that are usually hidden from the media and to possibly find personal connections with these photographs. This allows the audience to wonder what specific game these two children in Yemen in 2007 were playing and what song these Arab men in Saudi Arabia in 1990 are playing, rather than the narratives of civil strife and disorder that the media fixates on.

Amid the dehumanizing violence in certain regions of the Middle East, there is a desire to authentically embrace a rich cultural background. By countering misconceptions of Middle Eastern cultures, Middle East Archive focuses on cultural appreciation rather than manipulation. The children and families in the photographs are simply experiencing everyday life. The archive is physical proof that, even through calamity, the determination to academically, authentically and respectfully excel has been and always will be present in the Middle East.

Contact Afnan Abbassi at [email protected].