Rewriting the narrative: Conversations on decolonization in art

Contributing writer Sade Collier considers/explores what decolonization means for Black artists.

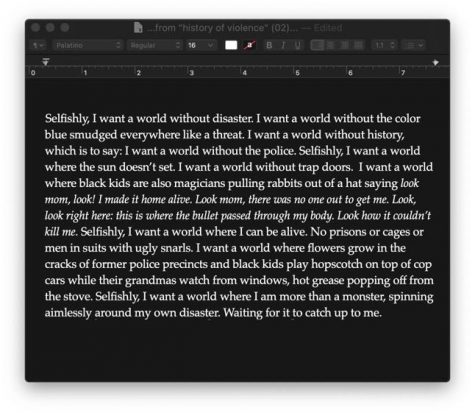

First-year Gallatin student Ian Partman. Decolonization in art as a conversation. (Image courtesy of Ian Partman)

May 3, 2021

INTRODUCTION

Against an orange oak-tinted backdrop, a Black revolutionary holds up a newspaper bearing a blunt message: “ALL POWER TO THE PEOPLE.” There is a shout coming from their mouth and a weapon behind their back. This image is one of urgency and cause, reflective of and rooted in the symbolism of the Black Panther Party.

This artwork was created by Emory Douglas, a revolutionary artist and minister of culture for the Black Panther Party, a political organization founded by Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton in 1966. The Black Panthers operated as a socialist militant group, seeking equality through armed resistance. Here, Douglas uses the visual power of art to portray a particularly imminent sentiment that has penetrated through time: the Black voice cannot be silenced.

Black artists have long used art as a tool for liberation, a mechanism to lift Black people from the depths of oppression and the plague of whiteness. Art is a way to establish a personalized identity of the Black community and a medium through which the Black experience can be expressed in all of its multitudes. It is inherently anti-oppressive because it is joyful, emotional and expressive, untouched by the apathetic inflictions carried by oppression.

In the same breath that art can counter oppression, it can also be a medium to understand decolonization. Decolonization in this context incorporates deconstructing the colonial ideologies of deprivation imposed by the Western world. When applied to art, this raises the question of how the art world excludes minority voices from the canon. It pushes us to examine the ways in which non-white art is often reduced. Through a contemporary lens, art is both a normative template for dismantling systems of oppression and a means of understanding Black culture through its inherently musical nature. At NYU, Black students embody the spirits of artists who came before them, using artistic expression as a mouthpiece for their individual and collective experiences.

BLACK AS BLACK

In his poem “Black Erasure,” Kyle Carrero Lopez writes against the interchangeability assumed between the terms “Black” and “POC” (people of color). Through purportedly progressive language, we have dangerously conflated the two — thus, in socioeconomic, political, academic and artistic conversations, the Black experience becomes generalized into the POC experience. White people are often convinced that using “POC” instead of “Black” is less offensive, a disposition that claims for white people the agency to curate what is considered to be socially moral language. The idea in white America that Blackness has to be continuously diversified ― becoming watered-down in the fixed parallels curated by whiteness — is an exercise in simplifying the Black experience and making Blackness more palatable. Through this so -called diversifying language, white people have decentralized Blackness in its own realm. This conflation has contributed to the neglect and invalidation of the essence of the Black experience, harming the portrayal of the Black image in art and removing the specificity of identity in the Black artist.

“I think [there is a] misconception blatant in the term ‘BIPOC,’” Liberal Studies first-year Ian Partman said. “That there is something that is generalizable about the categories we all exist in, that our art is all reducible to the same thing: that it’s just not white art.”

This misconception noted by Partman is an institutionalized and intentional limitation on Black art and the Black artistic psyche. It is drawn from the same response white people often have to hate crimes, police brutality and other injustices done to marginalized communities. Instead of naming an experience as a Black or Indigenous or Asian or Latinx one, it becomes a POC one. The limitation is based in the avoidance of naming something as it is. This avoidance catalyzes an absolvement from accountability and, in the art world, an absolvement from rightful appreciation, paving the way for appropriation.

Partman also alluded to the imposition of grouping together what is simply not “white art” within the Black community. Often, it is assumed that Black art can only exist under the umbrella of solely Black art, that there are no spokes to the wheel of a Black person’s existence. That all Black art falls into a monolith, and that all Black art is saying the same thing.

“People forget that I am an individual,” Mella LaFrance, a third-year Film and TV student at Tisch said. “When I say something—and maybe I’ll say something super out of pocket — I’m not talking about every Black woman. [A] misconception is that all Black artists speak for other Black artists.”

When speaking of decolonization, we are also speaking of radical differentiation. This means that there is no monolith among Black people, and that Black people do not have to be diversified to be spoken of or to exist. Here, Partman and LaFrance both acknowledge that at the heart of Black art is a communal experience. Yet such an experience is clouded by the assumption that it must be experienced or portrayed in the same way. This imposition is a lazy and imperialist one, as it erases the myriad of stories inherent to and separate from the Black experience.

The needle in the pore of colonization is dichotomization or conflation without agency. Reluctance in allowing Black people to contextualize their own experiences separates the person from their interiority, the person from the community, and the community from the world. It is ahistorical to not understand colonialism as an endeavor of stealing, not merely in a materialistic sense, but also in a soulful sense. It operates in such a manner because Eurocentric hegemony could not exist without forced conformity.

There is an ongoing process of unlearning in Black communities ― unlearning imperialism and the imposition of the monolith. Black art in such a sense can almost be regarded for its objectivity, of revealing a rewritten canon, one inclusive of the Black story. Imperialist thought does not function alongside inclusion because it can only stabilize itself by discouraging the latter. Thus, indulgence in Black art must come with a radical understanding that it exists on an undefinable spectrum, alongside the Black artist.

KEEPING IT REAL

Writing, for Partman, has been a perpetual ascension toward examining the world.

“Art gives us a way of looking into the world,” he said. “If I’m organizing for a world that I want, writing is how I get to thinking about what that world looks like.”

This approach is common in the arts, but often unrecognized. In societies founded on the values of capitalism, art is invalidated as a vocation, pushing creatives to remove themselves from work and pursue what is deemed “real” or marketable. The issue seen in art is that it cannot always be monetized, and for this reason, it is demonized. It also cannot be controlled or fixed, as it is always in the process of being molded as though it were wet flour. Through conjuring comprehensive depictions of society, the arts have revealed the intricacies of the world that are hidden in its crevices.

“Art is the best way for people to hear and understand what’s going on,” Tisch first-year Justin Walton, who performs as hip-hop artist Jwalt, said. “People like listening to music. If you put that in music, sprinkle some of the stuff that’s going on, people are gonna listen to that and listen to what’s going on.”

Political commentary has often been vocalized through hip-hop culture, giving artists the foundation to craft relevance not merely through their artistic genius and personas, but also through the consciousness of their words. Artists such as Common, 2Pac and Kendrick Lamar have encapsulated a generational experience through their work and have been recognized for both their lyricism and radical objectivity.

“Hip-hop came from a place where people were trying to talk about what was going on in their communities,” Jwalt continued, “It’s for people to talk their truth, for people to talk about realness.”

There is a necessity, though, in understanding when to make a distinction between the art and the artist. Imperialist thought has made the Black body into an inherently political one. Through art, this functions as though it were a disease.

“I don’t like to think of the relationship between my identity as an artist and my identity as an organizer as complimentary,” Partman said. “I like boots — cowboy boots. I like jazz music. These are aspects of my identity that are not reducible, even if they are tangential to or parallel to my Blackness. The problem with the conflation between art and identity is that it wants us to not recognize our wholeness. It wants us to not give care to our wholeness.”

Like Partman, Jwalt wants to be a well-rounded Black artist, and part of that means that his art will be about celebration instead of politics and identities.

“People used to call me a conscious artist, and I used to hate that,” Jwalt said. “I was like,

‘Yeah, I can make political music and I can talk about what’s going on, but I also like to make music that makes people happy or wanna dance or have fun.’”

LaFrance, on the other hand, accepts that there will always be a political element to their work.

“Any Black person doing anything is revolutionary, right?” LaFrance said. “I think everything is political, or ideological … I think two truths can exist at once, and I think that, via my Blackness, I am political.”

It is a privilege to not have to have this conversation with oneself or one’s viewership. The debate of separation and its degrees among Black artists and their audiences is perhaps more thorough, given the white assumption that Black art is inherently political, while there are Black artists who have no intentions of creating political Black art. Such a topic delves into a question of privilege and removal and begs us to engage in the politics of applicability.

To simplify the argument, LaFrance punctured it with a decent sentiment: “I don’t know. Read the artist’s statement.”

DISMANTLING THE WHITE GAZE

The interview is well-known and loved. Toni Morrison, in all of her glory, gray-haired and wise-eyed, dismisses the question of white inclusion posed by Jana Wendt with a rhetorical question: “You can’t understand how powerfully racist that question is, can you?”

With whiteness comes the infliction of conventionality — in order to harbor the element of conventionality, one has to wear whiteness like a glove. This is because conventionality in the contemporary world is a concept introduced by Eurocentric standards. Conventionality is tangential to the status quo, but it is not always the status quo. In conversation, we often approach the topic of conventionality as though it exists on a spectrum, rather than assuming that there is a simple way to measure conventionality. Thus, we often applaud art for not being conventional, but this often means that the art is simply less proximal to whiteness. When an unconventional work of art is applauded, it is often applauded for its distance from the status quo rather than its intrinsic worth.

“White America has changed the narrative of what hip-hop is and what it sounds like,” Jwalt said. “In reality, it came from people just wanting to express themselves. For people to talk about what’s going on in their communities, what’s going on in the neighborhood.”

White people have certainly changed the narrative, and not just of hip-hop. In changing it, they’ve gentrified it. Musical gentrification is a rather new concept in the mainstream, although it has been happening for decades. Plenty of people are familiar with the song “Hound Dog,” seemingly written by Elvis Presley, but in truth only popularized by him. They are not familiar with Big Mama Thornton, the Black blues singer who first recorded the song in 1952. The music industry in America, so often fueled by the Black community, so often strips it of its authenticity.

Artists like Jwalt are working through that. “[My art] is authentic,” Jwalt said. “It’s me. It’s true. In no way in my art do I feel like I’m trying to censor myself and adapt to what colonialism is or try to make my music fit into that.”

LaFrance also denounced the assumption that Black art should be created with proximity to whiteness.

“All of my art is to figure out myself, because I like what I do,” they said. “ I feel like a lot of it feels like it’s for a white audience, [but] I didn’t make this with a white audience in mind. I made this in mind based on how I feel in the moment.”

This here is also often a lesson of unlearning for Black artists. Imagine spending your entire upbringing learning exclusively of white authors: Emily Dickinson, Sylvia Plath, Shakespeare, Walt Whitman and Charles Dickinson as staples — but not touching the works of Toni Morrison, Maya Angelou, Zora Neale Hurston, James Baldwin or Ralph Ellison until your adult years. This is why the canon is questioned as to whom it allows within its walls.

Then how do Black artists get a seat at the table?

“Representation is a trap,” Partman said. “It forces us not to aspire towards freedom, but to aspire towards the recognition of humanity.”

If we are bound to only being represented, we are bound to conceding to what should already be implied. The white gaze chirps and asks the Black artist why there is no inclusion beneath the Black pen. The Black artist, though, does not see an avoidance of writing about the white experience or painting the white experience as an act of exclusion. It is the act of redefining, for the Black community, an experience so often left out of the canon, an experience that is neglected and criticized. The insistence that the reasoning for Black artists’ negligence of the white experience must be explicitly revealed is a racist one that, as stated by Toni Morrison, would never be asked of a white artist.

ART AS LIBERATION and VOICES AS SURVIVAL

As a child, Partman often used writing as a mode of communication rather than speaking. Now, he ses writing to comb through the thick strings of the sociopolitical sphere.

“I’ve been thinking a lot about political depression, and how when we have all of these tools and ways of material organizing, that feel somehow still inadequate, what do you turn to?” he asked. “What I turned to personally was writing. Writing gave me a sense of clarity.”

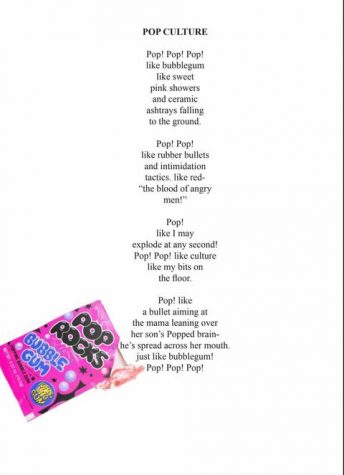

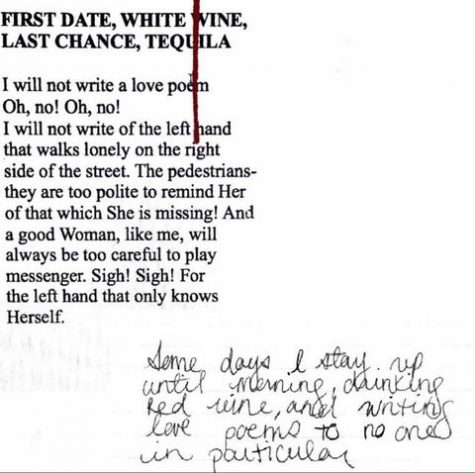

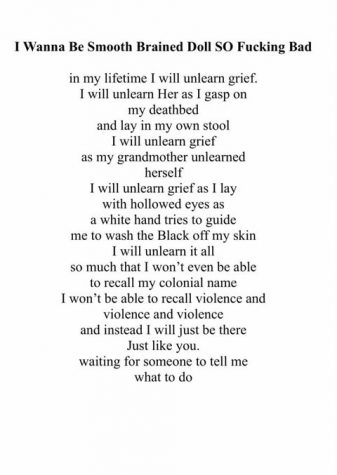

Through writing, so many other Black creators have found this sense of clarity. It is knowingly cathartic to write, to be expressive on the page. Numerous Black writers have found generational healing by rewriting the narrative — Morgan Parker’s contemporary poetry collection “Magical Negro,” for example, brushes through the ancestral reigns of Blackness in a way both mystical and troubling. Writing has given birth to tangible thoughts through the quill and the ink, allowing Black people to communicate what they could not quite verbalize. It also alludes to the immense amount of radical resources that are available through text. Writing is full of an ancestral and radical mysticism. We speak of artists such as Spike Lee, Audre Lorde and Kara Walker as providing us with toolkits conducive to expressing the Black experience. When there were no vocalized words to produce what we were feeling, we turned to writing as an art.

Writing can be a healing mechanism. When speaking to LaFrance, she coined the beautiful phrase meaningful rage, in a conversation on trauma and the ways in which expression through art can help one heal. She also touched on art as survival.

“Some people are in [art] school because they can be, and some people are in school because they use art to survive.”

This, though, is not a practice of gatekeeping. It is a practice of recognizing how often Black people have turned to art when their voices were not heard. How often Black people told their stories through art.

“It gave me another voice,” Jwalt said. “It gave me another voice to express myself. It gave me another platform to let go. For so long, I felt like my voice wasn’t valid.”

For years, Black people have existed in a climate that ignored their voices, their sounds, their art, their writing. In searching for validity, we find that meaningful rage. There is an urge to tell a story so often stomped on alongside the weeds. The story, here, is one that exists with its hands aching toward liberation.

“There is actually something incredibly liberating about the act of disappearance and the act of mortality,” Partman said. He began to beautifully recount a scene in the 1989 short film “Looking for Langston,” a movie centered around the life story of Langston Hughes. Partman criticized the necessity of imperialistic art to be immortalized, speaking of this hunger as a futile attempt to counter “noticeable imperial decline.” Immortalization, through Partman’s analysis, is nauseating and unfulfilling.

This haunting statement gives rise to another question: what exactly is the Black artist writing toward? Is it to be seen, to be recognized? No. This, as mentioned by Partman, is a question of humanity. We know we are human and deserving — we should not have to ask for visibility. There is something more beautiful, seductive and alluring than writing towards visibility: writing toward the unknown.

There is an understanding in Partman’s words: Black art is impactful through mortality because of its urgent, soulful, loud, joyful and liberating. It survives without imperial greed or materialistic fantasy. It survives separate, not inside or outside, of whiteness. It just is.

Audre Lorde famously wrote that the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. The thing is, Black art must function through this sentiment — where there is Blackness, there must only be what is curated by Blackness for Black people. Black artists are not writing on the foundation of whiteness. Black artists are not working to build a foundation that excludes whiteness. They are working to build a space, a communal space, in which the Black person and the Black art will not be commodified or claimed. The foundation creates the monolith and fuels the conventionality. The foundation is imperial.

There has to be the continuation of Black art through some means, some outlet to further the legacy.

“We’re gonna have to keep on creating for people to see that what we’re doing is art,” Jwalt said. “This is real art.”

Decolonization begins not by writing against or separate from whiteness, but writing without it plaguing the mind. Decolonization is a radical unlearning process, something that begins within. Once the institutions fall, these implanted ideologies that hinder the furthering of Black art still remain. We have no other choice but to write past it.

“How do we immortalize [art]?” LaFrance said. “Revolution.”

Email Sade Collier at [email protected]