‘Oklahoma City’ Proves Depressingly Relevant

Courtesy of American Experience Films

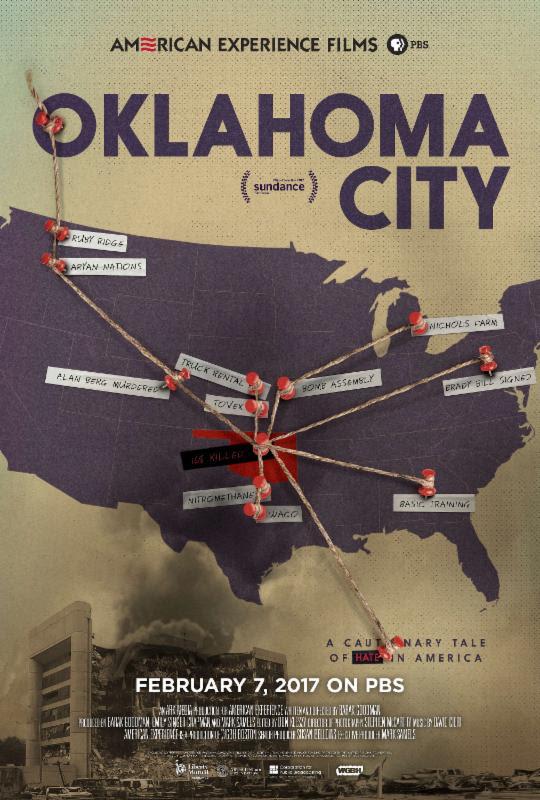

Barak Goodman’s new documentary, “Oklahoma City”, recounts the Timothy McVeigh’s bombing of a federal building in 1995.

February 6, 2017

A federal building was destroyed by a bomb in 1995 in Oklahoma City, OK and the town itself was left shaken. White supremacy, restrictive gun laws and anti-government sentiments were all motivators for bomber Timothy McVeigh. The act of violence was one of the worst instances of domestic terrorism in U.S. history and disturbed citizens nationwide. “Oklahoma City,” Barak Goodman’s new documentary, recounts the shock of McVeigh’s attack and traces back all the details surrounding the man’s extremist beliefs. It’s a riveting humanization of a domestic terrorist, and the film itself frighteningly echoes tensions that are prevalent today.

Although McVeigh became a terrorist who murdered 168 people, viewers learn that in his youth he was a shy introvert with no police record. In documenting his adolescent years, the film takes the audience on a journey through the process of McVeigh’s radicalization. As a child, he was bullied and developed a hatred for his attackers.

Later, McVeigh joined the U.S. Army since he couldn’t figure out which career to pursue – he thought he would enjoy it because of his affinity for guns. Although he excelled in marksmanship during training, he became quickly disillusioned once deployed to Kuwait. The documentary highlights this as a critical moment in McVeigh’s life. He had no purpose until he joined the Army — but once deployed, he couldn’t understand why he was there. His Army years were a formative period in which McVeigh began to see the U.S. government as a ruthless bully rather than a protector.

The film goes on to examine two historical events that influenced McVeigh. One was the death of white supremacist Randy Weaver, who had led a secluded life in the forest with his family. Weaver’s purchases of several black-market firearms with other white supremacists led the government to arrest him and his family, which ended in a shootout and the family’s deaths. Soon after, in Waco, TX, a cult was raided by the police this resulted in the deaths of cult members and U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms officers.

Although the cult leader himself ordered their shelter to be burned down to avoid arrest, McVeigh believed the government’s actions were unwarranted. Following the Waco massacre, his anti-government stance grew stronger, culminating in the burning hatred that led to his attack in Oklahoma City.

Considering the current climate of American politics, it is hard not to notice the ideals of McVeigh in the actions of Trump and his supporters. White supremacy and anti-government zeal isn’t a new idea, nor have these principles been relegated to the past. By showing McVeigh as a real human and giving his past a story, it is much more difficult to write off his actions — and the attitudes of others like him — as the work of the mentally ill. This intense and complex documentary is not only troubling because it shows the lives of white supremacists and other extremists, but because of the resurgence of white supremacist movements in America today. With a president whose own actions have some citizens noticing the similarities to white supremacist theories, the documentary is even more disturbing.

A version of this article appeared in the Monday, Feb. 6 print edition. Email Sophie Bennett at [email protected].