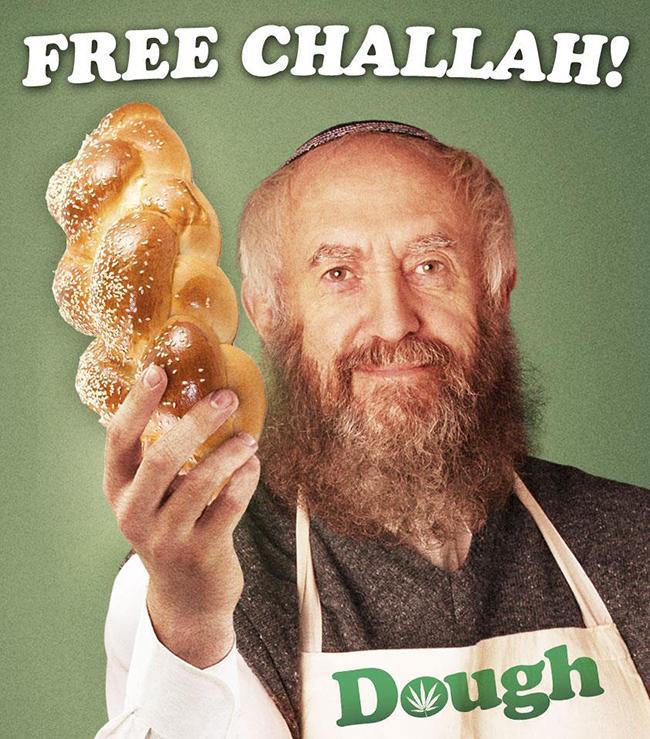

‘Dough:’ Baked in Two Ways

“Dough” follows the life of Nat as his bakery and drug dealing cross paths.

April 25, 2016

Since religious practices and familial rituals usually occur in the same sphere, blurring the distinction between the two entities becomes a matter of course. When a diametrically opposed viewpoint is introduced, those lines become distinguishable, establishing boundaries once more. This nuanced dynamic is the center of John Goldschmidt’s “Dough,” a quietly charming but tonally inconsistent film.

The film documents the life and times of Nat (Jonathan Pryce, the High Sparrow on “Game of Thrones”), a Jewish man in charge of his family’s London bakery that has been passed down from generation to generation. The business is in dire straits, as Nat tells one of his few remaining regular customers that his former frequent patrons are either moving out of London or dying.

Nat takes a chance on hiring his cleaning lady’s son, Ayyash (Jerome Holder). Ayyash, though depicted as an irresponsible young man in pursuit of a steady wage, has a dark past and a foreboding present. A refugee from Darfur abandoned by his father, he has resorted to a life of drug dealing, requiring a “cover job” to continue working for his brutish overseer Victor (Ian Hart). These paths cross when Ayyash begins infusing his marijuana into the goods at the bakery, completely reinvigorating Nat’s business.

While intriguing, there are far too many elemental inconsistencies that prevent “Dough” from being a holistic success. Goldschmidt, as well as writers Jez Freedman and Jonathan Benson, attempt to tackle numerous systemic issues without the intersectional execution to do so. The themes of familial tradition, religious differences and the attempted reconciliation of such ideological grievances, are presented superficially without ever reaching any point of closure or satisfaction.

The film’s most poignant scenes involve constructed parallels. Consider a scene between Nat and Ayyash: Goldschmidt presents a simultaneous shot of the two men praying before opening the bakery. Nat, donning Jewish garb and holding a necklace close to his face, mutters incantatory words directed towards God. Ayyash lays a prayer mat on the ground, praying to Allah. Both men are summoning the same feelings and outcomes assigned to opposed doctrines, and yet that mutuality of faith does not present itself as an opening for empathy between the two. Nat warms up to Ayyash eventually, but begins in this instance by telling him to pray somewhere else where nobody can see him.

Powerful contentions like these get lost in the disorganization of the second half of the film. Due to this disarray, “Dough” eventually falls flat. Overall, the film is conceptually successful at raising thoughtful arguments about faith and tradition. Unfortunately, proposing such topics for discourse is all the film manages to do, failing to tie these thematic elements together to deliver any semblance of a clear, resounding message.

“Dough” will be released in area theaters on April 29.

A version of this article appeared in the Monday, April 25 print edition. Email Bradley Alsop at [email protected].