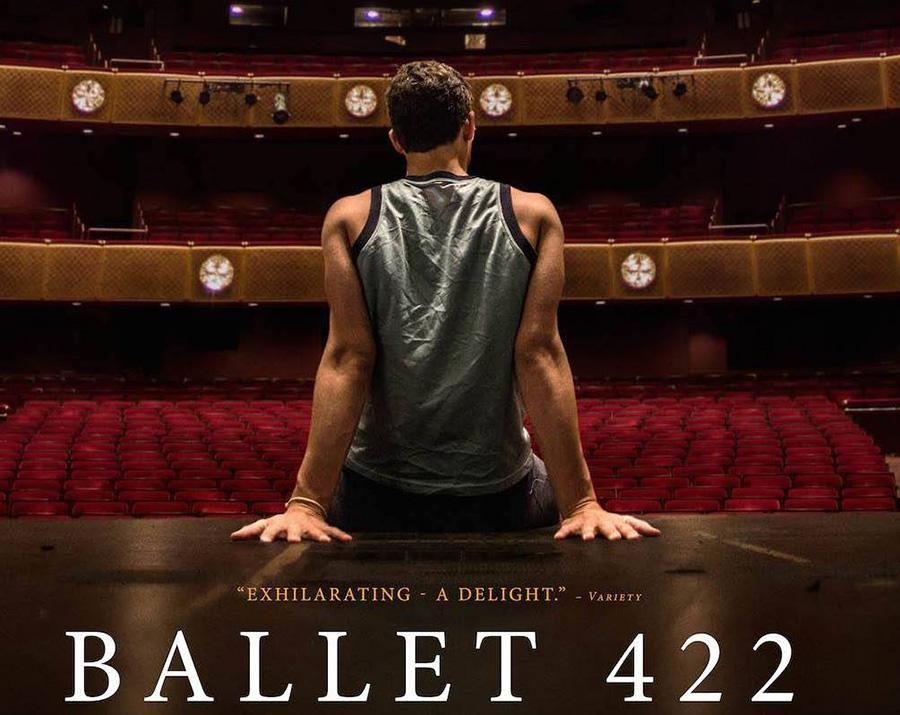

Alum pulls back curtain on ballet

Jody Lee Lipes’ “Balley 422” follows Justin Peck’s creative process as he builds his troupe’s show.

February 3, 2015

Jody Lee Lipes’ newest film “Ballet 422” is hypnotizing and inclusive as it guides its viewer behind the scenes of the revered New York City Ballet. The film is elegant and majestic like the subject it portrays, giving a more distinguished quality to the art of ballet. Shot in cinema vérité style, which means it was captured without the use of interviews or voice-over, but as a constant flow of process, this documentary shadows the 25-year-old New York City Ballet performer Justin Peck as he faces the challenge of creating the illustrious company’s 422nd ballet.

Lipes graduated from Tisch School of the Arts in 2004, and he credits his education there for the production of “Ballet 422.”

“I would not have been able to make this film without going to NYU,” he said. “Many people who worked on this film, I met at NYU. Nick Bentgen, Anna Rose Holmer, Mark Phillips, Joe Anderson and I all met while attending Tisch.”

Lipes first conceived the documentary, after he and his wife went to see Peck’s second ballet, “Year of the Rabbit.”

“After that, we began talking about documenting his next piece, because I knew one day he would become an important choreographer,” Lipes said. “I just know I would have loved to see what renowned choreographers were like earlier on in their careers.”

Peck is quiet and contemplative in his planning; the gears of his mind are perpetually working to make improvements to his ensemble. He never looks directly at the camera or acknowledges its presence. Like a fly on the wall, we see him but he never sees us.

“The subject matter definitely required [cinema vérité], because ballet is such a physical art form,” Lipes said. “I loved how it was active and able to communicate without people having to talk. With vérité, it’s also like a ticking clock, so I also enjoy the style because you’re able to be physical while having a timeline

for structure.”

Lipes, who became instantly immersed in the world of the New York City Ballet, followed his subject everywhere. The audience glimpses the entire process of creating a ballet ensemble. From costume design fittings to conversations with the orchestra, Peck controls every aspect of his piece to the best of his ability.

“Most people don’t understand the inner working and mechanics of the institution,” Lipes said. “A lot of people outside of the production never think about how many people go into the process, the intricacies, and the costumes. The orchestra, particularly in ballet, is overlooked a lot as a creative partner in a ballet; the audience doesn’t usually think about its

importance to the piece.”

While creating this new piece, Peck also had to fulfill his role as a dancer in the Corps de Ballet. As soon as the curtains opened on the New York City Ballet’s 422nd production, his responsibility as choreographer came to an end and he once again became a dancer. Like a chameleon, a jack of all-trades, he eases right back into his

home onstage.

The film is a subtle portrayal of metamorphosis. Lipes follows Peck’s transformation from beginning to end, as his subject becomes a quiet-yet-masterful butterfly taking on the challenging waters of the New York City Ballet.

A version of this article appeared in the Tuesday, Feb. 3 print edition. Email Sidney Butler at [email protected].