Deep Red, Chapter 1

Part one of a pulpy whodunit in the fictional town of Coleridge that brings a green detective to a rotten scene.

April 1, 2020

Coleridge is a small town. It used to be a factory town, and it felt in those days like the grandparents whose best stories are decades old. Now, it feels like the grandparent lost to dementia, forgotten of everything.

Because of how small the town was, when the blood was first found it rocked the whole system, from the town’s skateboarders to its police officers — a group I had luckily just joined in time for the party, I suppose. When it happened, I was in my first few years on the job.

Coleridge only has one car wash in its borders, but most people tend to head to the one in Rockport, a ways east, after what happened.

At Coleridge’s only car wash, Lenny’s Drive Thru — there was no Lenny, his name was Jeff — someone had left quite the scene. Because of the town’s size, Lenny’s Drive Thru was just a series of two or three brick stations, sort of like a bus stop for a car. People would park underneath the shielding, get out, grab a hose on the wall and wash down their own cars. Jeff had one of those toll booth stations installed in front of the buildings, so he could charge, direct and oversee from his little booth.

Well, would oversee unless he was sick. Or tired. Or drunk. It was his business, and in his defense, Coleridge wasn’t a town known for people protectively watching their stuff.

To cut the cord already, someone came into Lenny’s Drive Thru one night in a car that had been at the scene of a grisly murder. The reason we knew was because at each of these stations, the floors were slightly banked towards drains in the center. However on this occasion, that drain had been clogged with a lot of blood, and a lot of hair. The drain clogged, the blood kept coming in and what was left after the car drove off was a pool. Suffice to say, the woman who found the scene is still in therapy.

This was all at 2:30 in the morning. I mean hell, he could’ve done it at 4 p.m. and there probably wouldn’t have been witnesses, but we found out it had to have been around 2:30 a.m. because Linda Carol had been woken up by the sound of the hose turning on.

Her house was just behind Lenny’s, and her bedroom window faced the wash. She told us her bedroom window had to be open every night because otherwise it got too humid in her room. She would wake up to every car coming in. Luckily, cars didn’t come often.

That night, the murder car was the only one who came through, according to Linda. She also told us that the car made a very loud, rhythmic clicking sound. Her husband chimed in at this point in the interview, from the living room, to yell that it meant the muffler was broken. And with that, the case stopped being a mystery and started being a race.

Who would be the first officer to call the lucky mechanic that fixed a muffler, who would find it?

At that time it felt like playing a board game. Being a cop in that town sort of felt like living on a clue board where everyone refused to move, and you just had to wait, constantly hoping it would be your turn someday. Once there was a game to play, I pulled all-nighters when I thought it would get me closer. Many calls later — surprisingly, one car wash, but 28 mechanics, just in Coleridge — I found the mechanic. And it didn’t even turn out to be Coleridge, he had gone out to Point Scope for the job. He must’ve thought it was far enough.

We got lucky with this case in that he hadn’t expected or caught the drain clogging. If he had, I believe to this day that he would’ve planned enough to escape. But he thought he was in the clear — no evidence, no questions.

Vinny’s Auto Works repaired a muffler that had been causing the clicking sounds that matched Linda’s description perfectly. When I found out, I knew it was him when Vinny (this time, there actually was a Vinny) told me this repair had been different. Due to what the client called an unusual work schedule, he left the car in the parking lot overnight with cash in the glove compartment. When the car was repaired the client told Vinny to leave the car in the same spot, and he’d pick it up overnight. Vinny never saw this guy’s face, never met him. That was just too convenient.

The car was registered to Todd Reynolds, a 23-year old college dropout who had majored in criminal justice until flunking out. The car was a gift from Todd’s grandmother, who he lived with. When we took him in, Todd was hysterical, telling us the car had been stolen weeks ago but that he was too scared to tell his grandmother because she had enough on her plate. She was sick and he told us he thought the news would kill her.

Was I supposed to believe him?

Over the four and a half hour interview, Todd took me through his life story, begging me to realize he was just a little kid who didn’t do anything wrong. He talked about the day his grandmother told him he was old enough to know that his parents died in a car crash. He told me about the day he was older, old enough now to know that they hadn’t, but had instead left him as a baby on her doorstep, and disappeared forever. He told me about his grandmother’s cancer. He told me that the last thing he wanted was to hurt people. I left him to stir a while.

Then Vinny sent over the footage from those two nights in his parking lot, and the posture of the figure in the video matched so well with the man in the interrogation room. The evidence was stacked against him, now in more ways than one.

I combed for the security tapes of the entire town — any homes and businesses that gave us access to their archives. Because there weren’t many homes nor businesses in Coleridge, we had access to most footage, save a protective neighbor or two’s. I looked for the green CR-V for almost a week. I found no footage of the car. This supported Todd’s story: if the car had just been stolen its thief wouldn’t want it back in view quickly. That created a shadow of doubt in my mind that has never left.

With the video and registration as probable cause, I decided, even though it was not a sure thing he was involved, to search his home. It would alert his grandmother and likely give Todd a lifelong hatred of the Coleridge Police Department, but I told myself that if he was innocent, we wouldn’t find anything.

I remember the day well. I told myself not to be worried, because by this point I believed Todd, and a part of me knew him to be innocent. Or at least, wanted him to be innocent.

I had a long talk with Todd in the squad car outside his home, waiting for the team to finish the search. In the car, I told him that I was so sorry to do this to him, but I knew he was innocent, and that this was the quickest way to prove it; he would forget about this in a month.

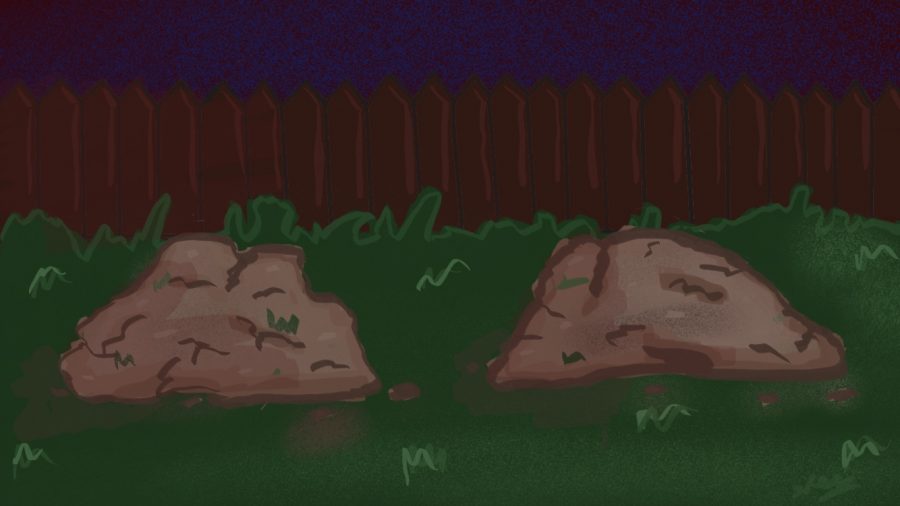

Moments later, my partner came outside and told me they found a shallow grave behind the bushes, just in front of the fence-line. Up to this point we didn’t know how many bodies we were looking for, or if there would even be bodies.

We searched his house for a hypothetical murder weapon, we didn’t expect remains at all. All we could determine from what was left in the puddle along the drain was A-positive and AB-negative blood. Two blood types often means the blood of the victim and the killer in a struggle.

Instead, we found Robert and Samantha Flier buried together in Todd’s grandmother’s backyard.

Email Matthew Davis at [email protected].