A year ago, around this time, I was wandering the streets of Shanghai.

Growing up Peruvian and learning about the huge influence Chinese immigrants had on Peruvian culture dating back to the 1800’s, especially Peruvian cuisine (for proof, chifa), always fascinated me. Just like this, my curiosity pushed me to find a way to fit a study-abroad semester in China into my tight academic plan. With no previous knowledge of Mandarin, I found myself struggling to communicate outside the walls of English-speaking NYU Shanghai. It was nerve-wracking not being able to read or write or speak, abilities I had taken for granted since I was a kid. Fortunately for me, Shanghai is a major city so many people knew English to some extent. But misunderstandings would occur all the time regardless, especially in the mom-and-pop restaurants, so I would often rely on my Mandarin-speaking friends to convey my thoughts.

My frustration of not being able to learn Mandarin fast enough despite taking language classes four times a week kept growing. I thought I had made the wrong decision going to China. But after long hours thinking that there was no way back, I realized that I didn’t need words to feel, learn and enjoy. My camera lens became my voice and allowed me to share memorable glances and smiles with the locals and the city. I became a flâneur photographer on a mission: “an armed version of the solitary walker reconnoitering, stalking, cruising the urban inferno,” as Susan Sontag described in her essay “On Photography.”

I never stopped being a foreigner but I felt more comfortable living in China by the end of the semester. I was a wanderer who was okay with missing a subway stop just to see a new station, a wanderer who was okay with mispronouncing food names in Mandarin and getting the wrong order just to try a new dish, a wanderer who was okay with walking for 40 minutes from my dorm to the Huangpu River just to discover new sights on the way. As I adopted the flâneur mindset, a whole new city was unveiled in front of me, and I became more and more familiar with it every day. Without trying, I added new words to my lexicon and got a better sense of direction around the city. Four months fell short to explore Shanghai at its fullest.

Early this year, I decided I wanted to go back to China and had a million travel ideas, but everything vanished when the coronavirus entered the picture. As news of city-wide quarantines and deaths flooded the internet, I found myself looking at my photos of China more and more often, wondering what had happened to my subjects and the places I visited.

I wonder if they are okay. I don’t know.

The images of empty streets, dying patients and health workers in astronaut-like suits flooding the media don’t resemble the country I remember at all. The camera, the tool I used to connect with China, is being used to sensationalize the epidemic, leading to dangerous stereotypes and racism against Asians worldwide. Although the Chinese official death toll decreased recently, no one knows how long it will take for businesses to reopen, for children to begin attending school and for people to get their health back. No one knows how long it will take for xenophobes to stop accusing every Asian of having the virus.

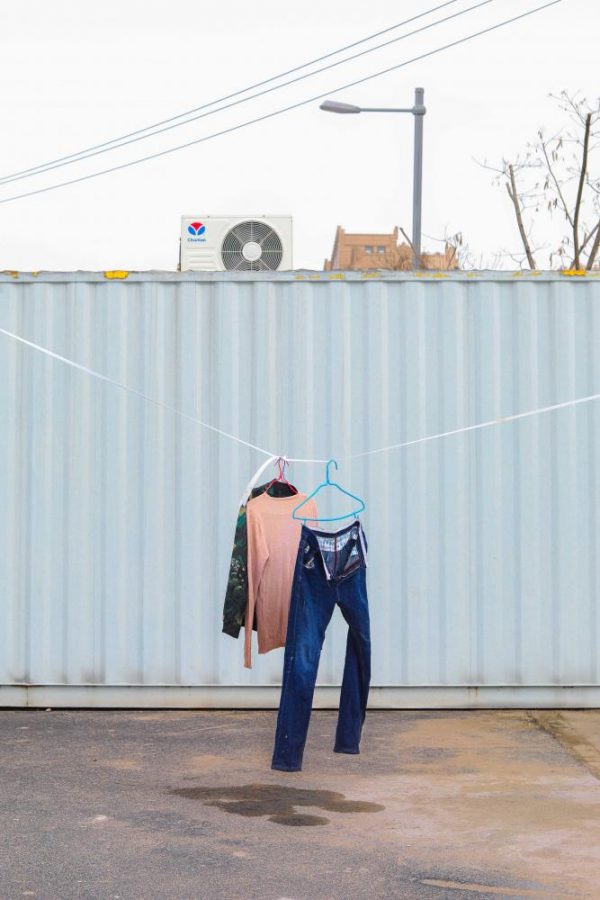

And yet, in the midst of this uncertainty, I have my photographs to remember Shanghai and its people. This selection of photos encapsulates my time as a deliberately aimless pedestrian around Yu Garden, Nanjing Road and Sanmen Road in the spring of 2019. From sophisticated art at the Fosun Foundation Art Center to clothes hanging in the streets, I saw different definitions of what Shanghai really is during my hour-long walks. It is in the contrasts and combinations of colors, of sounds, of people, that Shanghai acquires its unique personality as a city that is extremely global and at the same time, unmistakably Chinese. This is the essence that I hope Shanghai preserves as it tackles the current viral pandemic.

Email Alejandra Arevalo at [email protected].