An Indian Poet Finds the Sublime in the Everyday

By Alex Cullina, Theater & Books Editor

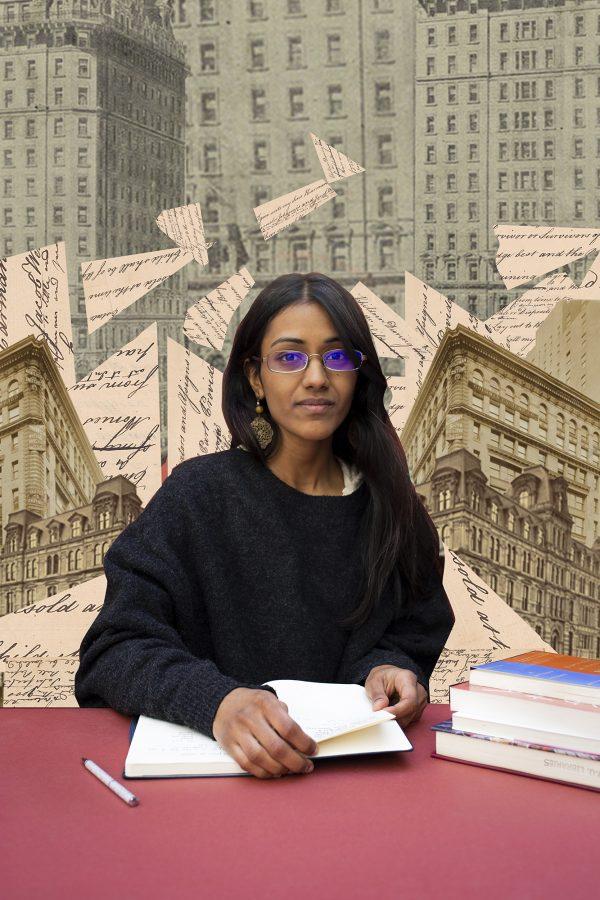

![]() evanshi Khetarpal doesn’t know what kind of writer she wants to be.

evanshi Khetarpal doesn’t know what kind of writer she wants to be.

“My interests are all over the place,” she said. “Writing is a constant, although writing about what and how keeps changing.”

Regardless, the 20-year-old Indian poet already has a resume longer than many professional writers. She has two books under her belt, with a poetry collection set to debut later this spring, not to mention a slew of pieces for online publications. In 2014, she co-founded the literary magazine Inklette; as editor-in-chief, she commands a staff of about 20 volunteers around the world.

When she was 12 years old, Khetarpal published her first book, a young adult novel called “Welcome to Hill Top High” about a young girl’s adventures during her first year of boarding school, through a small local publisher in India and Kids Pub Press in Boston. Now, though, she sometimes wishes she hadn’t.

“I haven’t kept track of that, and I don’t think I want to,” she said about the novel, which she calls “a very horrible one,” with a wry smile.

But by her teenage years, Khetarpal, now a LS sophomore studying Comparative Literature and Creative Writing, had begun taking writing seriously as a career.

Khetarpal grew up in an upper middle class household in Bhopal, a large central Indian city. Her father is a pediatrician who owns a private hospital and her mother is a professor of forensic medicine. Khetarpal started her literary education at an all-girls Catholic convent school. The English literature curriculum at the school, which she attended from kindergarten through high school, was focused heavily on white, colonial-era British writers like Enid Blyton and Rudyard Kipling.

“We never heard that Kipling was the one who basically coined the term ‘white man’s burden,’” she said, “but we would read him, and he would be like this grand figure of literature in our textbooks.”

Although she did read some Indian literature at school, like the work of the great novelist Premchand, overall, she was dissatisfied with the breadth of the curriculum.

“It was kind of very English- and North America-oriented,” she said.

As she delved deeper into work by Indian writers like Premchand and Rabindranath Tagore on her own, she came to appreciate how important it is for Indians to read Indian literature.

“It helps you get in touch with the lives of people around you,” Khetarpal said. “I think in India it’s very easy, especially for a person who’s relatively privileged, or who’s not living in poverty, or who’s not from a lower caste to sort of dismiss those problems.”

Like many Indians, Khetarpal grew up speaking multiple languages. She speaks Hindi with her family, while her education was conducted in English.

“To grow up bilingual is a complex thing to navigate,” she said. “Though I write in English, I kind of feel guilty about writing in English and not in other regional languages sometimes, or Hindi.”

While English was a required subject for every year at her high school, other language study was not; Khetarpal stuck with Hindi through her senior year by choice — she wanted a better understanding of the literature of her first language.

Hindi literature “was just looked down on,” she said. People she knew generally didn’t treat it as seriously as English literature.

“I think because we grew up with a colonial mentality that English is great, and Hindi is not,” Khetarpal said. “It took me a long time to sort of wrap my head around the fact that Hindi is sort of my mother tongue, and always will be.”

To push back against that, she tries to read Hindi literature as well as work that has been translated into Hindi.

As she began to hone her craft, Khetarpal spent her high school summers studying at well-regarded writer’s workshops in the U.S. and U.K., one being the Iowa Young Writers Studio. She’s still in touch with many of the other young writers she met during her summers abroad; some of them are now Inklette staff members.

Khetarpal decided to come to New York City for college so she could participate in the city’s world-renowned literary scene.

“I really love New York,” she said. “If I want something entertaining to do for tomorrow, or the next day, or I want to attend a literary event, something’s going to be going on somewhere.”

Her first taste of New York literature was on the internet, through the online presence of American literary magazines like The Paris Review and The Adroit Journal. This community of writers and readers solidified her goal of becoming a writer and sparked her desire to move to New York.

It was also online where she found contemporary Indian writers she loves, like Akhil Katyal, a poet and translator who promotes his work largely through social media. A major inspiration for her next collection, “Small Talk,” Katyal also wrote the foreword to the book.

Katyal’s work — he writes in both Hindi and in English — is epigrammatic. Many of his poems are barely longer than a tweet. He’s unapologetic in the way he collapses the distance between the personal and the political, or between the broad and the particular — his most recent collection is titled “How Many Countries Does the Indus Cross?”

In “Small Talk,” which Khetarpal wrote during her final two years of high school and her first year of college, she explores similar thematic territory and is correspondingly concise.

“I think it’s pretty clear that in some poems I do talk about national issues, or political issues, or social issues that cause me pain, but I think it turns more into a telling of why I feel pained by them,” she said. “I think they become kind of like, I think, tellings of pain or trauma, in my own voice.”

In the foreword to “Small Talk,” Katyal writes of Khetarpal’s work, “she marries the precise to the ponderous, the small to the sublime.”

Khetarpal opens the poem “Night & Back,” with a direct address: “Kashmir, you are a name / I once had.” She writes about the conflict in Kashmir with explicitly personal, even bodily terms. Expressing how close she feels to it both emotionally and physically, she writes, “The gulmohar falls / on my chest like a stone.”

Almost none of the poems in the book are longer than a page; many are only a few lines. But Khetarpal’s work is nevertheless wide-ranging — she cites Sufi poetry, known for invoking natural elements like snow or rain, as another influence on the collection.

Each poem is crystalline and exact — entire universes of feeling and expression compressed into a dense, compact gem of language. The entirety of “Nomenclature”: “The sun spills / through the seams / of your saree. // The light grows.” Like the best of Khetarpal’s work, it’s simple, declarative and yet profound.

As for her future as a writer, Khetarpal isn’t quite sure what it’ll look like, as she’s writing more essays, experimenting with translating Hindi literature to English and exploring the possibility of writing about her childhood.

The final poem of “Small Talk” is titled “Endnote: June 2018, New York City,” written just after the end of her first year at NYU. It begins, “What if I were to ask if / I could manage it?” It’s safe to say, if she were to ask, the answer would be a resounding “yes.”

Email Alex Cullina at [email protected]. A version of this article appears in the Thursday, April 4, 2019, print edition on Page 10. Read more from Washington Square News’ “Arts Issue Spring 2019.”