Opinion: The precarious path to employment for international students

Job prospects are too narrow for international students, especially those who are pursuing careers within the United States.

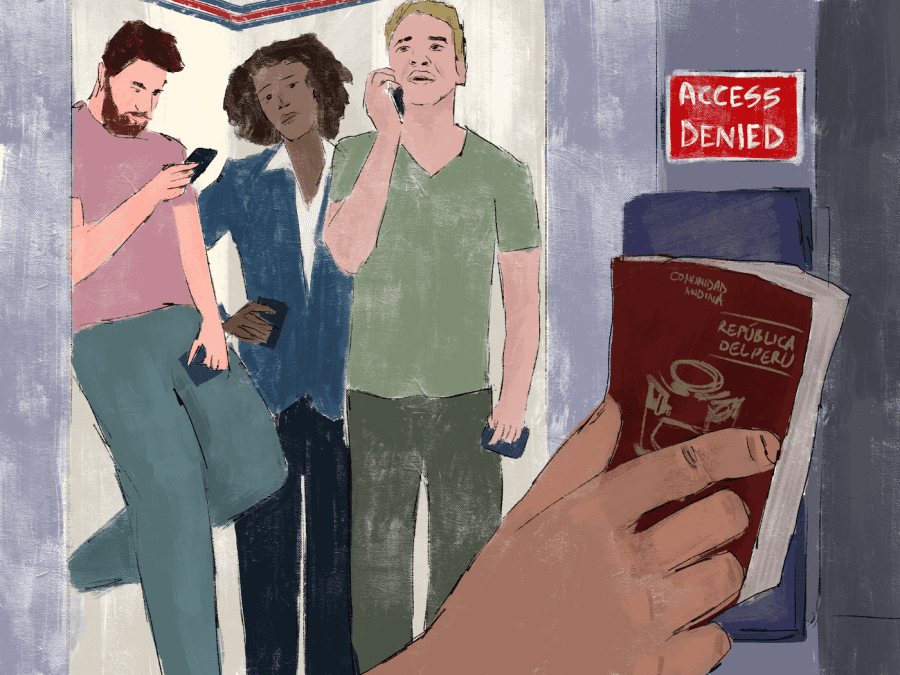

(Illustration by Vedang Lambe)

December 9, 2022

As an international student, coming to study in the United States involves navigating a never-ending obstacle course. You must apply for and attain a student visa. You are restricted to only working on-campus jobs, with some exceptions. Through Optional Practical Training, you are limited to working just one year in the country once you graduate — but three years if your degree is in a STEM-related field.

This is without mentioning the yearly Form I-20 signature request from the Office of Global Services to prove that you still study at the university, or the cold sweats you get every time you have to talk to the immigration officer at the airport.

From the moment you graduate college and start your career in the United States, you know the clock is ticking. The playing field narrows even further when you learn that in order to get a work visa, you must land a job with a company that has enough wealth and the appropriate infrastructure to sponsor the application process. Only then can you enter the lottery for a chance to win yourself an H-1B work visa.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security defines the H-1B visa as a nonimmigrant classification that “applies to people who wish to perform services in a specialty occupation, services of exceptional merit and ability relating to a Department of Defense cooperative research and development project, or services as a fashion model of distinguished merit or ability.”

The most common careers that help people obtain this visa are programmer analyst, business analyst and consultant. Companies in these industries often give out the most internships and offer some of the highest paying entry-level positions. Additionally, they have the infrastructure, including lawyers, funding and support to sponsor international employees.

The H-1B work visa is based on the premise that the United States wants more people to pursue jobs in technical fields. This means that for someone studying politics and journalism, like me, the prospects are dire. (Though for whatever reason, the U.S. government considers NYU’s journalism program a STEM major when it comes to OPT eligibility, which would allow me to remain and work in the U.S. for three years instead of just one.)

Jana Algarañaz, an alum of the Stern School of Business, obtained an H-1B visa on her third OPT year through her job in consulting.

“If you don’t get selected, and you no longer have a visa after that year, or a valid visa, you have to leave the country,” she said.

Other work visas are available for exceptional researchers, artists and people investing large amounts of money in the country.

What does this mean for international students pursuing non-STEM professions? Is it even worth pursuing a career in the United States? Is a non-STEM job somehow less valuable?

With such a slim chance at attaining the visa, students like Alejandra Mejia, who studies fashion at the Fashion Institute of Technology, have even lower chances at finding work.

“When researching for an internship last summer, it was extremely challenging for me because many fashion companies would reject me only because I was an international student,” Mejia said.

Most job applications in the United States require the applicant to disclose whether or not they will need visa sponsorship in the future. When companies see the applicant will need visa sponsorship, the applicant’s chances at the job all but disappear.

“The job process for me as an international student with a non-STEM career has been extremely challenging,” Mejia said. “I feel there’s a lot of pressure, especially wondering if they’re going to give me a work visa or not.”

Even after being selected for the visa, there may be a long, unclear path ahead.

“The whole process just feels uncertain,” Algarañaz said. “It’s not like you’re getting updates throughout the process. There’s a lot of moments of silence where you don’t know how things might be going. And just also the fact that you’re fully dependent on your employer and that your employer is fully in charge of, you know, whether they decide to keep sponsoring you or not.”

There seem to be two outcomes for international students at that point. You can work in a technical field, get an H-1B visa (if you’re lucky) and then be tied to that sponsor for a maximum renewal of six years in total. The other outcome involves finding a company in a non-STEM field that is big enough to have the lawyers and infrastructure to sponsor a visa.

All of this paints a bleak picture, but unfortunately, it’s the reality for international students — uncertainty is a part of our education. We all just should’ve gone to Stern instead.

WSN’s Opinion section strives to publish ideas worth discussing. The views presented in the Opinion section are solely the views of the writer.

Contact Valentina Plevisani at [email protected].