Discovery of rare ape fossil fills evolutionary gaps, team with NYU prof. finds

Terry Harrison, a professor emeritus of anthropology at NYU, helped lead a study with significant effects on modern-day ape conservation.

An excavation of Yuanmoupithecus fossils near the village of Leilao in Yunnan. (Courtesy of Terry Harrison)

November 16, 2022

NYU anthropology professor Terry Harrison and a team of researchers recently discovered the world’s oldest gibbon fossil, helping clarify the evolutionary timeline of apes. The finding has revealed more information about gibbons, a family of primates related to humans.

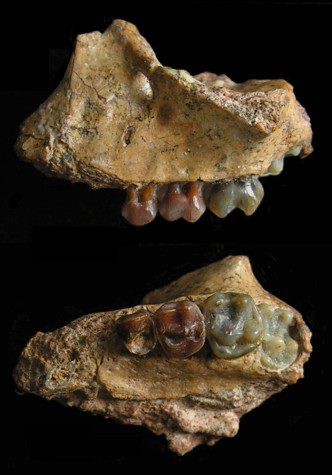

The research team, headed by Ji Xueping of the Kunming Institute of Zoology, discovered isolated teeth and the small jaw of a Yuanmoupithecus xiaoyuan infant, a particular species of gibbons, in the Yunnan province of China after decades of work in the area. The findings — dated as 7 million to 8 million years old — provide new insight into the primates’ sparse fossil record.

Harrison, a professor emeritus and co-author of the team’s study, was excited by the finding’s potential to advance the scientific understanding of primate evolution.

“Like a detective story, I put together clues to find something nobody else has even contemplated,” Harrison said. “It’s incremental, but they’re incredible things that blow your mind. We are never going to stop making outstanding discoveries.”

As a species, gibbons are believed to date back to around 17 million years ago, when they split from the evolutionary branch that would later become great apes. Researchers have found many gibbon fossils dating to about 2 million years ago in caves, but the 15 million years between remained a mystery until the recent discovery offered a better understanding of how gibbons evolved and where they dispersed.

Gibbons are long-limbed apes who currently inhabit rainforests across India, Burma, southern China and the islands of Southeast Asia. Smaller than great apes, gibbons use their elongated bodies to swing through the trees, hunting for soft, non-fibrous fruits to feed on.

According to Harrison, tropical forests tend to preserve fewer fossils than caves, oceans or lakes due to a lack of sediment to deposit on the bones. The bountiful predators and scavangers in tropical environments often eat gibbon carcasses before they can fossilize.

Due to the unfavorable environment, the hunt for a gibbon ancestor fossil spanned over 50 years. Research began in the 1970s when researchers from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing went on an expedition to Yunnan.

In the 1990s, Ji Xueping began working in the area. His search continued until September of this year, when his team was finally able to piece together the jaw of a baby and confirm the fossil as a Y. xiaoyuan.

Susan Antón, an NYU anthropologist who was not involved in the study, said she was excited about what the fossils revealed about the past.

“Genetic evidence tells us that there should have been fossils this old and older, but fossils are rare — and up until now, there hadn’t been any this old,” Antón said. “That means that studying these bones and teeth can now start to tell us something about how these animals lived, in what kinds of environments, and perhaps why they survived.”

Harrison explained that because the teeth were similar to those of many modern gibbons, Y. xiaoyuan must have been somewhere close to the gibbons’ common ancestor on the evolutionary tree.

“For example, gibbons are estimated to have diverged 17 to 22 million years ago, but their fossil record is known only from 8 million years ago,” Harrison said. “Understanding why certain species became extinct and why others survived can tell us a lot about the dynamics of evolution and what factors drive extinction.”

Deforestation currently threatens gibbon habitats in southeast Asia, and the International Union for Conservation of Nature considers the species to be endangered. Harrison said that researchers might gain a better understanding of modern extinction patterns by learning about how Y. xiaoyuan went extinct, and how other gibbons survived changes to the planet’s climate.

“In the next 200 years, we’re going to lose a lot of apes through habitat destruction,” Harrison said. “It would be a shame if we lost our closest living relatives. It might foretell what will happen to us.”

Contact Annabelle Wang at [email protected].