‘A city grieves’: How the Sept. 11 attacks upended life at NYU

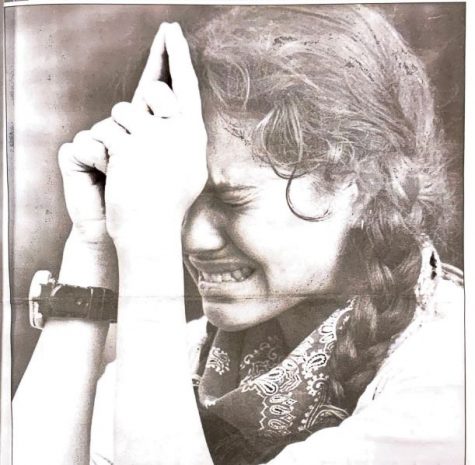

A review of WSN’s archives from the days after 9/11 reveals an aftermath of collective sorrow, despair and disbelief and shows how the NYU community scrambled to respond.

September 11, 2021

This story is the second of a two-part series commemorating the 20th anniversary of the Sept. 11 attacks on New York City. Read the first story here.

“In a brutal act of terrorism that may have left thousands dead, two hijacked planes crashed headlong into the World Trade Center yesterday, leaving the twin towers in a pile of burning rubble,” reads the opening line of WSN’s headline story on Sept. 12, 2001. In terse sentences, then-News Editor Brandt Gassman described the chaos following the destruction of the World Trade Center.

The series of reports published by WSN in the succeeding days chronicled how the attacks altered the lives of millions of New Yorkers and threw the NYU community into disarray. By virtue of its location in downtown Manhattan, the university sat at the heart of the tragedy.

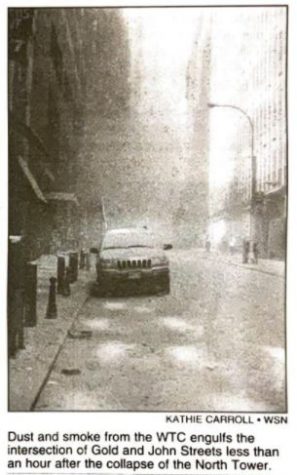

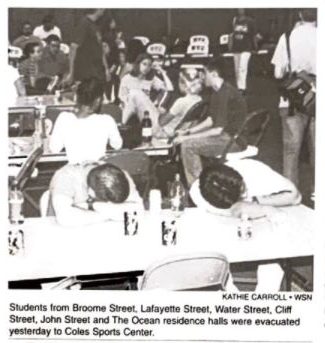

Students felt the blasts in their dorm rooms that morning. Train service was stopped for hours. Six residence halls were evacuated and eventually tested for toxic dust, including one at Water Street, only eight blocks away from Ground Zero. Thousands of students were temporarily sheltered at the Coles Sports Center, which has since been demolished and is now the site of the under-construction 181 Mercer academic building.

Gassman narrated the experience of Brian Foster, a WSN assistant editor and resident at the Water Street dorm, who “ran towards the World Trade Center after he was awakened by the second plane crash.” Foster stood at the intersection of Fulton Street and Broadway as the south tower crumbled. Recalling blocks of shattered windows and people covered in gray soot, he described the resounding crash as the “worst sound” he’d ever heard.

“I saw the person jump out of the south tower,” Foster was quoted as saying. “Everybody I was standing around went into hysterics.”

David Handschuh, an adjunct professor on his way to teach his first class of the semester, was thrown off his feet by the collapse of the south tower as he tried to photograph the scene. First responders pulled him from under a truck on West Street and into a nearby delicatessen to start treating his broken leg.

Later that day, NYU’s outgoing president L. Jay Oliva and incoming president John Sexton issued a joint statement of condolence.

“It is hard to capture this tragedy — this crime — in words, but we will say this: if New York City is known for anything, it is known for its determination, its courage, and endurance,” they wrote. “We share more than a name with this city — we share its characteristics and its virtues.”

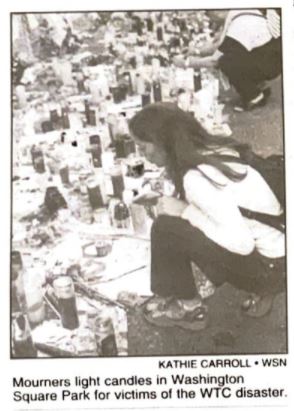

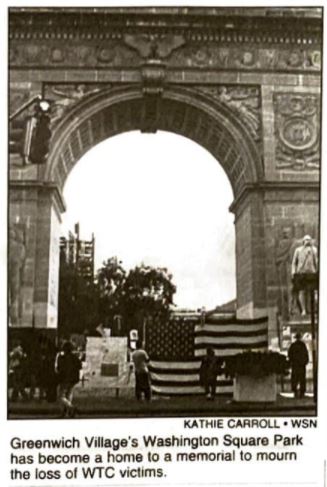

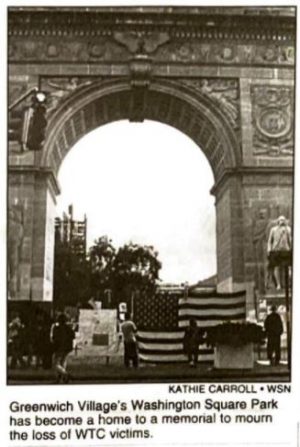

In the late afternoon, NYU students huddled together for a silent prayer vigil at Washington Square Park. The park used to offer a clear view of the twin towers before the attack.

Graduate students from the Stern School of Business set up supply drives in Union Square and Gould Plaza, collecting flashlights, extension cords and cell phone batteries to support the rescue efforts at Ground Zero.

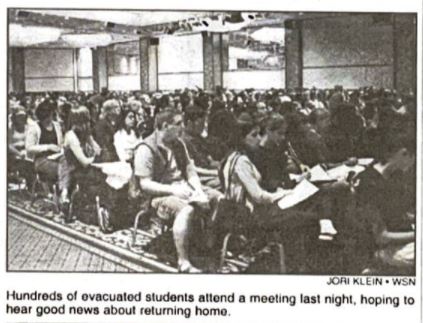

In the hours, days and weeks that followed, the initial shock of the attacks subsided, but their impact on university life did not. On Sept. 14, 2001, the administration announced that students displaced from NYU’s shuttered residence halls could move from the emergency shelter at the Coles Sports Center to the Sheraton New York and the Park Central Hotel, where the university had arranged for temporary student accommodation.

However, the university’s efforts were quickly overwhelmed. There were too many students to rehouse and not enough hotel rooms. NYU resorted to placing students in any empty space available in the few residence halls that remained open. A decision to resume classes on the morning of Sept. 14 was also met with surprise and incredulity on the part of students and faculty.

In the weeks following the attacks, as certain members of the American public grew increasingly suspicious of Muslims, “recorded cases of attacks and physical abuse against Muslim students […] created an atmosphere of fear.” A WSN story about the growing xenophobia quoted Areefa Arefin, a student at the time, who recalled being unable to grieve with her peers.

“It is a very difficult time to be an American Muslim,” Arefin was quoted as saying. “We are Americans and we wish [for] the time to mourn and show solidarity with other Americans, but we are often unable to do so because there is a sense that all Muslims are behind this, when that is not at all the case.”

In a Sept. 14, 2001, opinion piece titled “Take a look in the mirror, America, and ask why,” WSN columnist Nuno Andrade questioned the series of events that preceded the attacks and the response of then-President George Bush’s administration in their aftermath.

“Even if the U.S. government is successful in hunting down those directly responsible,” Andrade wrote, “what would a government-sanctioned revenge prove?”

Contact Arnav Binaykia at [email protected] and Suhail Gharaibeh at [email protected].