The Paris Theater showcased Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” this past Sunday, along with many other contemporary and classic films screened in immersive formats. Displayed in 70-millimeter film, it was a part of the theater’s “Big & Loud” series. Kubrick’s 1968 masterpiece remains hypnotic in its presentation and surprisingly profound in its human subtext for a film that prides itself on its technical achievements.

As the title suggests, the film is both a voyage into humanity’s future and a reflection of its past. Beginning with the iconic prologue sequence, Kubrick brilliantly sets the tone for the rest of the film by showcasing apes on a prehistoric Earth who discover their capacity for violence. When one suddenly realizes their very bones can be used as a weapon, the apes immediately use it to wage war on one another and establish power and dominance. The conflict comes to an end when a mysterious monument known as Monolith suddenly appears on Earth, inciting a mixture of fear and curiosity among the primates.

After the prologue, the film follows Heywood Floyd (William Sylvester), a scientist leading a mission to discover the Monolith, who serves as an allegory for human evolution sporadically throughout the film. During this sequence of the film, Kubrick unintentionally predicts technology that would be used in the 21st century, including electronic tablets and video calls.

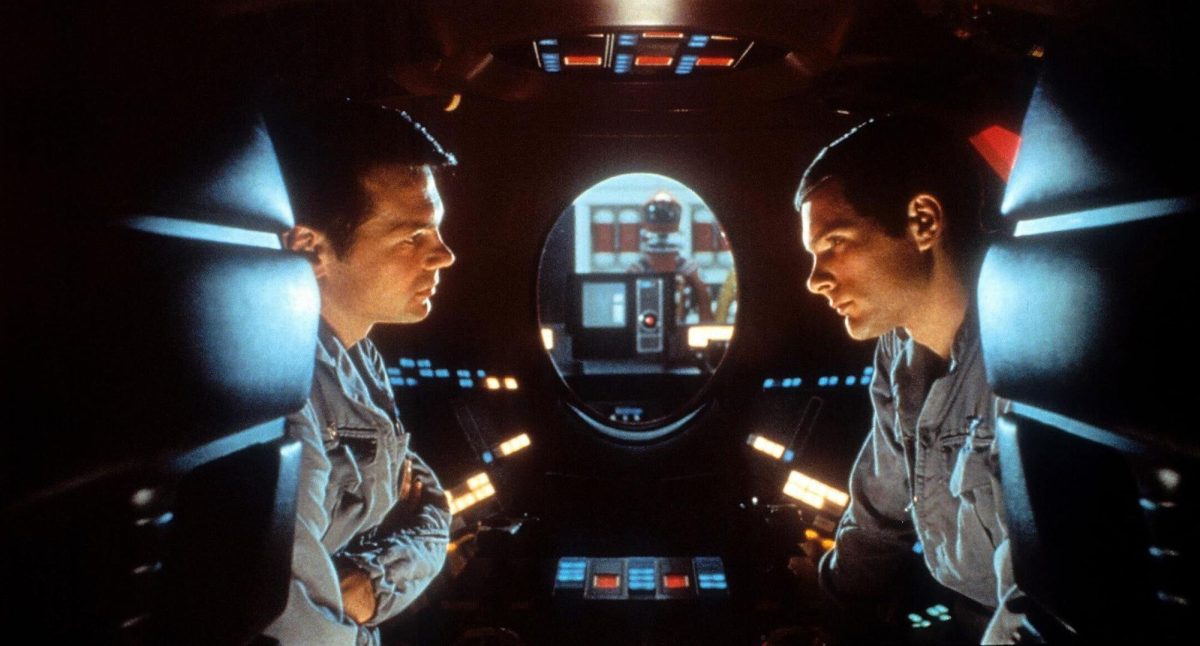

The film’s final act, arguably what it’s best known for, follows astronauts David Bowman (Keir Dullea) and Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood) leading a space expedition to secure the Monolith. They are aided by an advanced artificial intelligence, the HAL 9000 computer (Douglas Rain) — which controls many of the spaceship’s functions. The two astronauts are accompanied by three others in hibernation pods which induce sleep. When Bowman and Poole begin to doubt HAL’s capabilities, they plot to disconnect it from their system and go about their mission alone. However, HAL catches on to their plan, and out of paranoia and existential threat, attempts to kill each of the astronauts.

While “2001” is incredibly rich in its narrative intuitiveness, the picture is most famous for its astounding filmmaking. Using massive rotating sets, Kubrick and his team generate a strikingly believable world for audiences to immerse themselves in, with practical effects so convincing that they surpass the computer-generated visual effects in modern blockbusters. British cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth, who would later shoot Richard Donner’s “Superman” in 1978, captures the crew’s masterful craft in a mesmerizing way. Despite the film’s overwhelming ambition, the videography remains airtight and focused, often using simplicity to stir the viewer’s emotions.

The film is as much of an auditory experience as it is visual, famous for its extensive symphonic sequences. The sound design carries tremendous value throughout, both practically and narratively when building suspense — a skill Kubrick would replicate over a decade later in “The Shining.”

Technical merits aside, “2001” is a thematically striking film, and at points, even terrifying. The idea of discovery and leaping into the unknown is never once presented as a beautiful or even remotely positive thing. Every time mankind invents or comes across something new — whether it be apes using bones as weapons or scientists creating artificial intelligence — Kubrick frames it as a horror movie. It is almost as if the mere thought of creation is something to fear, not something to be encouraged.

“2001: A Space Odyssey” is an incredibly rare film in that it prompts the viewer to contemplate humanity’s ingenuity — not just for the sake of contemplation, but as something to actively worry about. It is a timeless, one-of-a-kind masterwork that demonstrates cinema’s profound narrative and artistic potential.

The film will have an additional screening at the Paris Theater on Friday, Sept. 15.

Contact Yezen Saadah at [email protected].