How COVID-19 affected my visa status

Family members catching COVID, apprehension by Swiss cops and a last-minute trip to Warsaw: my journey around Europe to obtain a U.S. visa during the pandemic.

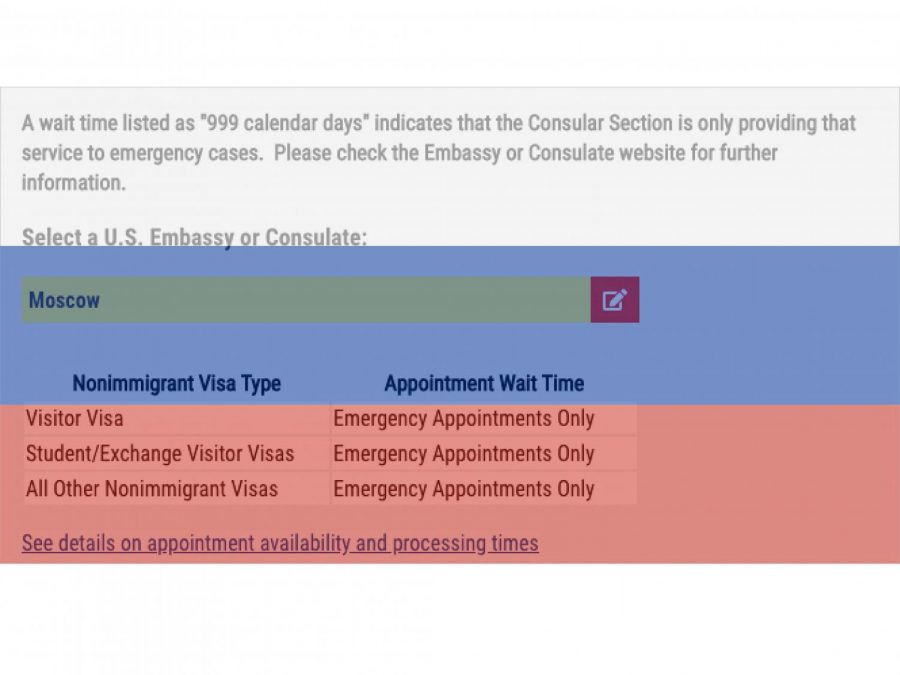

A screenshot from the US State Department’s Visa Appointment Wait Times page reveals the difficulty of obtaining visas of all kinds for individuals from Russia. Russian international students have to go through unusually extreme measures to study in the United States this year. (Staff Illustration by Manasa Gudavalli)

August 25, 2021

International students at NYU are familiar with the hardships of the visa process, but most don’t have to worry about renewing their visas until they’re already out of college. American students can just book a flight to New York City. Over the past year, though, my struggle to get a visa as a Russian international student has bordered on extreme.

It is difficult for Russians to study in the United States. As a Russian citizen, I am only able to get a U.S. visa for one year of university study at a time. This means that I am obligated to renew my visa every year in any country it is available. When countries around the world responded to the COVID-19 pandemic with travel and visa restrictions, I and many others were displaced.

On May 12, the U.S. embassy in Moscow announced that, with few exceptions, it would no longer issue visas. This news was unsurprising, as it followed the Russian government’s April 23 declaration that foreign nationals would be prohibited from working in the U.S. embassy. For international students like myself, though, the news set off a quest for the visa that would let them continue their studies.

I faced the beginning of the pandemic two years ago in Switzerland as a student at an international high school. After graduating, I was able to apply for a student visa in the Moscow embassy, but I was not able to go home — the European Union and Russia had suspended all travel, leaving me practically homeless for the summer of 2020. With the help of my high school friends, I went to Poland and got a visa at the beginning of August, just a month before I started at NYU.

As my first year in college drew to a close, I had to renew my U.S. visa for the upcoming year. To my surprise, I had met students here whose visas lasted for five years. These students, who sat right next to me in class, didn’t have to worry every 12 months about how they were going to get back to NYU. Moreover, not only were these students able to study in the United States for four years on one visa, they also had the opportunity to stay another year after finishing their studies. It seemed to me that it was just politics that was putting me and my fellow Russian international students through this annual ordeal.

By this time, Russian airlines had resumed some flights to EU countries, allowing me to finally go home. I fully believed that this was where my journey would end, but the pandemic made sure that it wouldn’t be that easy.

In order to renew my visa, I had to apply outside of the United States, and the embassy back home in Russia was no longer an option. I began looking for appointments all across the globe. Before the pandemic, you could go to any country with a U.S. embassy to get a visa. But with continuing travel restrictions, it was all but impossible for me to enter the EU.

In late May, I found out that one of our nannies at home had contracted COVID-19. My family needed my help to look after my 4- and 7-year-old siblings. Meanwhile, the situation in my home country — and my own home — was worsening. Cases were rising fast, yet there was no social pressure to get vaccinated. I had been lucky enough to get vaccinated in New York City, but COVID had reached my home and my family — within a week, both of my parents had contracted COVID-19. I had to get back home.

Though my family’s situation began to improve, I still didn’t know how I was going to get to NYU that fall. I started by getting a Greek visa, as Greece was the only country at the time issuing the Schengen visas that allow unrestricted travel across the European Union. For that reason, my family traveled to Greece for the summer holidays. I tried applying at the embassy in Athens, but the wait was months long. I checked U.S. embassies in cities across Europe — Madrid, Milan, Rome, Bern — but none would give me an appointment. These countries did not even have any obligation to provide an emergency appointment for someone like me without EU permanent residency or an EU passport.

After hours of research, I found that there were only a handful of cities where I could get a U.S. visa in time. I chose Paris, and planned a stop in Switzerland to visit my best friend after a year apart. My excitement to reunite with her grew as my flight landed in Bern, only to be immediately quelled: I hadn’t thought that I would be stopped by police as soon as I stepped off the plane.

With many foreign tourists circumventing the travel restrictions of other EU countries by getting Schengen visas in Greece, countries like Switzerland had started checking for EU passports or residency at the airport. The police in Bern took my Russian passport with the Greek Schengen visa. The 30 minutes that followed were the most stressful of my life — not knowing what would happen next, I called my parents and prepared to fly back to Greece or Russia.

After I explained myself to the authorities, telling them that I was coming to Bern in order to get a U.S. study visa, they let me pass. I walked to the baggage claim with tears in my eyes and a pounding heart.

I was all but ready to go get my visa in Paris when I found out that I would need to quarantine there for 10 days before my visa would even begin to be processed. I didn’t have that kind of time, so I had to devise a new plan: I got an appointment at the U.S. embassy in Warsaw, just as I had the year before, and successfully got my visa there. My journey to get back to school in the United States had taken me through Russia, Greece, Switzerland and Poland, but I was finally on my way.

No one trying to get an education should have to go through the process I went through. Hopefully, the governments of these countries can recognize the struggle international students face and this situation can improve in the future.

Contact Polina Tyurikova at [email protected].