After an attempt at retirement in 2013, 82-year-old Japanese filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki has returned with Studio Ghibli’s most recent project and his 12th feature film, “The Boy and the Heron,” which made its North American premiere yesterday at the 61st New York Film Festival.

Based on the 1937 novel “How Do You Live?” by Genzaburo Yoshino, “The Boy and the Heron” is the long-anticipated follow-up to what seemed to be the perfect career farewell with 2013’s “The Wind Rises.” Rather than attempt to top one of the most majestic and profound animated films ever made, Miyazaki creates an entirely different, individual work of art. Instead of creating a career-defining spectacle, Miyazaki’s newest work is a magical and personal tale of childhood, loss and discovery.

The film begins with 11-year-old Mahito Maki (Soma Santoki), who loses his mother Hisako in a fire in postwar Tokyo — a loss that shakes Mahito and fills him with guilt-ridden regret. This prompts him and his father Shoichi Maki (Takuya Kimura) to move to the countryside with his new stepmother Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura), who also happens to be his late mother’s younger sister. As Mahito settles into a new town at a mansion with Japanese-Western fused architecture, he forces himself to mature and shed the guilt he feels for not having been able to save his mother.

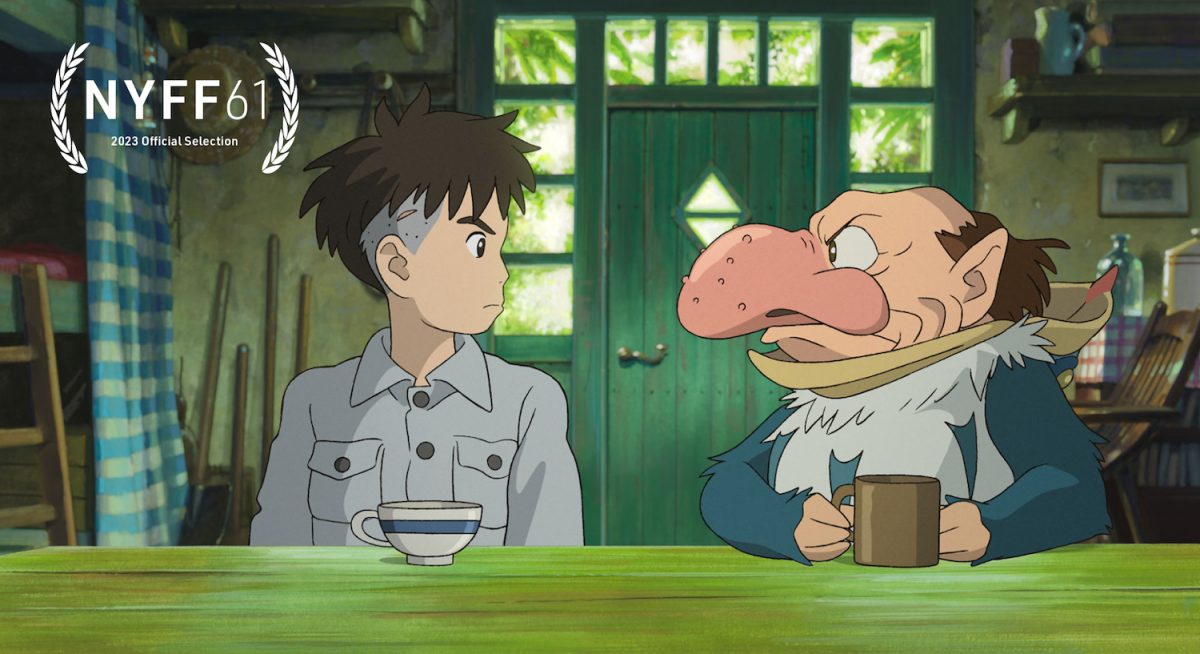

On the surface, “The Boy and the Heron” seems to carry similar traits to “The Wind Rises.” Both films are very grounded and subdued, tackling life, loss and isolation. Mahito tries to assimilate in his new environment with a pregnant Natsuko, who is doing everything she can to help him feel at home. Instead, Mahito shuts himself out from his stepmother and his father, even resorting to self-harm. His alienation, however, leads to the Grey Heron (Masaki Suda), a mystical, oftentimes annoying, talking heron who constantly tries to provoke Mahito. When Natsuko mysteriously goes missing, the heron helps Mahito to find his stepmother and uncover ominous secrets of the estate.

Just like any Miyazaki picture, the stellar, hand-drawn 2D animation proves to be the highlight of “The Boy and the Heron.” From the haunting backdrops and beautiful skies to the remarkably layered and textured nature of the characters’ movements, the film is surprisingly and masterfully innovative in its unlimited creativity. As the Grey Heron leads Mahito to a fantastical, dreamlike world, the viewer is introduced to many imaginative and visually ingenious locations and characters, ranging from a commanding, cosmic figure that governs the laws of time and space, to an army of man-eating, sky-soaring pelicans led by a parakeet king.

Miyazaki’s allegorical depth and gorgeous presentation is elevated by composer Joe Hisaishi’s majestic musical score. Hisaishi — who has composed the music for 10 of Miyazaki’s films, including “My Neighbor Totoro,” “Spirited Away” and “Kiki’s Delivery Service” — once again delivers work that is commendable, poignant and stirring, somehow balancing subtle, soothing tracks with bombastic orchestral splendor. As Mahito embarks on his journey to find his stepmother, he travels through a dimension of tonally evocative and moving melodies accompanied by the overwhelmingly superb artistic presentation.

“The Boy and the Heron” is not a mere culmination of Miyazaki’s work as a filmmaker — “The Wind Rises” has arguably earned that title — but is rather another unique, remarkably independent and free-spirited piece that proves the medium of traditional, authentic 2D animation is alive and well. Whether or not “The Boy and the Heron” is Miyazaki’s final film — which it most likely isn’t — his latest project demonstrates both practically and artistically that creative expression is defined by loss and grief, and that those emotions shouldn’t be shrouded by a misguided sense of pride and strength.

“The Boy and the Heron” will be screening at the New York Film Festival on Oct. 2, Oct. 12 and Oct. 14.

Contact Yezen Saadah at [email protected].