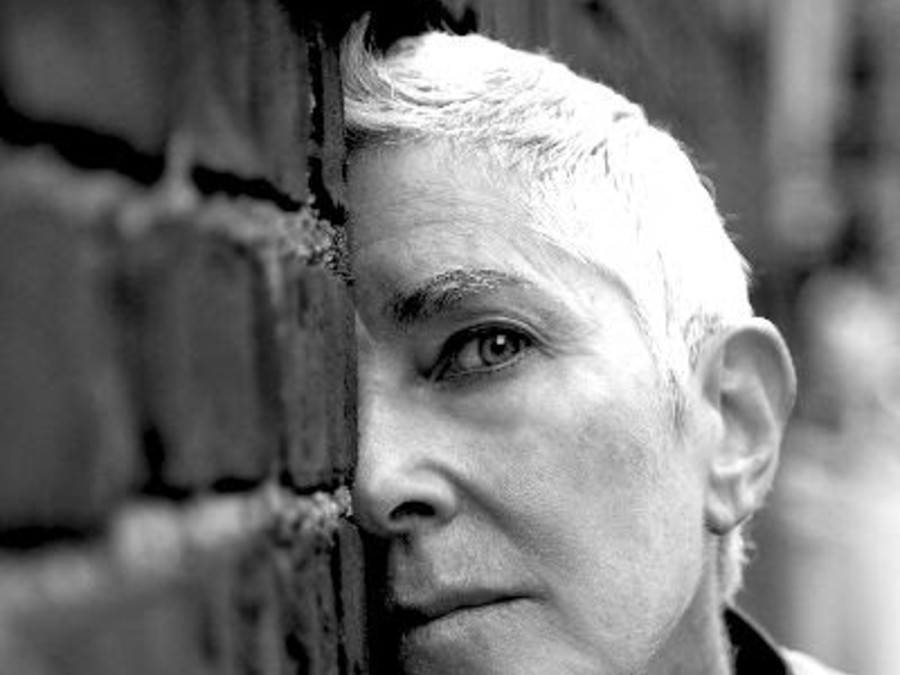

Q&A: Beth B on tackiness and transcendence

The filmmaker — a pillar of the New York underground arts scene in the ’70s and ’80s — spoke with WSN about New York City, alternative filmmaking and representation on screen.

March 27, 2023

“You may call the Bs punks,” wrote Jim Hoberman of Beth and Scott B in the Village Voice in 1979. “I think they’re space-age social realists.”

Beth B is skeptical of labels. Punk, futuristic, realist, no wave — to her, these are constraints under which artists find themselves obliged to repetition. She is more interested in the spaces between genres, as well as what film can do when it is experimental and socially-minded.

B has collaborated with artists like singer Lydia Lunch and photographer Nan Goldin as part of a downtown creative scene spanning art, music and film. Though B rarely finds herself in New York anymore, her work bears the unmistakable mark of the downtown in the ’80s, at once abrasive and communal, jaded and idealist. Decades after her emergence within the world of no wave, she has softened — her idiosyncrasy and unending devotion to the social potential of film, however, has remained unchanged.

Now, Metrograph At Home is featuring a vast array of her solo work in the series “Sex, Power, and Money: Films by Beth B,” from her minutes-long experimental shorts to longer narrative features and documentaries, as well as the work that blurs the lines between the two forms.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

WSN: Let’s start with your new film, “Glowing Evelyn” — what can you tell us about it?

B: “Glowing Annie” came first and then “Glowing Evelyn.” They actually evolved out of a theater production I just directed in the summer of 2022. Both Evelyn and Annie were characters in that.

I shot a lot of incredible films for the theater production and the whole time I was shooting them, I thought, “Oh my God, this is a film.” Not just a theater production, but I wanted to take the films that I was using as sets, the locations and emotional ties, I wanted to use them as films. I think the footage is very arresting.

WSN: “Glowing Evelyn” is especially visceral. How did the difference in medium affect that translation from theater to film?

B: To me, it’s all the same. I work in every medium: film, theater, sculpture, painting, large-scale multimedia installations, photography. What I always try to look at is work that is edgy, provocative, thought-provoking, mind-bending, perhaps disturbing and dark. I then figure out what medium would be the best to express the idea I’m interested in working on. The theater production evolved at the instigation of someone else and it was very much about Annie’s life. The film was extracted from the theater production but it was a separate entity, and it tells a different story. For me, storytelling is the most important thing, in conjunction with looking at challenging subjects.

WSN: For both of those you were working with a specific subject, a specific artist. Did they take the form of portraits?

B: They are kind of like portraits, but they’re also trying to look at the journey through pain that many people, but oftentimes women, take. What do you do with that pain? How do you transform your way of seeing that pain into something that you can eventually, perhaps, let go of? Some people can, some people cannot.

Personally, I have to work at that every day of my life, to bring myself into a place of positivity instead of being drawn into the dark side of things. This world is fucked. How do you have a positive outlook when there’s a kind of prejudice, racism, xenophobia, military insanity, people being killed for absolutely no reason at all, wars? At a certain point you have to consciously go, “How can I turn some of my own angst into something that is transcendent or can touch others?”

WSN: There was a review a while back —

B: [Laughs] We don’t read reviews.

WSN: It was a bit amusing, from what seemed to be a very frustrated New York Times critic. It was from 1982 —

B: Oh, God, 1982! Nobody knew what to do with my work for many, many years. I’m always way ahead of my time. That sounds like I’m having an attitude, but I’m not, really. Sometimes it takes 10 years, sometimes it takes 30 years for people to go, “Oh my God, that’s what that — oh, she’s talking about trauma,” 45 years ago. But there wasn’t a word for a lot of things that were going on.

WSN: The reporter wrote that your films were “amused by a pop sensibility that interprets a rudely bland kind of cinema tackiness as a statement not just on movies but also the human condition.” How do you think non-commercial or alternative forms of filmmaking can intervene when informed by “tackiness” or “pop”?

B: Well, it’s valid to people who want to see that kind of stuff, who don’t fit into the mainstream. I don’t fit into the mainstream. I’m not aspiring to that, I’ve never aspired to that. I’m like, “bring it on.”

People who are feeling outside of what is “normal” — it’s an alternative way of living and looking at life. It’s challenging the status quo. We’ve got to do that. We’ve got to speak out, especially as women. When I was younger, it was very hard to assert myself as a woman. I’ve always been outspoken and aggressive, but they were very difficult times.

WSN: You’re often identified with the no wave movement as an artist. What do you think of that classification?

B: I hate all classifications. They put you in a box and limit what your mind can do. It’s convenient for whatever, but I would just say I’m of the Beth B aesthetic and I continue to do my work. No wave was where I started, but it was so long ago. A lot of people are stuck in that place and it was fabulous, but now it only exists in nostalgia.

Now, I’ve become gentler and kinder. I don’t beat people over the head with what I want to say anymore, but it’s still provocative and thought-provoking work. I’m trying to confront people and get them out of their comfort zone. The greatest reaction is when someone cries after one of my films and realizes, “There are other people like me.”

WSN: When you were making films in the ’80s and ’90s, sex and violence were more taboo on screen.

B: Well, it was always portrayed, but with weapons wielded against the women. Violence was creating a victim, and the victim was always a woman. The aggressor was male. My films always turn the table. They all have female characters who are saying, “Fuck you.”

WSN: Now that representations of sex and violence are more acceptable on screen, more media is saturated with what might have previously been considered “explicit content.” Are there new themes you’re interested in or new modes of representation?

B: Tons. I don’t advocate violence at all, but I think sometimes you have to show things so that people can perceive them in a different way or come to their own conclusions about how they feel about violence. Sometimes when you show something that might go too far, it helps us figure out what our own boundaries are. What is too dangerous, why do I feel disturbed by this? It can open up a whole conversation that goes beyond just the act of violence. We have to think about how we portray violence, whose point of view. To me, it’s very important to protect women, children — people who are vulnerable. Often in the mass media, forget it. They just want to sell tickets and make money. The easiest targets to aim the violence at are women. I think the most important thing is to raise questions about how we are such a violent country and world.

WSN: In some of your films, you incorporate footage from television and news media. In “Out of Sight/Out of Mind,” it was related to the Eric Smith case. That’s become quite popular over the past few decades, appropriating that cultural material for filmmaking. What do you think that allows for in filmmaking?

B: I think sometimes people can hear something or say something, and they dismiss it because they think it’s not really happening, and would never happen. I try to bring fact into what someone might think is fiction. In “Amnesia,” people say things that are rather horrific, racist, and we have footage of Nazi officers marching. The idea that history just keeps repeating itself over and over, and bringing in imagery from years ago and the present, gives us a point of historical reflection. It breaks the fantasy that it will never happen here. The film is saying that it has happened. It is happening.

WSN: In light of those categorizations of fact and fiction, how do you approach genre distinctions between documentary and fiction?

B: Before there was the word “hybrid,” I was making hybrid films in the ’70s, combining true stories with fiction. It mashed them all together. Every film is different, sometimes I do pure documentary filmmaking. But I look to the person or people that I’m doing the documentary about to reveal the story to me. I’m attracted to a character or personality that I know or don’t know, and there’s always a bit of a mystery that I want to excavate, to find a story that perhaps that person has never talked about. Often, it’s women’s stories, because they’re seen in our society as outcasts or not within the normal realm of acceptability. I’m interested in the people who don’t have a voice, and I see filmmaking as giving a voice.

WSN: Do you think that sensibility of using art as a form of activism was influenced by your being in New York in the ’80s?

B: My entire life, I felt that something was wrong with me, that I was a reject. I had to fight to have my voice heard or even acknowledged. It’s a continuing struggle I see everywhere with people who are taught that they’re not valued. As soon as I stepped into the city in the late ’70s, I felt it was my home and these were my people. It was a devastated landscape and that’s how I felt inside my own body. It was destroyed, and I had nothing to lose. It was freedom. I could do anything. I wasn’t doing my work to satisfy anybody, I just had to do the work. I was so hungry to express myself, and so were many of the people of that time. Nobody had money or ambition.

But I escaped this city. It’s not the city that I came to love. The way that New York has evolved, it’s gone from a creative Wild West to the taming of this horrible shrew of money and success. Everyone’s trying to be seen, you know what I mean? I moved out of New York fifteen years ago, and I love Savannah. I’m trying to lure people down there so we “blue” the state up a little bit. It is the most phenomenal place. I went to the beach last week and swam in the ocean. Now what are we doing here?

“Sex, Power, and Money: Films by Beth B” is available to stream on Metrograph At Home.

Contact Katherine Williams at [email protected].