Remembering Godard: Formal innovator and revolutionary poet

In a career that spanned over sixty years of film history, Jean-Luc Godard revolutionized the art innumerable times. In light of his sudden passing, WSN revisits his life’s work and the indelible imprint he left on cinema.

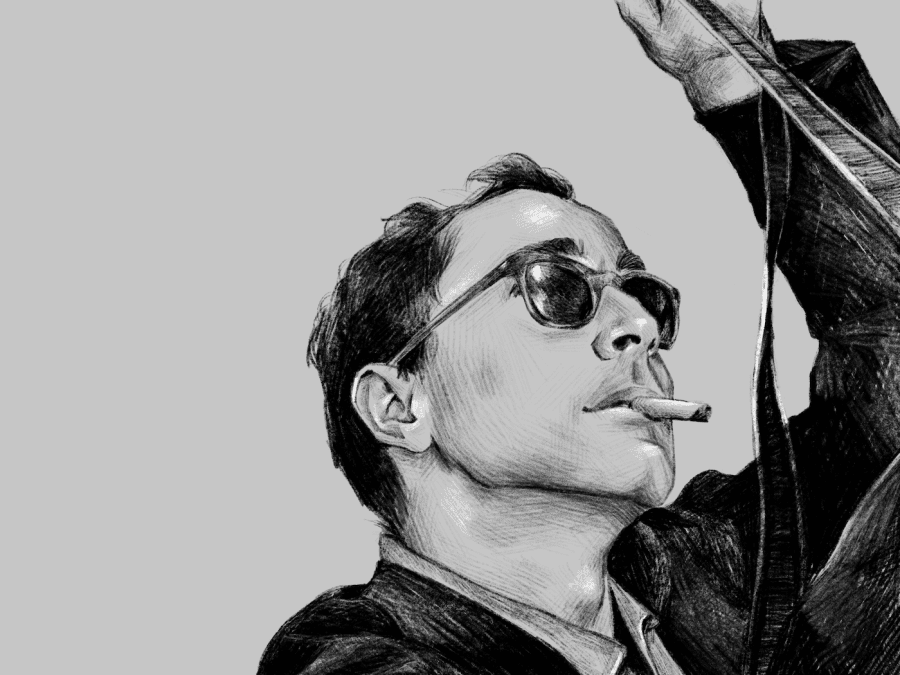

After a more than 60-year career, Jean Luc-Godard set the stage for the filmmaking that we see today. (Illustration by Victoria Liu)

September 21, 2022

In the week since his sudden passing, much has been done to remember French Swiss filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard. As critics worldwide pay him tribute, amateur archivists resurrect his wisdom by sharing old quotes and clips online, and cinephiles revisit his oeuvre, Godard’s titanic impact on the cinematic medium has made itself more evident than ever. Always at the vanguard of filmmaking — armed with an unparalleled comprehension of the medium’s form and history, as well as an unwavering Marxist disposition — Godard pushed the artform to its breaking point not once or twice, but every time he set out to film over a career of more than 60 years.

Though typically associated with the French New Wave for reviving French Cinema — and frankly, world cinema — by disrupting the post-war commercial dullness of the art form, Godard’s influence on film predates his intervention on its visible form. Godard began as a critic for the prominent film journal Cahiers du Cinéma, much like the rest of the French New Wave crowd. The journal’s headstrong commitment to interrogating film’s evolving form, criticizing its malpractitioners and evaluating what separated good directors from bad ones — thank Godard and company for today’s universal love toward Alfred Hitchcock, Nicholas Ray and Jerry Lewis — laid the foundation for the future of filmmaking.

Having started a fresh theoretical approach to film in writing, Godard brought newness to the medium with the simplicity of a cut. To be precise: a jump cut. The startling use of said cut, one which challenged age-old notions that films ought to maintain a continuity of space and time, began Godard’s long, unpredictable riff on film; the jump cut in 1960’s “Breathless” altered the medium’s grammar forevermore. The employment of the technique displayed the ease by which new trajectories could be conceived apropos of cinema’s evolution, and jumpstarted a new set of formally involved disciples who would continue to toy with his fresh ideas.

Having broken age-old traditions with his inventive editing, Godard continued making fun, flimsy, often sadistically romantic films of an increasingly political bend. These films paralleled the boiling veins of a fuming French population that erupted in May 1968, a month of revolution. At a time when increasingly troublesome politics take hold of the world — America’s glissé into fascism, Brazil’s neglect of ecological devastation, Chile’s failed leftward shift, and the alphabet goes on. Is it still possible to imagine a revered, mainstream filmmaker making a formal artistic argument against the horrors of the world?

Given Godard’s alignment with revolutionary Marxist ideals, it’s only natural he stood against the French colonization of Vietnam, “Loin du Vietnam”; invoked radicalism within the French youth, “La Chinoise”; denounced the bourgeoisie that replaced his nation’s guillotined nobility, “Weekend”; and desecrated the flag for which he no longer supported, ““Film-Tract n°1968.” After participating in major protests associated with May ‘68, standing alongside students and workers, he publicly admitted to pandering to haute, apolitical intellectuals and disowned all of his early films. Devising a new, more politically-active film form, Godard formed the Dziga Vertov Group alongside Jean-Pierre Gorin. Later on, he’d stand by Palestine while acknowledging and attempting to correct the faults in his work as a political filmmaker, as in “Here and Elsewhere.” Ambitious to leave the world a better place than he found it, Godard’s commitment to a revolutionary lifestyle, in practice and personality, was a quality that distinguished him from his peers and the present slosh of apolitical filmmakers fueling our cultural crisis.

While it is true that Godard’s output fluctuated throughout his career, particularly as he began experimenting with video during the ‘80s, his perseverant mindset as a critic allowed him to remain one of the most formally interesting filmmakers up until his last movie, “The Image Book,” at the age of 88. This final film, which historicizes cinema, is demonstrative of his care for the medium, and skillfully navigates the tropes most movies about movies fall back on.

Godard’s partner, Anne-Marie Miéville, with whom he co-directed many intellectually enriching and artfully effusive films, remains. His ideas remain too, imprinted on light and spread across the globe. As the years continue, Godard’s influence on the burgeoning medium of cinema will only become clearer. In a similar way we commemorate Brunelleschi’s contributions to painting, Godard’s acceleration of cinematic conventions — from the simple jump cut to his political challenges upon film-making and its distribution — lands him in the company of film poets like Sergei Eisenstein, Maya Deren and Orson Welles.

Contact Nicolas Pedrero-Setzer at [email protected].