In the popular discourse regarding “Poor Things,” audiences have repeatedly tried to categorize this label-rejecting film. A quick Google search finds “Poor Things” labeled as a sci-fi, a dark comedy and a drama. Others have labeled it a horror or a coming-of-age film. Fans have dubbed it a freeing, feminist masterpiece while critics condemn it as a backwards, male fantasy version of female empowerment. In her Golden Globe acceptance speech for portraying “Poor Things” protagonist Bella Baxter, Emma Stone threw rom-com into the mix, as her precocious character “falls in love with life itself, rather than a person.”

But much like Bella, “Poor Things” is unrestrained, straddling genres and philosophies until they become lenses through which viewers can understand the film rather than classify it. Genre should not be a filmic code of law, rather a framework for analysis. In following the film’s spirit of experimentation and adventure, an additional hypothesis is that “Poor Things” is the ultimate modern monster movie — a paragon of this genre’s confused navigation of gender and class politics in the 21st century.

Cinematic monsters have long represented the West’s fear of the other, from vampires symbolizing sexual deviants to UFO invasions thinly disguising immigration panic. Tales of the inhuman have always sought to reveal what it means to be afraid of the human. In that sense, “Poor Things” is a creature feature no different than its predecessors. But what it means to be a human woman — or even a kind person — in Western culture has changed since “Frankenstein (1931),” “Dracula” and “Mars Attacks the World.”

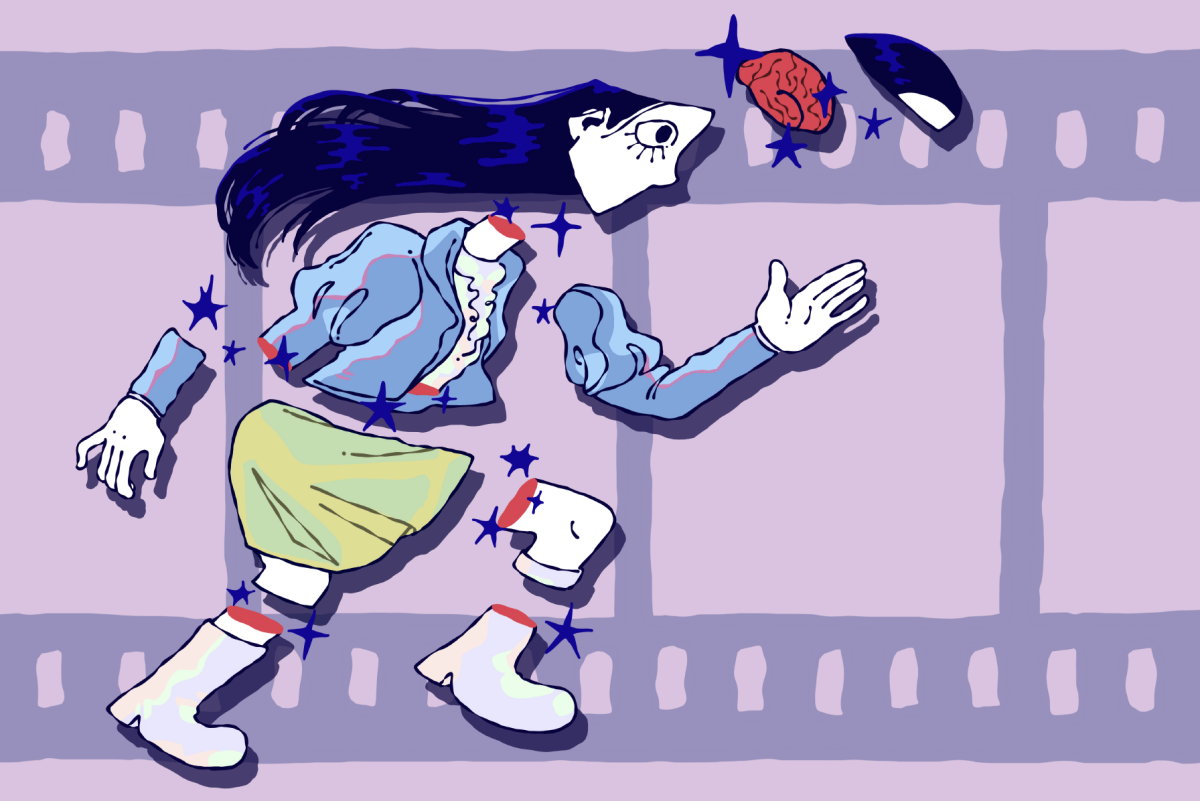

There is a notable similarity between Yorgos Lanthimos’ “Poor Things” and Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein.” In “Poor Things,” Bella is resurrected by a scientist after a suicide attempt, and goes on a journey of self-discovery within her deeply repressive society. Like Frankenstein’s monster, Bella starts the film as a blank slate. Wiped of memories from before her revival, she must rediscover language, sex, class relations and all the good and the bad of Western culture. Confidently searching for good in a difficult world, Bella resembles a more optimistic Frankenstein’s monster from when he says “Beware; for I am fearless, and therefore powerful.”

Beyond being a gender-swapped version of Frankenstein’s monster, Bella is the monstrous synthesis of the West’s worst fears. Bella is an alien; she is also a vampire. One could make a case for an undead zombie or a moral-stirring witch. Perhaps most terrifying of all, she is a woman in a patriarchy.

The first shot of “Poor Things” is of Bella’s pregnant mother jumping off a bridge. With the mother’s death, Bella’s brain is put into the mother’s head, and the body carries what will become Bella’s body and brain; her arrival is like that of a UFO. While Bella does not have fangs, her Victorian-style dresses and carnal pursuits elicit visions of vampires past. Mark Ruffalo’s character, one of Bella’s rejected suitors, even likens her to a lustful, life-sucking “demon at large in the world.”

Yet being monstrous is womanhood. It is attempting to make sense of the world, invading prohibited spaces, and discerning who to trust in sex and life.

The monsters and rebellious women of films past would have gotten their narrative comeuppance, but Lanthimos’ monster movie is a lot kinder to its symbolic humanoid — even if its satire bites harder. Whereas UFO movies of the past would witness the bravery of humans as they eliminate the invasive species, “Poor Things” allows Bella to be a force for positive change. And Bella is not Dracula; rather than burning in the light, she thrives in uncharted territory. At times she may feel as though there is no place in which she can pursue independence, but she fights against her father’s, suitor’s and culture’s imprisonment and actually triumphs — all in a petticoat.

But complications arise from the festering wound that is the legacy of the monster movie, a genre that demonizes the non-white, cisgender, heterosexual male. The film’s sexually degrading and infantilizing lenses do not outweigh Bella’s ultimate victory over her patriarchal surroundings. Bella is sexualized before she is even taught to read. Although she has the brain of an early teenager, she is sometimes forced and sometimes willing to undergo intense sexual acts, which is almost always played for laughs. Fostering conversations about what constitutes good feminist representation is important as genres and humanist thinking continue to develop. But filmmakers like Lanthimos need to open these wounds and cleanse them, even if it’s messy and stings.

There is a place for the monster movie in the modern film industry, and “Poor Things” is trying to figure out where that is. Combining the West’s most feared and othered monsters into one, “Poor Things” represents the monster movie starting to reassess its fearful history, push the genre forward and recognize that to be human is to be monstrous — a stitched-together model of what one thinks is moral and good. What do the monster movie, and film industry at large, think is moral and good? “Poor Things” doesn’t know, but it sure is trying to find out.

Contact Liv Steinhardt at [email protected].