Through its unique approach to the display of works by Renaissance masters, such as Hans Memling, Lorenzo Lotto and Titian, “Hidden Faces: Covered Portraits of the Renaissance” invites viewers to examine the hidden emblems and allegories that adorn the backs and covers of the era’s portraits. It challenges the typical consideration of paintings as two-dimensional, single-sided works hung on a wall.

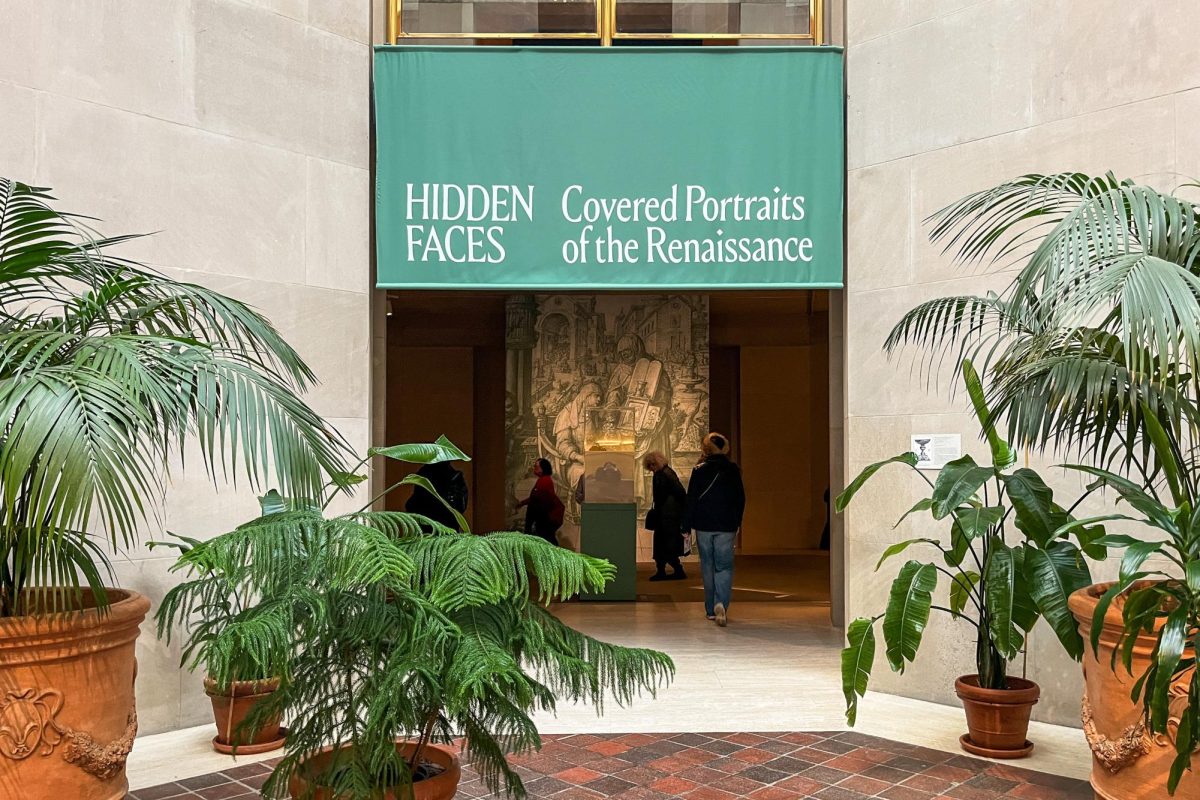

Displayed in the rooms surrounding the sunlit courtyard in The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Robert Lehman Wing, “Hidden Faces” explores the Renaissance tradition of multisided or concealed portraits. The exhibition features roughly 60 Renaissance portraits from Italy and northern Europe that are divided chronologically into five sections by region, beginning with ancient secular and sacred art and followed by portraits from 15th-century northern Europe, 15th-century Italy and 16th-century northern Europe, and portable portraits.

To showcase the portraits’ reverse sides, “Hidden Faces” takes a unique and compelling approach to its displays, and this is arguably the most intriguing part of the exhibition. Many of the works — rather than being hung on the galleries’ walls — are placed on pedestals or in glass vitrines at the center of the galleries. These pedestals provide a 360-degree view of the works, offering a rare opportunity to see the paintings’ reverse sides and revealing how Renaissance artists used them to reflect or contribute to the portrayal of the person in the portrait.

The four sections of “Hidden Faces” feature pieces from Italy and northern Europe during the 15th and 16th centuries, showcasing a variety of double-sided and covered portraits. The exhibition highlights the use of reverse sides or portrait covers to indicate the subject’s status or traits through emblems, like coats of arms, or allegorical paintings of various virtues. Particularly interesting is Hans Memling’s 1485 “Portrait of a Man” — a bust-length portrait of a man with his hands together in prayer — with a painted vase of irises on its reverse. Through the irises’ allusion to the Virgin Mary and the vase’s design referring to Jesus, the reverse not only indicates the man’s devoutness, but is also “one of the earliest known, independent still lifes.”

Bernhard Strigel’s portraits of Margarethe Vöhlin and Hans Roth show the married couple facing each other in three-fourths profile, dressed in fine clothing, with aligned landscapes visible through windows behind them. But it is the more recent changes made to the portraits’ reverse sides that make them particularly compelling. While they originally featured painted versions of the subject’s coats of arms, a museum’s collection sticker has been added to the back of Vohlin’s portrait, and both pieces have cradles — wood slats added in the 19th century to provide structural support. The backs of these portraits are not typically exhibited, but become an important part of the work when shown in a vitrine. These details highlight how modern alterations can change our understanding of how double-sided works should be displayed.

“Hidden Faces” also features portraits with painted covers, such as Lotto’s 1505 “Portrait of a Woman” and its assumed cover, “Portrait Cover with an Allegory.” The portrait is a naturalistic, bust-length image of a woman in front of a green curtain — referencing the curtains that were traditionally used to cover private portraits. The cover juxtaposes a cupid showering a woman with flower petals and two satyrs, contrasting chastity with lust. As a result, the cover’s moralizing theme conveys the chastity and virtue of the woman in the portrait. The inclusion of these works in “Hidden Faces” is also notable because they have been reunited from two different collections: The portrait is on loan from the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon in Dijon, France, and the cover is from Washington, D.C.’s National Gallery of Art.

It should be noted that the organization of the paintings on the galleries’ walls can make it difficult to imagine how the portraits and their covers may have fit together, or how two separate portraits may have been originally hinged together. However, “Hidden Faces” does include two animated reconstructions of covered portraits — one of Ridolfo Ghirlandaio’s “La Monaca” and it’s cover, and the other of a mirror frame with two sliding shutters — both of which play in a loop on small screens mounted on the wall.

Above all, “Hidden Faces” presents viewers with a new perspective on Renaissance portraiture and encourages a consideration of the interactive, inventive nature of the era’s art. By displaying many of the portraits and portable pieces on pedestals, the exhibition subverts the usual understanding of paintings as immovable, permanent pieces mounted on walls, inviting viewers to explore the personalized and intimate ways that portraits were used during the Renaissance.

“Hidden Faces: Covered Portraits of the Renaissance” is on view in The Met’s Robert Lehman Wing until July 7. The exhibition is free with museum admission, which is pay-what-you-wish for NYU students.

Contact Katherine Welander at [email protected].