In the 1970s, downtown Manhattan saw an artistic renaissance. As New York City grappled with rising crime levels and financial ruin, the bohemian art scene emerged, ushering in a rebellious new era of creativity. The Lower East Side became home to legends in the making — Robert Mapplethorpe, Allen Ginsberg and Andy Warhol, to name a few — as its art scene rapidly grew. In the midst of downtown’s star-studded scene worked Peter Hujar, an American photographer who documented the area through the ’70s and ’80s.

Hujar worked at the intersection in the area’s queer and bohemian art scenes, photographing the two worlds and the people who struggled to keep them alive. During his lifetime, Hujar never achieved the level of notoriety of his contemporaries — largely due to his own rejection of institutional gallery showings — his piercing black-and-white photographs have posthumously cemented him as a legend. A collection of his photographs tracing New York City’s queer landscape, compiled in a series entitled “Echoes,” is currently on view at 125 Newbury until Oct. 28.

“I photograph those who push themselves to any extreme,” Hujar once said of his work. “That’s what interests me, and people who cling to the freedom to be themselves.”

Clinging to the freedom to be oneself was the spirit of post-Stonewall Manhattan. The ’70s saw a blossoming of LGBTQ+ culture in New York City — from the ballrooms of Harlem to the buzz of Greenwich Village’s Christopher Street. Pockets of queer communities arose throughout the boroughs, and Hujar immersed himself within them. The exhibition features works that capture how Hujar engaged with downtown’s gay culture through portraits, nudes and his documentation of the Christopher Street Pier.

Hujar photographed the Christopher Street Pier — namely piers 45, 46, 48 and 51 — extensively. In the early half of the 20th century, Manhattan’s piers served as a port for merchant ships. As shipping declined, and the city eventually abandoned the piers in the ’70s, the dilapidated waterfront became a popular site for gay cruising, and its liberating environment provided a refuge for many homeless queer youth of color. Existing on the outskirts of Manhattan, the piers, far away from society’s scrutinizing eyes, became a place for existence without the fear of retribution for New York City’s queer population.

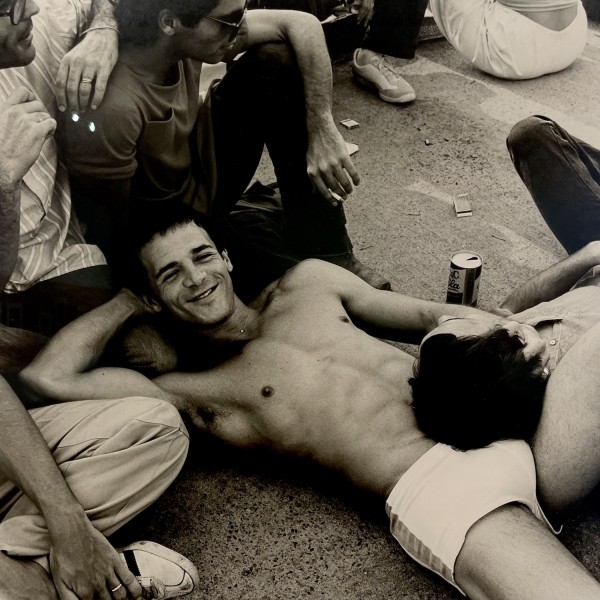

The photograph “Christopher Street Pier #3, 1976” is a scene of joy. Hujar captures a group of men lounging on the street, their bodies entangled. In the center of the photo lies a half-naked man, gazing up at the camera with a crinkled grin as he rests on the legs of two men while holding the head of another on his lap. Bodies lie upon each other, pressed skin-to-skin in broad daylight, the fear of being rebuked for their intimate proximity thrown to the wind.

Hujar’s work is rife with intimacy, a quality only he, as a gay man photographing fellow queer people, is able to obtain. Hujar has often been compared to the likes of Diane Arbus, who similarly photographed LGBTQ+ individuals. Unlike Arbus, however, Hujar creates no sense of “the other” in his work. He embraces his subjects as equals. Understanding that his subjects are already outcast by society, Hujar’s portraits celebrate them, turning their bodies into art.

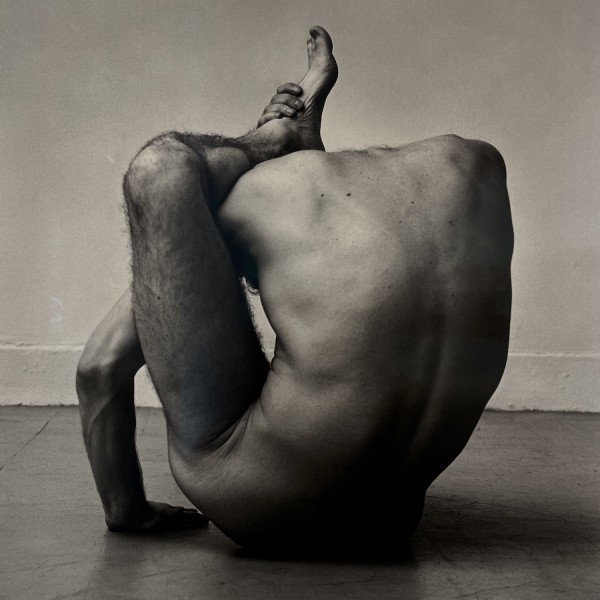

His subjects, though often stripped bare in front of the camera, show no hesitation and meet the camera’s eye with unwavering gazes. In “Gary Schneider in Contortion (II),” the titular Schneider sits on the floor of Hujar’s studio, his back to the camera. His head dips as he uses his right arm to hold his left leg over his head, while his left hand remains firmly planted on the ground. Schneider’s body, though flexible, is still tense, and bathed in differing values of light. Through his nudes, Hujar captures the contrasting expressions of one’s self through expressions of the body, all the while daring viewers to see sensual photos of men taken by other men.

Among the featured images is a portrait of David Wojnarowicz, a prominent photographer and queer activist in New York’s Lower East Side, who was briefly Hujar’s partner. Hujar’s featured portrait of Wojnarowicz is tender, capturing the artist-activist lying atop a pillow as light gently illuminates his features. The two, despite not remaining lovers, stayed fixtures in one another’s life. Hujar was a great mentor to Wojnarowicz, and they remained close until Hujar died of AIDS-related pneumonia on Nov. 26, 1987.

“Peter Hujar: Echoes” comes to us at a time when queer bodies are, once again, being increasingly vilified. In viewing Hujar’s photographs, we become witness to revived history. Hujar’s queer New York City whispers to us, reminding us of the LGBTQ+ community’s undying legacy of endurance. His photographs, which capture downtown Manhattan’s gay scene in all its past pain and glory, instill faith in modern viewers that even in the face of a hatred that seems insurmountable, we, just as our predecessors did, will overcome.

“Peter Hujar: Echoes” is currently on view at 125 Newbury until Oct. 28.

Contact Adrita Talukder at [email protected].