‘Georgia O’Keeffe: To See Takes Time’ welcomes viewers into scenes of solitude

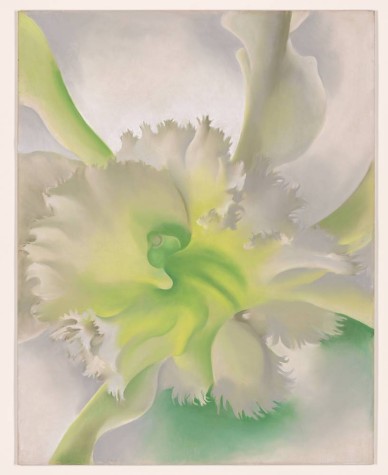

Georgia O’Keeffe is more than her sexualized flower paintings. The MoMA’s newest exhibition presents more than 120 works spanning over four decades of the pioneering American artist’s career.

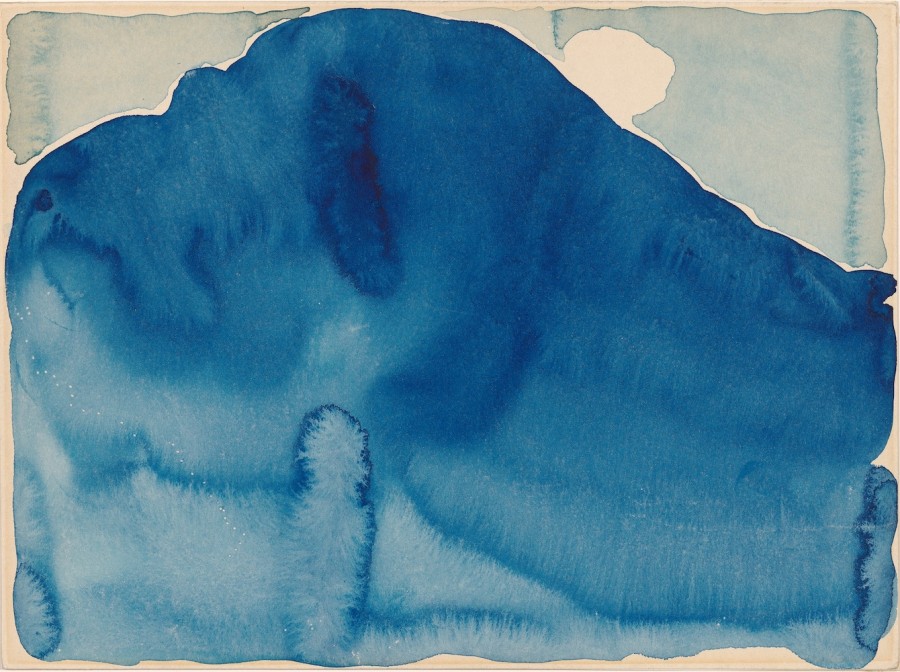

Georgia O’Keeffe. Blue Hill No. II, 1916. Watercolor on paper, 8 7/8 × 11 15/16″ (22.5 × 30.3 cm). Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. John B. Chewning. (Courtesy of Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

May 1, 2023

An ode to the places she has lived, “Georgia O’Keeffe: To See Takes Time,” a new exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, includes several series of subjects and material experimentations on paper. The retrospective is the first of its kind to highlight O’Keeffe’s drafts for large-scale paintings and works on paper rather than traditional canvas. It is a testament to her lifelong devotion to the American landscape.

Raised on a Wisconsin dairy farm, O’Keeffe would forever be influenced by American scenery. Having previously worked as a freelance commercial artist and art teacher, she arrived in New York under the patronage of leading photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz. They married in 1924. As Stieglitz’s wife and muse, she and her work were viewed by the public as an extension of her husband’s intimate photographs. As her work gained attention, she was eventually recognizable on her own. She was not only a part of her husband’s art, but stood out independently. But her true love was not Stieglitz, but the American Southwest. Inspired by her surroundings, O’Keeffe is known for her paintings of animal bones, flowers and landscapes. She would reside in northern New Mexico until her death in 1986.

“A flower is relatively small … Still — in a way — nobody sees a flower — really — it is so small — we haven’t got time — and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time,” O’Keeffe wrote. “So I said to myself — I’ll paint what I see — what the flower is to me but I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it — I will make even busy New-Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers.”

In 1946, O’Keeffe became the first woman with a retrospective at the MoMA. She rejected the title “woman artist” throughout her entire career, only to be championed and critiqued as a second-wave feminist whose close-up paintings of flowers bore resemblance to genitalia. In her eyes, she was only an artist and flowers were only flowers. Her studied perspective is not the same as that of a hurried viewer. Seventy-seven years later, her second MoMA retrospective is a reminder of the progress she’s made, intentionally or not, for women artists and modernism.

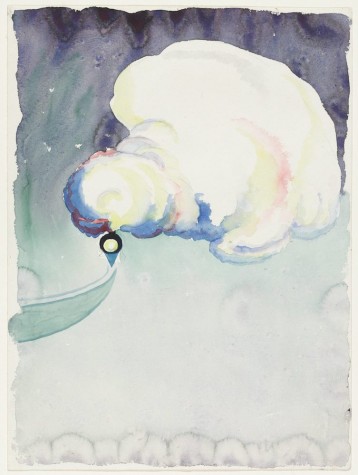

Arranged chronologically and by subject matter, her works of charcoal, watercolor, graphite and pastel hang on the walls in mismatched frames. O’Keeffe has depicted mountains, skies, trees, waves and incoming trains in her diverse collection of artwork. Visitors walk around the galleries in the same swirling motion as the waves and abstract figures on display. O’Keeffe’s journey begins amid candy-colored mountains and intense blues and reds; the visitor follows her movement across her periods of creative growth.

O’Keeffe paints people as if she’s already disappointed in them. Her nude self-portraits are elementary, with awkward poses and eyes that are too big for their faces. Perhaps she had grown too comfortable in front of Stieglitz’s lens to portray her own body as he had. Photographer Paul Strand is nowhere to be found in several untitled abstractions of him. Painter Beauford Delaney’s face floats like an apparition in a sequence of three until she paints him a crisp white collar. All three subjects are failed experiments in portraiture.

O’Keeffe is redeemed in earlier works that highlight her unorthodox color palette, blank spaces, organic forms and deliberate brushstrokes. “Blue Hill No. II, 1916,” is flooded with a deep blue hill and a greyer blue sky that recalls other water works. An uneven circle of blank paper is directly to the right of the top of the mountain, as if the sun is moving in the background. Her visible brushstrokes add a rough texture. She lightens her hand in the red and pink tie-dye of “Sunrise,” from 1916. Radiating from the emerging yellow sun, her colors unapologetically bleed into each other with a fond warmness. The artist painted and drew undisturbed scenes of nature that leaned into her own process of feminine understanding as it related to her environs.

Preferring the countryside to the city, O’Keeffe found solace in the study of new environments. She believed her New York audience was incapable of slowing down enough to appreciate her works for what they were. Those who paused imbued them with their own meanings rather than accepting what was in front of them. They made a spectacle of everything. O’Keeffe advises her viewers to slow down, to observe and to wait. Her attention to her subjects, and her love for them, is only visible to the viewer who takes time to understand that, because while they may see beauty they will never see it as Georgia O’Keeffe did.

The exhibition is on view from April 9 through Aug. 12. NYU students can book complimentary affiliate tickets here.

Contact Julia Mejia at [email protected]