Review: ‘Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You.’ is all too relevant in a post-Roe era

Barbara Kruger’s newest exhibit is the most commercial, anti-capitalist exhibition about power dynamics and bodily autonomy.

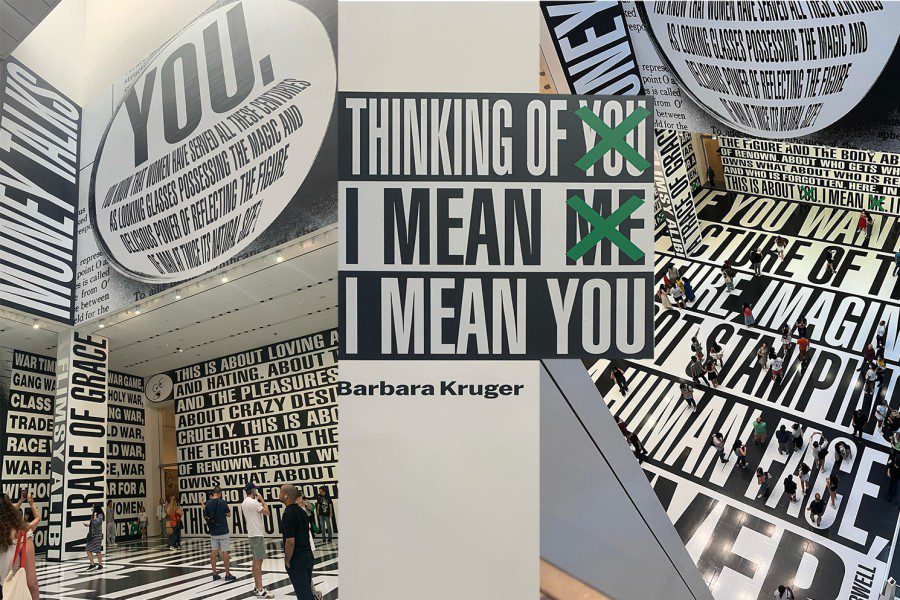

Barbara Kruger’s latest exhibition is on view from July 16, 2022, through Jan. 2, 2023. (Natalia Palacino Camargo for WSN; Max Mimaroglu for WSN)

September 19, 2022

Barbara Kruger’s “Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You.” demonstrates her profound influence beyond the art world as a conceptual powerhouse. Within the art exhibit, the viewer is transported into a monochromatic reality that purely relies on the strength of Kruger’s words that she styles through overlaid text. This show showcases Kruger’s status as one of the most influential artists of the 20th and 21st centuries. Despite being in the art world for the past five decades, Kruger’s conceptual and collage work is still relevant in defining the voice and aesthetic of a whole new generation.

While Kruger is known for using found images, black-and-white photographs and white-on-red Futura bold text, her latest exhibition displayed at the Museum of Modern Art is a breath of fresh air. Despite abandoning her signature red font for black and white, it is impossible not to recognize her signature bold Sans Serif textual statements. Kruger’s words envelop the Donald and Catherine Marron Family Atrium at the MoMA, with printed vinyl covering the floors and walls.

The layout of the exhibition allows viewers to be part of the space as they walk over vinyl and provides multiple points of view throughout the museum’s floors. While viewers might be cautious about first stepping into the installation, not wanting to ruin the floor, the true meaning of this work only comes to life when the purity of the gallery is disrupted. On view from July 16, 2022, through Jan. 2, 2023, Kruger’s latest show shares compelling ideas of power and desire that ring more relevant than ever in the wake of a post-Roe v. Wade era.

Kruger’s feminist and anti-consumerist work appeals to the public through irony, addressing the evils she fights in their language. Her typical work uses sensational and authoritative language, such as her famous “I shop therefore I am” (1987) and “Your body is a battleground” (1989), which was created for Washington’s 1989 Women’s March and has regained popularity after the overturning of Roe vs.Wade.

Before the opening of Kruger’s recent show at the MoMA, she responded quickly to the reversal of Roe v. Wade with a bold art piece that stated, “If the end of Roe is a shock, then you haven’t been paying attention.” Similarly, her current MoMA installation reflects on the state of the world by engaging with ideas of power and agency.

Her provocative use of directly addressing the viewer and bringing them into the piece is what effectively exposes the power dynamics, not only between artist and viewer but mirroring that control of the body, identity and consumer culture. Her use of direct language — such as plastering on a wall in monumental size the word “YOU” — confronts the viewer. As a result, the exhibition feels like an intimate conversation with the artist, as if we are reading her thoughts. This is especially true since some of the words are crossed out as if the thoughts were in transit and edited, such as the show’s title, “Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You.” Other provocative phrases of direct address that transmit this feeling of intimacy and desire are “The moment pride becomes contempt. About wanting one another. About fearing one another. About touching one another. About the war for me to become you. I mean me. I mean you.”

Regarding doom and cynicism, Kruger borrows language from Virginia Woolf: “Women have served all these centuries as looking-glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size.” Although Woolf’s words originally had a different context, they remain relevant given the recent laws exerted over women’s bodies.

The curation and text of the work transform the viewer from a participant dominated by this vast space to an omniscient power throughout their visit to the MoMA. Playing with “relationships can expand to considerations of inclusion and exclusion, dominance and agency” as the curatorial text describes.

Contact Natalia Palacino at [email protected].