John McEnroe and the Sport of Cinema

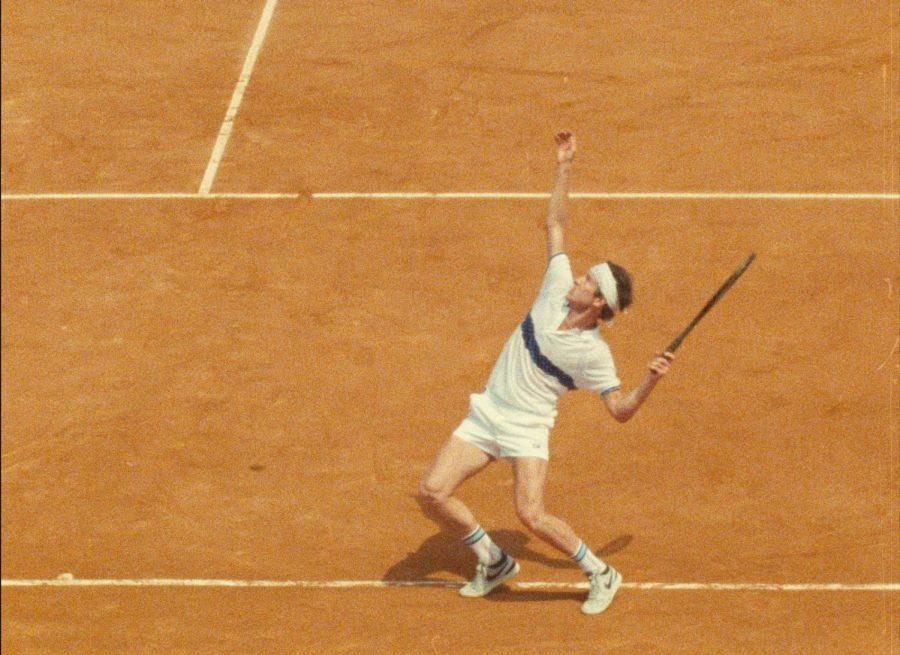

Courtesy of Oscilloscope Laboratories

“John McEnroe: In the Realm of Perfection” is now playing at the Film Forum.

September 4, 2018

“John McEnroe: In the Realm of Perfection” is not a documentary about the tennis extraordinaire. Instead, it is a meticulous exploration of the game of tennis through the eyes of a filmmaker. McEnroe, whose notorious short-tempered personality led him to triumph numerous times at the U.S. Open and Wimbledon, was never able to raise the trophy at Roland Garros. But in 1984, he came as close as he ever would.

With mastery, writer and director Julien Faraut crafts a picture that surpasses typical sports documentaries by postulating how McEnroe’s tennis, and the overall game, is an art form parallel to cinema itself.

The majority of the documentary is composed of archival footage from McEnroe’s run at the 1984 French Open, shot on 16mm film by Gil de Kermadec. Kermadec was a creator of instructional tennis films before choosing to document professional players in a series of portraits — his final project was McEnroe. Faraut reproduces de Kermadec’s fascination and seamlessly weaves these clips into artistic movements. Doing so, he demonstrates an appreciation for both the sport of tennis and for McEnroe’s own dedication to perfection.

The original footage bears an intimacy that grounds the viewer only in the tennis — it is as if time stands still and the audience is forced to shift its energy to the game in front of them. Watching McEnroe becomes like watching an auteur of a film. He dictates everything, from the length of the rallies to the direction of the ball. His style and match play also lends itself to a theatrical performance; yet, unlike an actor who takes on a fabricated role, McEnroe depicts nothing but the truth.

“Cinema lies, sport doesn’t.” This quote by Jean-Luc Godard opens the film and is revisited by Faraut throughout the narrative. Sport is black and white — you can only win or lose. There is no room for deception because success and failure are distinctly separated. From Faraut’s perspective as a filmmaker, the analysis of McEnroe’s game allows him to produce a documentary that portrays cinema in its purest form. All that is presented on the footage is the story unadulterated by fiction.

In the history of tennis, John McEnroe is an anomaly. He is filled with a rage that would consume and devastate other players, but spurs him on to play at the zenith of his ability. The documentary shows many instances of McEnroe combating with the chair umpires over questionable line calls. These serve not to highlight McEnroe’s short temper, but to display his drive for a perfect game. This drive, Faraut argues, is found in cinema and is the backbone to an artist utterly devoted to their craft.

Tennis falls outside the usual realm of athletics; it is a solitary game, and Faraut concludes that it is most often a battle against one’s self rather than against one’s opponent. With “John McEnroe: In the Realm of Perfection,” Faraut offers a compelling and rare thesis that McEnroe is an auteur of the court whose quest for perfection mimics the diligent process of cinema.

“John McEnroe: In the Realm of Perfection” plays at the Film Forum through Sept. 4.

A version of this article appeared in the Tuesday, Sept. 4 print edition. Email Daniella Nichinson at [email protected].