The Long Lost Letters of Sylvia Plath

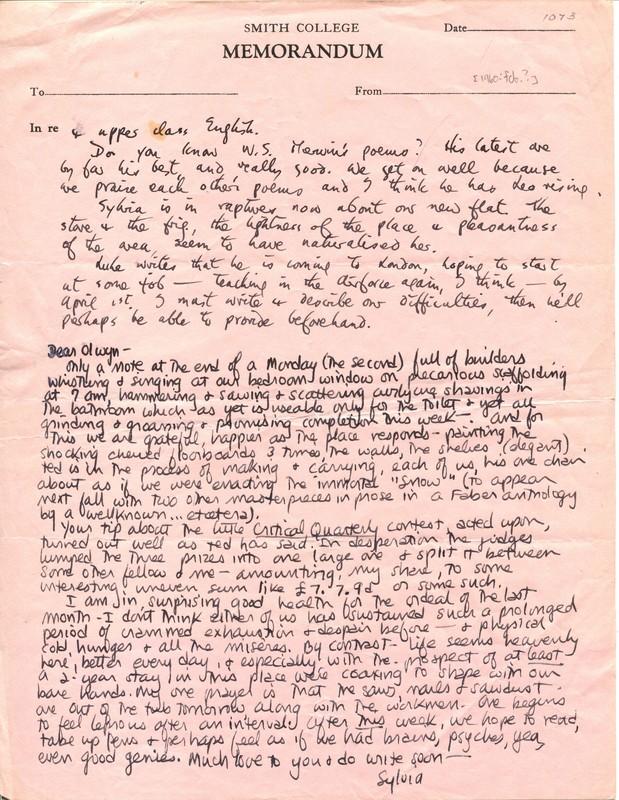

One of the many lost letters published in “The Letters of Sylvia Plath.”

April 11, 2018

On Sunday morning at the 92nd Street Y, an eager crowd gathered to hear Karen Kukil, associate curator of special collections at Smith College, and Peter K. Steinberg, a Sylvia Plath scholar, deliver a lecture on the two-volume edition of “The Letters of Sylvia Plath.” Ted Hughes, the late husband of Sylvia Plath, had previously only allowed the publication of selected letters, but this was all about to change.

In the newest edition of Plath’s letters, Kukil and Steinberg worked tirelessly for years to put together a collection of every existing letter from Plath that they could find. The mind of Plath, who never left a letter unanswered, comes alive through this collection of lost correspondences. They illuminate us to her most intimate and thoughtful musings and surface some of her work’s untapped ideas.

“All the deleted words and wicked comments are present [in this collection],” Kukil said to the crowd.

For an event at Smith College not too long ago, the organizers invited recipients of Plath’s letters to recite passages from her letters to them while Kukil and Steinberg continued to compile a new edition of her letters. While only the first edition has been released, it contains letters she wrote in college up until she met and married Hughes.

Plath wrote in different voices to entertain her friends. The new edition brings to the fore her thoughts on poetry, literature, history, politics, religion and her aspirations as a woman and a writer.

“We wanted to give Sylvia Plath the chance to tell her own story, in her own words and at her own pace,” Kukil said.

Kukil and her students started by transcribing around 168 letters in Smith’s special collections.

“I had a full head of hair when this project started,” Steinberg said.

He used to spend nearly 12 hours on weekends and about one or two hours every single day for four years transcribing these letters. The two volumes have over 1,400 letters of Plath’s. Kukil stated that when the manuscript was sent to the publisher, it was 3,300 pages long with nearly 3,600 footnotes.

“And then we held our breath,” she said.

The letters humanize Plath and helped to validate her literary prowess. None of her spelling mistakes or syntactical idiosyncrasies have been omitted. The word, “lavender,” Kukil and Steinberg said, was often throughout her letters.

Kukil and Steinberg aim to change the perception of Plath among readers.

“I found how human she was,” Steinberg said. “Dying is an art, living is an art, and she did it extremely well.”

Plath wrote her letters with the same intelligence and artfulness with which she approached her poetry. Perhaps it was because she had wild dreams of seeing her correspondences published one day. At one point, she asked Ted Hughes to date her letters in case people would want to read them in the future. In one of her journals, Plath wrote these were “the intimate thoughts of a girl meant for publication,” and it seems as though her voice has finally been heard.

Email Devanshi Khetarpal at [email protected].