NYU Professors at Horizons Conference Share Psychedelic Research

Should psychedelic therapists be required to try their own medicine? NYU professor Elizabeth Nielson brought up the issue in her talk at the annual Horizons Conference held at Cooper Union on Oct. 6-8.

October 13, 2017

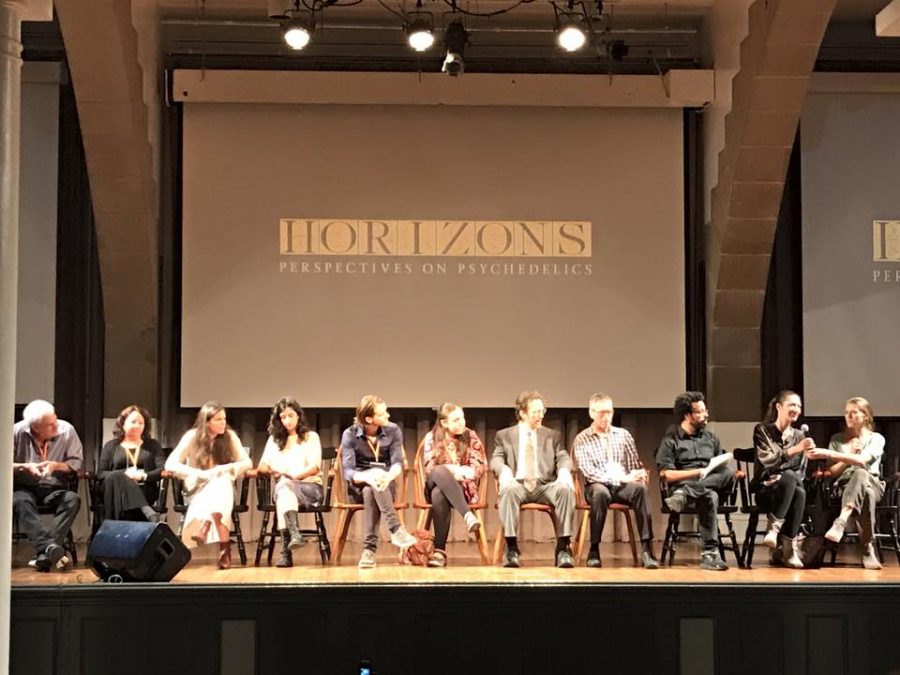

Three NYU Professors shared mind-altering information at Cooper Union last weekend during the annual Horizons Conference — a forum that discusses the use of psychedelics in science, medicine and society.

Research Professor of Psychiatry Michael P. Bogenschutz, Therapist in NYU School of Medicine Psilocybin-Assisted Treatment of Alcohol Dependence Holly Duane and Psychologist in the Department of Psychiatry Elizabeth Nielson all made the short trek from NYU. Both Duane and Bogenschutz spoke about their recently published experiment, a “Double-Blind Trial of Psilocybin-Assisted Treatment of Alcohol Dependence,” through results and patient testimonials. Nielson’s talk, on the other hand, covered a topic that most psychedelic therapists fail to address: should psychedelic therapists be required to try psychedelics?

Nielson’s talk was based on a manuscript she co-wrote with Jeffrey Guss, another Clinical Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at NYU, about the perspectives on the therapeutic process in the use of psilocybin, the chemical found in psychedelic mushrooms, in therapy. The manuscript, as well as Nielson’s talk, emphasized the need for first-hand experience research for therapists when it comes to psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy.

“During the 1950s a lot of researchers cited their own experience with psychedelics as experience for their work,” Nielson said during her talk. “It was something that helped them prepare for their work, and even something they considered a requirement for becoming a psychedelic therapist.”

Since the 1950s, however, the United States has introduced the Drug Enforcement Administration, which has led to an extreme increase of restrictions on drug research.

“Psychedelic therapy is now held to the standards of efficacy of other pharmaceutical drugs and needs to produce the same results in double-blind trials,” Nielson said. “The problem is that psychedelic therapy is a poor fit for randomized controlled trials because RCTs exist to isolate substances that are prescribed from any psychosocial effects or extra pharmacological effects, which is kind of antithetical to how psychedelic therapy works.”

While the results of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy can be measured in numbers, many other factors that are subjective to each patient also contribute to these statistics. Not only are patients’ attitudes, moods and actions changing, but so are their perspectives, which do not correlate well on a chart. As a result, it can be challenging to draw any concrete conclusions from these results.

Nielson said that psychedelics are considered to be a schedule one drug, which makes it increasingly hard for therapists to openly discuss usage in an academic setting because schedule one substance is defined as a drug with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

“The legal status of these compounds further complicates this problem because we cannot ask therapists if they’ve had outside of sanction training experiences,” Nielson said.

Guss said in an interview that the lack of conversation surrounding direct therapist experience is the biggest problem of all and that he thinks there is a need for both sides of the dialogue surrounding psychedelics in medicine to be openly discussed and researched.

“Objectivity is an important part of Western research and remaining in an objective position is of value in the kind of research we’re doing,” Guss said. “However, many people believe that you cannot be a psychedelic therapist without having the experience, or else they are inadequately trained.”

Along with this lack of conversation, there is an inherent lack of research on the topic. No experiments have been conducted to see whether experience in psilocybin therapy helps psychologists better care for their patients, which is the most important factor in any kind of therapy.

Nielson said that the best way to moving forward is to begin the conversation and allow research into the rapidly expanding field of psychedelics.

“The best methods for training should really translate to the best outcomes for treating patients,” Nielson said during her talk. “Providing quality care, quality treatment and healing is top priority.”

Email Kristina Hayhurst at [email protected].