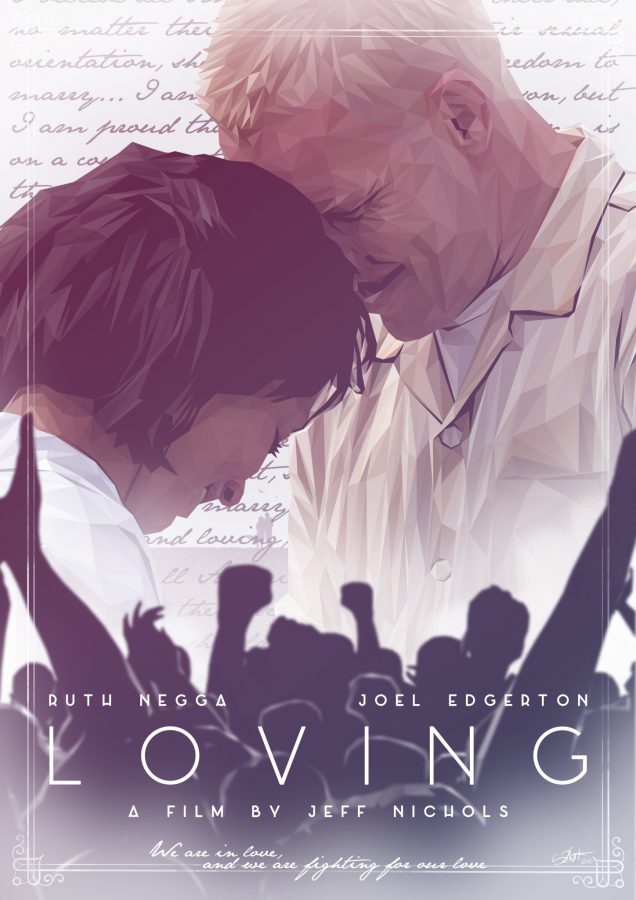

‘Loving’ Proves Comforting in Its Justice

Directed by Jeff Nichols, “Loving” portrays the story of an interracial couple during the case of Racial Integrity Act of 1924.

November 4, 2016

In a momentous case in 1967, the Supreme Court case of Loving v. Virginia ruled that the Racial Integrity Act of 1924, which prohibited interracial marriage, was unconstitutional. “Loving,” the new film directed by the acclaimed Jeff Nichols, paints a very emotional and real view of the case through the eyes of the interracial couple, the Lovings, who filed the suit.

Coming right off the edgy drama “Midnight Special,” Nichols shows a consistent theme throughout his films. The projects each involve isolated individuals dealing with people who fear what they don’t comprehend.

Richard Loving (Joel Edgerton), a white man, and Mildred Jeter (Ruth Negga), a Native American and African American woman, were married on June 2, 1958 after learning about Jeter’s pregnancy. There is little fear between the couple of getting married despite the fact that in Virginia at the time, their union was illegal. In the film, the couple is portrayed as blissfully in love with each other. They hardly expect to be thrown in prison for their marriage.

Richard in particular maintains that “they aren’t hurting anybody” by getting married. This argument was used during their Supreme Court hearing. The argument is just part of the simplicity in content throughout “Loving” that emphasizes the love between Richard and Mildred in a very sweet and sincere way.

As far as acting, both Edgerton and Negga give astounding performances. Edgerton establishes Richard as a kind-hearted simpleton who loves his wife and family dearly, whereas Negga forms Mildred as strong and determined. Even the Loving’s only remaining child, Peggy Loving, was astonished by the raw emotion the actors were able to portray.

It was hard to watch these two stunning performances compared to the acting from Nick Kroll, who plays ACLU attorney Bernard Cohen. Cohen and Kroll share a strong physical resemblance, but unfortunately, Kroll was a miscast. His uneven performance was extremely distracting in all of his scenes.

Moreover, the other supporting performances were more than competent. Although Michael Shannon was only in a few scenes, he shined as the photographer responsible for the case gaining attention around the United States. The actors who portray Mildred’s family members were unknown and were chosen to give a more realistic vision of the community in Virginia that the couple resided in. All of them gave fantastic and memorable performances, despite their smaller scenes.

The film’s cinematography was one of the strongest features of the whole project. Every shot was gorgeous and perfectly framed. Set in rural Virginia as well as the streets of Washington, D.C., cinematographer Adam Stone, who has worked with Nichols’ on all of his biggest projects, used the beauty of his surroundings to show the drastic differences the couple felt in place. The filming particularly emphasizes Mildred’s deep connection to the fields of Virginia, giving a sincerity to the story that would certainly have otherwise been missed.

Without much dialogue, it is astounding how effective and powerful the film was. Its direction, acting and cinematography alone are able to carry the entire story. Instead of clouding the plot up with conversation, the powerful story of injustices duly overturned shone through.

Email Sophie Bennett at [email protected].