SXSW: The Long, Twisted Journey of Fantastic Negrito

Fantastic Negrito is releasing his debut album “The Last Days of Oakland” on June 3 via Blackball Universe.

March 28, 2016

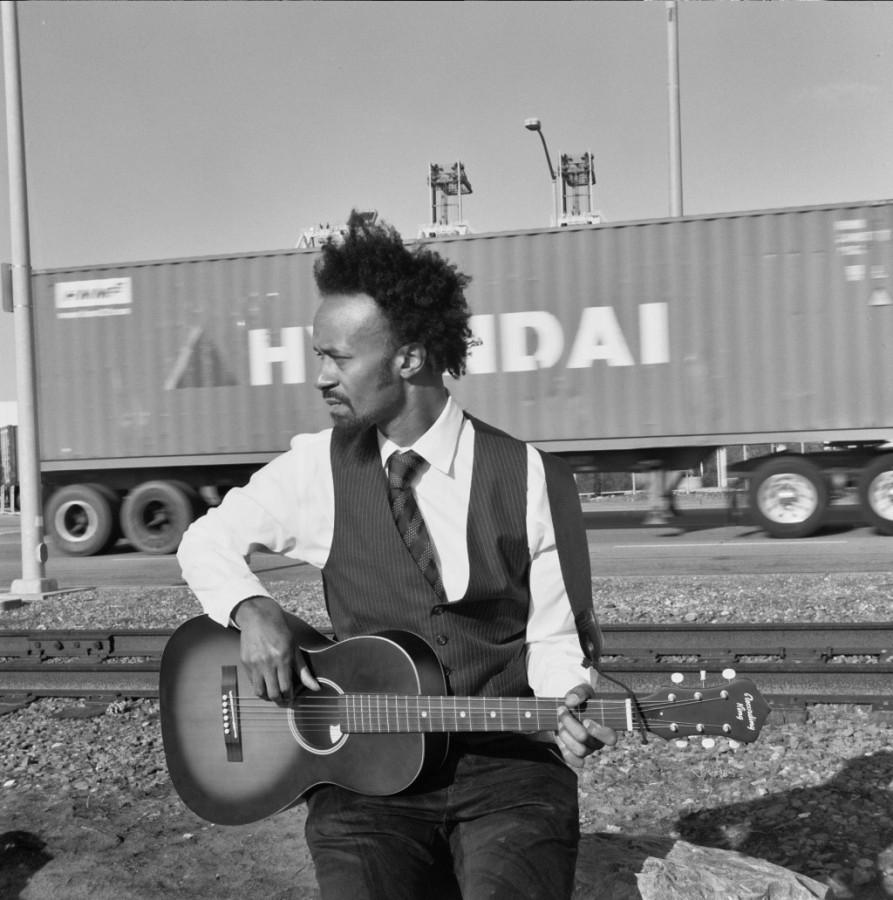

Not many people can say they’re working their way into the music industry for a second time, let alone a first. But Fantastic Negrito — whose real name is Xavier Dphrepaulezz — and his past could rarely be described as normal.

After a record deal with Interscope Records 20 years ago came apart and a car crash put Dphrepaulezz into a coma, the Oakland, California native took a few years off to reevaluate where things stood in his life. Now, he’s reinventing himself into the blues-rock mold (although he hates the idea of genres) and is doing his best to represent the city in which he grew up. After putting a few songs out over the last couple years, Fantastic Negrito is finally releasing his debut full-length, “The Last Days of Oakland,” this June — and he’s certainly not afraid of who he offends in the process.

WSN sat down with Fantastic Negrito at South by Southwest a couple weeks ago to talk his upcoming album, his NPR Music debut and punk rock churches.

WSN: You won the first Tiny Desk concert contest last March with your song “Lost in a Crowd.” Can you talk to me about how that song came together and from where you drew the inspiration for it?

Fantastic Negrito: I drew a lot of inspiration upon writing songs like “Lost in a Crowd” and “Night Has Turned To Day” just from playing off the streets. I thought that the best place to get inspiration or to test out ideas was to play them for people who weren’t really interested in hearing them. So I’d go to the train station, in front of a donut shop. And then I’d see if I could make that connection and get people engaged and involved. So that’s where a lot of the songs came from, it was extremely organic.

WSN: Winning that contest, you kind of became a sensation almost overnight. What was that like?

FN: I couldn’t play street corners anymore, which I really miss. But it was very gratifying and very humbling and I feel indebted to NPR Tiny Desk and Bob Boilen, he’s an amazing guy and a beautiful human being. It was an interesting part of the journey, and it kind of put the Fantastic Negrito project on steroids. It was very exciting. It was great for the Bay Area, great for the city of Oakland.

WSN: You’ve kind of had an atypical path through music. You had the record deal with Interscope 20 years ago which fell through…

FN: You weren’t even born! But I feel like it’s good for everyone, you know, just keep on moving. Don’t listen when people tell you that you can’t do something. Walk towards the light and walk towards the truth because even in your 40’s, what you’re trying to say as an artist can resonate with people.

WSN: And then you had the car crash and you thought you were never going to play music again.

FN: I have a saying: take the bullshit and turn it into good shit. That’s kind of the way I’ve lived my life. There’s been many obstacles I’ve faced growing up as a young person and I’ve always looked at them as opportunities to rise to the top. And I always looked at bad news that way — whether it was my 14-year-old brother being killed, me being in a coma for three weeks and almost losing my playing hand, failing at a record company. I always looked at them as opportunities to just say “let’s do it now.”

WSN: So you took some time off from music. Was there a moment where you thought “I need to be playing again”?

FN: There was a moment. I decided to have a child, which is amazing. And one day I couldn’t put him to sleep — he was about 11 months old. I had sold all my equipment and I just had one old guitar that was underneath this orange loveseat in his room (don’t ask me why he had an orange loveseat in his room). I looked at him and I looked at the guitar and I thought “this thing is funky and out of tune,” and I grabbed it and I just remember playing like a G major chord, and he just freaked out. So many emotions hit me at that point and I thought, look at this guy. He doesn’t know anything about the politics of music, or the ups and downs and disappointments and accomplishments of life. He’s just a baby and he thought that G major was amazing. And that began a slow walk back towards music.

I’m in a collective called Blackball Universe, and they encouraged me and we helped each other, and finally I came up with the idea of Fantastic Negrito. I remember this one intern was like, “Xavier, white people don’t like saying negrito! We’re not comfortable with it.” And I thought was hilarious, and i thought that’s what’s wrong. What have we done to each other where we can’t talk to each other anymore? So I thought then it’s even a better name if it’ll let people talk to each other.

WSN: Does it feel different this time around, now that you have this host of experiences under your belt and you’re also 20 years older?

FN: Yeah it does feel different. I know who I am, and I can kind of rein in the monster, the narcissist, exhibitionist crazy person. I don’t think I could have done it [when I was 20]. I think I messed up a couple good opportunities. Some things should just be harvested when they’re ready. I hadn’t lived enough, I hadn’t failed enough.

WSN: The new album is kind of all over the place…

FN: Man, they always say that to me! I’ve been trying to entertain that since day one.

WSN: In a good way! In terms of the topics you touch on and the sounds you work with, you work in blues, some gospel and tinges of punk all over the place.

FN: Oh yeah, I’m a fan of that. I always feel like when music is blues-ish but it has that punk gospel kind of edge, I love that.

WSN: So where do you draw that inspiration from?

FN: I always feel like Fantastic Negrito concerts are kind of like church without the religion. I draw it from black roots music — that’s a good name for it because it’s really the music of my grandmother and that generation. And if you’ve never been to a black church, you’ve gotta go to one. It’s that energy of punk rock. It’s intense and it’s spiritual and I like to draw off of that.

WSN: The new single, “Working Poor,” touches on a lot of issues that are especially pertinent of Oakland. That income equality and people not being able to pay their rent. How have you seen that develop over time, and why do you think it’s important for you to sing about these things?

FN: Well when I say “The Last Days of Oakland,” I mean it in the sense of thinking, “that era is over, that was the old Oakland.” All the inner city things have changed. Now we have the opportunity to collectively do something new. And for me that’s exciting.

As far as working poor, I think we live in a time where people are working harder than they’ve ever worked before, but they’re making less than they’ve ever made before. And I think that it’s probably unprecedented in the history economically of this country where such a small amount of people control all the wealth. Working class people who are working 40, 50 hours a week and are just making it — it’s not the America I imagined as a young person. And I think we’re better than that.

WSN: Do you think there’s a way for us to find that middle ground of innovation that doesn’t push people from their homes?

FN: I think we better. If we don’t, it’ll all crash. And we all need each other in this human family. One thing I’ve learned, it’s how much we all really need each other and we’re all connected to each other. We have to reject greed. I’m sorry it’s so simple, but if we can reject greed and think collectively, that’s what I try to embrace. I don’t pretend to have the answers for everybody.

“The Last Days of Oakland” is out June 3.

A version of this article appeared in the Monday, March 28 print edition. Email Alex Bazeley at [email protected].