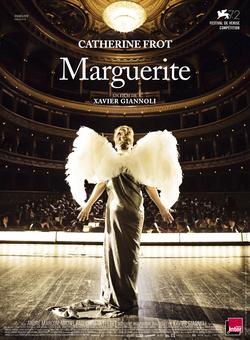

“Marguerite” is a Surprising, Off-Key Delight

Marguerite tells the story of Marguerite Dumont as she follows her love for singing, while lacking the talent.

March 8, 2016

In the film “Marguerite”, director Xavier Giannoli explores this question: What do you say to a person who obviously has a very strong passion for something, but lacks the talent?

The French film opens on Paris in the 1920s, as an audience is escorted into an exclusive benefit concert put on by, and in the home of, the great Madame Marguerite Dumont (Catherine Frot). Before being officially introduced to the mysterious baroness, the audience first meets her through her lavish and gaudy home and decor. When she finally arrives, Marguerite is preparing for her grand entrance, anxiously waiting for her husband to return home. Deciding to go on without him, the baroness takes her place in front of the crowd. The film then cuts to a scene where we are introduced to the husband, Georges Dumont (Andre Marcon). Georges is on his way home, when he stops his car, gets out and opens the hood to rub motor oil all over his hands.

Back at the Dumont mansion, Marguerite begins singing. Expecting to hear the majestic and powerful sound from the opera singer; instead, there is screeching, bellowing and a lot of howling. Alas, the great and mysterious Marguerite Dumont is tone-deaf.

The rest of the film focuses on all of the people who contribute to the grand illusion that the diva can sing. While she is quite fervent about music, this passion is only pursued in order to fill emptiness within her. Georges is ashamed, no longer thinking of Marguerite as a person but instead as a freak. She in turn is crying out for his attention, much like a small child does for their parents. And in a way, Marguerite is just that — an elderly child. Her childlike innocence and naivete are what enamor all who meet Marguerite and what keeps these same people from revealing the harsh truth that passion doesn’t necessarily translate into talent.

The film is carried by Frot’s portrayal of the complex and wildly lovable character of Marguerite. The actress has actually been studying singing for years, so one could only imagine how much work it took to butcher her voice to create the worse than nails on a chalkboard sound of the baroness.

The film is ultimately a delightful surprise. “The sublime and the ridiculous are never far apart,” as a character points out when introducing Marguerite before a performance. The best part of “Marguerite” is the way it tackles this relation between harmony and dischord. This relation is not only literally shown in Marguerite’s lack of pitch, but also in the relationships that she forms with others. The 1920s were a time known for the rise of both artistic and personal freedoms, which is why this idea of the sublime is often brought up in the film. Marguerite’s singing, though horribly off-key, is beautiful in its own right — beautiful in the way that the audience is flushed with emotion because of the way that Marguerite bears her soul for all to see.

The film will open in New York at the Angelika Film Center and the Paris Theater on Friday, March 11.

Email Dejarelle Gaines at [email protected].