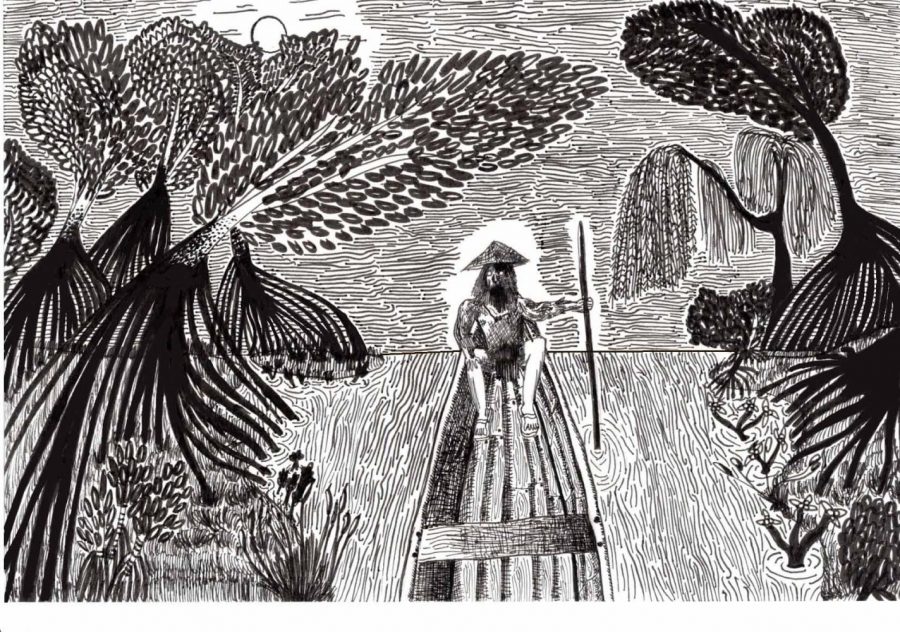

The light shines behind him now. The boat moves towards darkness. The music at his back gets fainter the further down river he goes, the warm yellow of the houseboat fading, replaced by the silver of the moon. The water is tepid, the current lazy and he moves slowly through it. The light on the ripples shimmers along the way.

Once he moves into the marsh proper, he expects pitch black. But even the mangroves, branches knotted as they are, can’t shut out the light of the high moon on the river. Every few yards the light pierces the leaves, leaving patches of water sparkling like beacons. It’s beautiful, he thinks.

“Open your eyes.”

The captive wakes with a start, but the gag in his mouth keeps him quiet.

He squirms on the floor of the canoe, like a floundering trout, but manages to put his hands on the prow. He tries pushing himself up to sit, but his arms are bound too tightly. The ropes are coarse and his wrists are raw. Feebly, his palms scrabble around on the splintered wood, nails scraping against chipped paint.

The gag stops his teeth from grinding.

After a soldier’s limit of exhaustion, he stops struggling. Resting against the plank opposite his kidnapper, he tries to look at the man rowing the boat. But the leaves no longer part for the light, and the only things shining are his captor’s tombstone shaped teeth.

The man chuckles, his laugh whistling through the gaps.

For a while, the captive looks at his captor, his wet eyes sparkling in the light. His captor’s eyes are shaded by a farmer’s hat. The moonlight doesn’t fall on them.

“Have you ever been here before?” he asks. “It’s quite far from where I usually work, but it’s practically next door to where I found you.” Southerner.

“Oh, don’t give me that look, Uncle Phan. It’s practically painted onto your face,” he leans back and crosses his legs. “I don’t play sides. Now enjoy the scenery.”

The captive peers over the edge of the boat. The canopy is denser now, the sky is thick with leaves. The moon falters, turning the water dark. He looks over his shoulder. Fireflies sparkle above the water, flitting yellow and green, in and out.

The other man chuckles at the captive’s darting eyes, exposing small, pearly teeth shoved into blood-red gums. “I keep coming back to this place,” he says wistfully. “A man in my profession, why do you think I risk it?”

The gagged man refuses to make a muffle, disappointing his captor.

“Fine, Uncle Phan,” he sighs, arms crossed. “Do you know why you are here?”

Phan looks down at his bindings. When he raises his head, a rictus grin confronts him.

“My name is Diêm Vương.”

Then a shaft of moonlight catches his captor’s face. From within sunken sockets, the eyes glow.

The one-sided staring match ends. Lieutenant Colonel Phan Anh Chiến blinks. The captive’s tear-swollen eyes reflect his knowing mind.

“Now,” the captor grunts, reaching under a tarp at the back of the canoe’s stern. “Eat this.”

He thrusts a chipped bowl in front of the colonel’s gagged mouth, half full with old rice. Atop the fading white of the grains lay three coins. Three men in farmer’s clothes stare out of the metal. The chopsticks stand erect. The gag is wrenched open and the bowl tipped into his mouth.

“For your health.” Rice is shovelled down Phan’s throat.

“For your wealth.” Phan almost chokes on the coins.

“And for whatever else you need in the afterlife.” The chopsticks are shoved between his teeth, the gag pulled tight from behind, causing his jaws to slam shut against the pieces of wood.

Phan reels. He doubles over with hacking coughs, hard rice and copper threatening to seal his throat. Through heaving breaths, he forces himself to swallow, only to make the rawness of his throat painfully apparent.

Left gasping through the gag, Phan’s coughing fit is interrupted by his captor throttling him to attention.

“I wouldn’t do this for just anyone, and certainly not for any Northerner. But I figured a Trung tá (Lieutenant Colonel) deserves this humble agent’s best.” The man stands up now, bending over to dig under the tarp. “It might be homelier than you’re used to,” he says, throwing out rusted ration tins.

“There’ll be no coffin.” A rag is tossed on the floor.

“There’s no music.” He sets an assault rifle down on the plank he sat on.

“And there’s no incense.” A cardboard box is removed.

“You can’t have everything,” the man shrugs, turning to face Phan, “but at least you get your blanket.” He removes the lid of the box. The white sheet unfolds with a flourish.

Stepping around Phan, the captor drapes him in the cloth. He wraps it around the binds, the arms, legs and chest. The extra cotton he double-knots behind Phan’s back. He hauls the body up by the knot, propping the cocooned figure on the boat’s edge.

The boat stops as he jams the oar into the river bed.

He places his sandal on his captive’s chest and points the rifle between Phan’s eyes. He leans in and whispers.

“I’ll be sure to buy you a funeral song on my way back.”

And now, the tears fall. They fall in rivulets and then in rivers. They fall like Phan’s spirit. They stain his cheeks with the past.

His command. Iron like a fist or an anchor. His men. War-weary but tunnel-ready. His family. Who wait and will wait. His country. Halved, like a jackfruit. Exposed to foreign flies.

They are all now past.

He cries their tears for them. He cries his tears for himself.

His life falls down his face. A farmer’s son slides down the bridge of his nose. A college graduate — witness to serenity in immolation — droops over the corner of his lips. A guerilla who squats in the muck hangs off of his chin.

He tastes the salt, the wetness. Phantom blood coats his tongue. He cries his past lives away.

Before he hits the water, Lieutenant Colonel Phan Anh Chiến looks up at the sky. It is open again, and his tear-stained face shines silver.

The only witness is the moon’s milky eye.

Email Nicholas Dharmadi at [email protected].