Now I saw when the Lamb opened one of the seals and I heard one of the four living creatures saying with a voice like thunder, ‘Come and see.’ And I looked, and behold, a white horse. He who sat on it had a bow; and a crown was given to him, and he went out conquering and to conquer.” — Revelation 6:1-2

Pestilence rode his canary yellow Beetle into Baltimore. He strummed his fingers on the driving wheel along to big brass funk. He needed to feel the flow of the music. When he’d chosen his small Baltimore corner room, he’d selected one with enough room for pacing.

Pestilence spends more nights these days driving rather than walking. He doesn’t sleep — none of the horsemen do — just occasionally close their eyes and lay down to remember. They don’t need sleep, food or any other vices; if they partake, it’s out of curiosity. Pestilence, for example, was very satisfied with caviar and was disappointed when the number of egg-laying sturgeon dwindled. He wished he’d eaten more caviar when he’d had the chance.

Hunger was the largest obstacle keeping him from enjoying his food. The sensation kept him awake at night, and before he bought his Beetle he would walk through the streets for a few final moments, just craving, before moving on to the next city. The Horsemen were not the sole cause of every misfortune in the world. Sickness, hunger, war and death were things they had some control over, sure, but for the most part they were simply drawn to naturally-occuring tragedies.

Livestock was Pestilence’s strong suit, and on rare occasions, a disease that festered in bovine brains would creep into the human organ lining. This grim exchange happened through food, naturally.

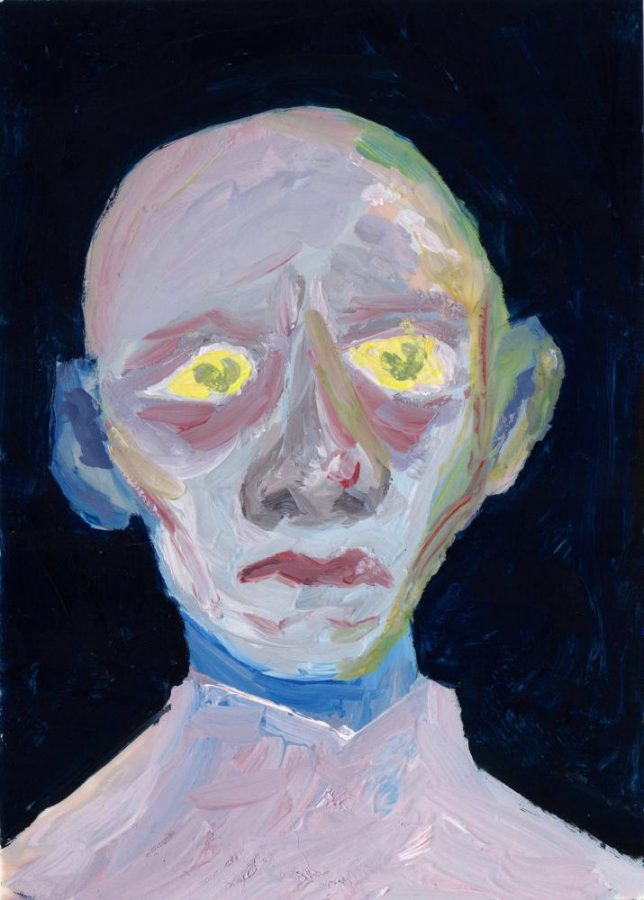

He spent most of his time in Africa, observing the deterioration of a small village in the Congo. He sat on a throne of rotting hippos and observed from the outskirts. No one seemed to notice the sickly man with the frayed hair, green eyes and speckled skin ripping open roadkill. No one was awake to see him peering into the window of a house with a red X painted on the door.

He saw a python kill a small elephant there, by the village. He wrote it down on an ancient text he’d stolen from Alexandria and since used for personal notes. The python made it onto his list of “Things I never thought I’d see.”

He’d never thought he’d see a catapult rain down thousands of severed heads on a besieged city. He’d forgotten seeing a slave ship captain burned alive along with ship, crew and rebellious cargo. “It must have been when I was walking back from Morocco along the coastline,” he thought. Then wrote that he’d seen an elephant strangled by a python today.

He watched out for the python slithering through the grass. It never killed another elephant but plucked unsuspecting birds from the sky. After a week passed with no python sighting, he investigated its usual jungle trail. He found it coiled up around its nest, shriveled from disease. The eggs in the nest were unhatched. Pestilence considered raising a family of snakes. He decided against it and buried the eggs with their mother.

Due to his nomadic nature, Pestilence only kept his journal and a silver crucifix plucked from the neck of a priest who had died from exposure to his patients. The plague made no exceptions for doctors. Pestilence had never talked to him, but he took the crucifix before the graverobbers could.

His only other possession was an apple from the tree of Eden. A black oil rubbed off on his hands when he held it, and he worried that if he squeezed too hard it would explode. He kept the apple in a ziplock bag as a precaution.

One day, while Pestilence sat on his carcass throne with his head on his fists, a flurry of white vans drove into town. Men in hazmat suits poured out and scoured the town for the dying and dead. Pestilence was no stranger to doctors, but he perked up when he smelled shampoo. Shampoo is an odd odor in a ghost town. It wafted out of a tear in one of the doctors’ suits. He stared at this woman, who was preoccupied with her patient. Her coworker noticed, and in the ensuing panic, Pestilence was pushed into the van with this woman as she was rushed off to the nearest hospital.

She was chemically scrubbed and showered three times. Pestilence wrote down the shampoo brand. Eventually, she was cleared to fly. Pestilence followed her to the airport, and, due to a security guard MIA with the flu, he snuck onboard with little protest.

The doctor coughed and sneezed a few times, but overall she held herself together. Flight attendants started passing out pretzels about halfway through the flight.

“Can I get you something to drink?” asked the flight attendant.

Pestilence scratched the back of his head. “Just some water, please. No ice.”

Pestilence went for more pretzels and saw clumps of hair sticking to his hand. He brushed off the rest of his hair and stuffed it in the empty wrapper. “Bald again,” he said to the doctor sitting next to him. She was too tired to register what happened, only smiled and closed her eyes. Pestilence closed his eyes as well.

When he opened them next, Pestilence was rushed out of his seat by CDC officials. He stood on the tarmac while they covered the plane in plastic. Once inside, he found he’d landed in Baltimore. The airline representative offered to book him on the next flight to the original destination, but he declined and asked for directions to the car rental central hub. Pestilence immediately fell in love with the canary yellow Beetle waiting in the lot. He had no intention of returning it.

Pestilence listened to the radio while he drove into Baltimore City. The feeling of the wheels moving along the road added rhythm and energy to the music, a sense of urgency that emphasized the strumming of the bass and the banging of the drums.

He had visited the United States twice before. The first was on the voyage to Roanoke. He witnessed disease wipe out the entire colony, the survivors vanished into the woods out of desperation. He was stuck there until the next ship came. His utter boredom turned him off of visiting the U.S. for the next couple of centuries.

The second time he returned on a whim after France fell through. The East Coast was more than log cabins now, but he couldn’t shake the dull feeling. He went west. He enjoyed the trek through the mountains, America’s frontier before it was claimed. The only other person he encountered along the way was a member of the Washoe. He told Pestilence to avoid a section of the mountain range that-a-ways; there was an encampment of crazy white people who had shot at the Washoe trying to relieve them of their hunger. He warned him that these people were so mad, they had resorted to cannibalism. “Famine has taken hold of them,” he said. Pestilence avoided them at all costs.

At the end of his long trip, he walked across the desert and arrived in California. He stayed the day, then traveled back the way he came. By the time he made it past the Appalachians, the Civil War had started. He heard about the violence, about men having their limbs shot off by artillery fire. He heard a story from an amputee, half-mad, who was adamant he saw a man on a red horse wielding a flaming sword at Gettysburg. Pestilence again changed course to avoid a Horseman. War was crude.

Now, Pestilence found a place to reside and become reacquainted with the city. Baltimore was a rat town; entire houses built on top of nests, and if Pestilence was inclined one night those rats might wake and carry Baltimore into the sea. That night wasn’t here yet, despite the volume of rats.

Pestilence was driving around Baltimore in his stolen Beetle, again. He parked near the aquarium. Looking up at the great glass pyramid, he decided to pop in. Pestilence had recently read an article about how fish dredged up from the Pacific Ocean had contained higher amounts of mercury than ever recorded. Pestilence tended to avoid the shark tanks. Their teeth were unsettling, and they appeared vengeful.

Leaving the aquarium, a sudden boom shot over Pestilence’s head. He whipped around expecting clouds ripped asunder. Instead, a Navy Ship was entering the harbor for July Fourth. Pestilence composed himself. A tourist next to him puked soft shell crabs into the harbor. Pestilence craved a reminder that the world was not yet on fire, so he went to the hospital.

Pestilence frequented the cafe closest to the hospital because that’s where most people found themselves in the aftermath of diagnosis or death. If it was a diagnosis, they would order everything on the menu, desperate to take in every ounce of life left. If it was a death, they would get ice cream. People only get ice cream when they want to feel like a child again.

Pestilence squinted. A family in the back corner of the restaurant was getting dessert. Pestilence couldn’t make out their expressions, but he could see they were eating pastries. “A family of four,” thought Pestilence. “Maybe a grandmother… but that could still mean a passing. Pancreatic cancer?”

Against his better judgment, he entered the cafe.

The host seated him outside. The cafe faced the hospital’s cancer ward. Pestilence once held a cancerous lung in his hand; it was similar in texture to his apple from Eden. The smell of black tissue wafted from the hospital ventilation and into Pestilence’s nostrils. It was mouthwatering and helped him digest the ham and cheese croissant he’d ordered. He chewed each bite extensively before swallowing, picturing bulbous, cancerous, ruined cells. He went for another bite.

“Pestilence?”

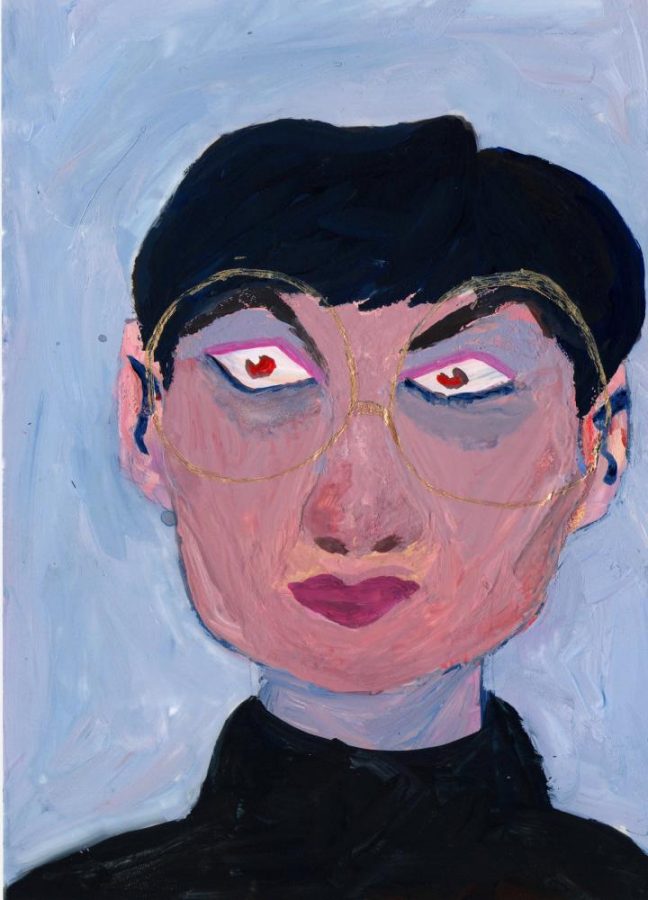

Pestilence looked up and mushy food dribbled from mouth to plate. On the sidewalk across the street was a thin woman. Extremely thin. Her eyes and mouth were too large for her frame, and her head was covered by a bowl of coarse black hair. She wore a dark, black gown. Then, her form flickered. She wore an imperial Persian dress, a Roman toga and a Russian uniform. Finally, she wore a black shirt under a white jacket with matching pants and sharp heels. Famine crossed the street.

Given the day he was having, this made Pestilence very nervous for two reasons:

- The last time Pestilence saw Famine was in the garden of Eden where each Horseman took their respective apples from the tree. Pestilence left the garden after an awkward one-night stand with Famine. He had not seen her since.

- Seeing Famine again after tens of thousands of years was a sign of the world tipping closer to Armageddon, and a reckoning Pestilence did not want.

#

Email Leo Sheingate at [email protected].