Eni Owoeye and I met last spring semester when we both ended up in Professor Robin Nagle’s Environment & Society class, one of the introductory courses for the environmental studies major. I knew nothing, for the most part, choosing to sit in the corner at the front and listen, often, to Owoeye. Quickly, I learned to distinguish her voice and way of speaking from everyone else’s. She sounded deep and steady, her speech well-paced, as if she knew she was taking up the space her insights deserved.

In preparation for interviewing and shadowing Owoeye, I went to Nagle, wondering about her take on Owoeye as a student and a fellow environmentalist.

“She sat near the front of the classroom, on my left and was always present — not just physically, but intellectually and emotionally as well,” Nagle recalled. “She was the kind of student that every professor dreams to teach.”

Owoeye’s experience with education is abundant, to say the least, as she’s never stayed at a school for longer than three years. She’s moved up and down the East Coasts and lived in the South, and, as a consequence, she has witnessed the difference in teaching styles and approaches first-hand.

While at a public school in Texas, she was exclusively taught the history of the state. During her time in Maryland, her teachers got her classmates and her to plant trees by the Chesapeake Bay. While attending a private boarding school in Newbury, Massachusetts, she realized it was the most socially segregated environment she’s ever been in.

Moving to New York for college, however, Owoeye came with the understanding of what all of the different places she studied at had in common: none of them offered adequate environmental education.

“I didn’t really have an introduction to environmental education until, like, 11th grade,” Owoeye said. “I took AP Environmental Science and actually fell in love with it. I [thought] ‘I really like this program and curriculum,’ and [tried] to bring that kind of passion here.”

Owoeye wasn’t planning on studying environmentalism in college. It was international relations that initially fascinated her the most, but after engaging with environmental studies during her junior year of high school, Owoeye developed a deep fascination with the subject, choosing to bring it to university with her.

NYU was Owoeye’s first choice due to the opportunities available in New York, from living close to U.N. headquarters to going to a school with a strong international relations program. Since starting her journey at NYU in the fall of 2018 as an environmental studies and international relations double major in the College of Arts and Science, Owoeye has realized her experience wasn’t an isolated case.

“After getting to talk to other students [at NYU] I understood the lack of access to environmental education,” Owoeye explained. “I thought it was interesting, how earth science is not prioritized in comparison to biology or different [sciences] people are required to take within their secondary education.”

Feeling privileged to have had access to environmental education in high school, Owoeye wanted to bring the opportunity to communities deprived of such a chance.

“If you don’t introduce it early, it’s like robbing someone of an opportunity to get into environmentalism,” Owoeye explained. “A lot of people that I’ve tutored are literally in their thirties and they were never given the same opportunities to learn about it.”

Throughout her first year at NYU, Owoeye began tutoring for the Petey Greene Program as well as for younger kids whenever she went back home to Baltimore, and for other students through NYU’s Academic Resource Center. Through her teaching, she aimed to foster deeper understanding of the ways to teach environmentalism to different groups of people, taking into consideration their ages, lifestyles and socioeconomic statuses.

“There was a difference of how people will accept that kind of information [about the environment] if they had never had a prior experience with it. That’s why it’s interested me to expand on the environmental education.” Owoeye said. “The environmental movement is moving towards action [and] mobilization-based kind of movement but without the education of it, it’s very ostracizing to some people because they can’t access that.”

Some of Owoeye’s older students are the inmates at the detention facility in the Bronx that NYU PEP assigned her to teach at. Every Friday morning, Owoeye would travel there from Manhattan, a trek of around two and a half hours.

Having been interested in the U.S. justice system from a young age, Owoeye used to want to be a lawyer. Even though this has changed, her fascination with the system and desire to strive for a better one hasn’t.

“I grew up in communities affected by the police [brutality] but it hadn’t necessarily affected me within my immediate family,” Owoeye said. “I was also the type of kid going to social justice conferences and speaking about conceptual and abstract forms of oppression. But I felt like if I wasn’t exposed to the people I was advocating for, it wasn’t as powerful.”

The PEP curriculum being geared toward getting her students to pass their General Education Development test, an alternative for a high school diploma, Owoeye primarily taught GED sciences as well as test-taking skills and, occasionally, mathematics.

“I try to incorporate stewardship education while teaching the science section,” Owoeye said. “It’s not like there was an opportunity for me to just take a break from teaching the TASC [Test Assessing Secondary Completion] because they want to pass it. That’s what I’m there for and I’m not going to like push my own interest.”

She tried to incorporate environmental education through every loophole she could find in her established curriculum. Making the information accessible and applicable to real life were her priorities whenever it came to teaching environmental stewardship.

“I’d bring articles for them to read, for example,” she said. “For someone who’s older and in a detention center, I cater to their reality. If they’re from New York, I’ll talk about how much you notice trash on the floor. Like, isn’t it annoying when trash flies in your face?”

Her approach of teaching through familiarity and talking about what her students care for was influenced by her rejection of the most commonly used tool in environmental education: guilt.

“If you never give someone the opportunity to learn about something in the first place, the guilt is unacceptable,” Owoeye stated. “If I know and continue to do it, okay, shame on me. If I’m doing something and I don’t know the background to that, you can’t blame me.”

With Owoeye’s other students, her approach to explaining environmental stewardship doesn’t change much. When it comes to teaching younger students, Owoeye likes to start with the basics, talking about the three Rs: reduce, reuse, recycle. She said recycling tends to be talked about the most, when it’s in fact the weakest of the 3 Rs.

One of the examples she uses with her younger tutees to teach them about reusing and reducing the waste they produce revolves around a candy — their favorite one, of course — in a colorful wrapper. A kid wouldn’t care about the wrapper; instead, they think about the sweet inside of it. Owoeye suggests: what if the wrapper could be used to decorate something, to make something the child would care about?

“Shifting the focus from why we have single-use space to what you can do with [it] is important,” Owoeye laughed. “That’s when you [can] bring in craft activities.”

When it came to working with us, her peers, Owoeye’s goal was to bridge the gap in knowledge between us. To do this, she started a series of Instagram stories called “Cultivation of Consciousness” in July, posting about good and bad environmental news across the globe and sharing her take on the issues.

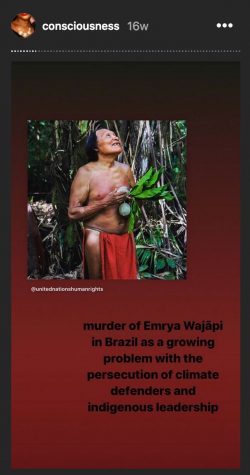

Her first set included stories with such captions as “2020 Olympics will be making medals out of the precious medals of recycled electronic devices” reported by CNET and “Murder of Emrya Wajapi in Brazil as a growing problem with the persecution of climate defenders and indigenous leadership” as covered by the United Nations Human Rights Office.

Examples of Eni’s Instagram series “Cultivation of Consciousness.”

“It’s split into ‘What I Praise For’ and ‘What I Pray For,’” Owoeye explained.

Not only does Owoeye educate her peers online, she does it in a classroom, too. This fall, she became a College Leader in the College of Arts and Science.

Standing by the projector in GCASL 269, I observed her first-year students flood the in. They were her CAS first-years, and she greeted and chatted warmly with every student while they signed the attendance sheet. As a College Leader and a sexual health educator myself, I took meticulous mental notes.

College Leaders collaborate with CAS academic advisors and teach biweekly, discussing everything that’s important to know about NYU and life in New York City. The class I attended revolved around study away opportunities for when Owoeye’s students finish their first year. Even so, Owoeye wasn’t going to miss an opportunity to talk about what’s relevant in the world of environmentalism with her students.

Once the students were seated, Owoeye started the lesson with what she referred to as “hot topics in environmentalism.”

According to Owoeye, she borrowed the “hot topics” idea of from Gabrielle Carmine, who taught Owoeye in a recitation for Nagle’s class. After graduating from NYU with a degree in Environmental Studies, Carmine went on to do her Ph.D. in Marine Science and Conservation at Duke University.

Throughout their time as teacher and student, Carmine and Owoeye developed a bond solidified by the former’s passion for teaching and the latter’s genuine interest in what was taught.

“As a teacher you expect the conversation to go in a certain direction,” Carmine laughed. “Eni’s hand was in the air all of the time and she took the conversation in a completely different direction with her insights.”

In her iteration of “hot topics,” Owoeye took five minutes to talk about the movie “Dark Waters,” which came out in the U.S. on Nov. 27. The move felt much like everything else Owoeye does in her teaching to get people interested in environmental stewardship. The movie has a whopping 93% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, and it was bound to engage her students with one of the key moments in modern environmentalism: the New York Times investigation by Nathaniel Rich into unexplained deaths linked to DuPont, an organization formerly known for producing polymers.

As I observed Owoeye interacting with her first-year mentees and listened to her describe her teaching strategies within communities, ranging from young children to the inmates in detention, I considered making a “How to Engage Your Students” guide based off of her approach. It would come in handy for my own teaching.

Here’s how the guide could begin: “Care about what you educate on enough to go a thousand extra miles.”

Email Anna-Dmitry Muratova

at [email protected].