Despite their occasional struggle to find an open mountain to climb in Manhattan, NYU’s rock climbing team has built a unique community of students who compete, hang out and form finger calluses year-round. Its goals are to foster connection, reckon with absurd climbing gym fees, defy climber stereotypes and embrace the outdoors — all while living in a city that stacks the odds up against them.

NYU climbing is barely two years old and the organization is already one of the biggest on campus. With 150 members on the club team, 12 members on the competitive team and almost 200 signups, there are an abundance of NYU students who have already come together to take on the plastic mountaintops at NYU climbing’s gym, Movement, in New York City.

“We’ve been able to introduce so many new people to climbing that never would have had the chance to if our club didn’t exist,” said CAS senior Adalea Khoo, president and founder of NYU climbing. She is also the head coach at VITAL, a popular bouldering gym in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

Khoo got her start climbing at a gym just a mile down the street from her childhood home in Seattle, Washington. She has been competing for over a decade, most recently qualifying for collegiate nationals last summer, representing NYU in Gilbert, Arizona. She placed 30th overall in the lead and top rope event.

It is safe to say that most NYU students do not possess over ten years of competitive climbing experience, nor do they have the privilege of spending upwards of $125 a month to join a gym here in the city. Khoo’s initial reason for forming NYU climbing two years ago turned out to be the team’s crux — to improve accessibility and exposure within the climbing world. This means utilizing the university’s resources to fund both its experienced and amateur climbers, as students of all levels and backgrounds are permitted to join the club and sign up for events.

“I would ask my friends to come climbing, but it costs $40 to get into the gym,” Khoo said. “I only climb in a gym because I have a free membership from coaching, but there are so many people that cannot afford it, and that is why we needed a school club with resources and funding.”

In addition to the substantial financial obligation, there are also impeding stereotypes and conventions regarding what it means to be a proper climber. Since the sport’s surge in the U.S. during the mid-20th century, climbing has been a predominantly white, upper-class space due to the historically exclusionary practices in national parks and outdoor recreation.

Khoo admitted that the gym’s demographic can feel like an overwhelming number of “young professionals that just came into a lot of money and don’t know how to spend it.” But this stereotype — despite its occasional accuracy — can be misleading in regards to the sport’s eccentric and diverse community.

“There is a place for everyone — we do have a lot of computer science majors, but I’m environmental studies, our event coordinator’s collaborative arts from Tisch and our communications officer is an MCC major in Steinhardt,” Khoo said. “I want to show that, if you search for it, there’s every type of person in climbing.”

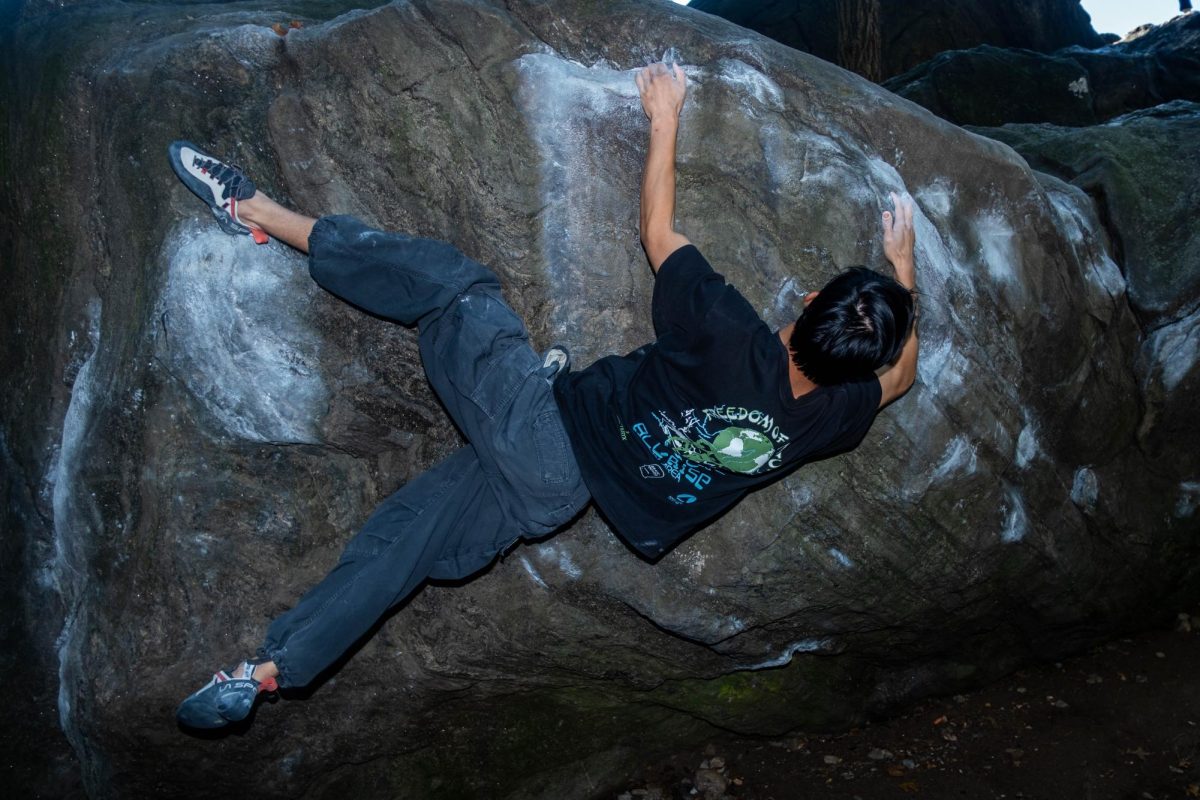

With that, the team’s directive remains clear. No matter who you are, climbing is and has always been about simply “going outside to touch some real rock.”

Climbing is a lifestyle, after all, and wherever you decide to climb — outside in Central Park, the bouldering wall at Palladium Athletic Facility or Movement — you are bound to experience the sport’s distinctive, down-to-earth quality that has drawn so many NYU students to the club. Even if you live in an urban environment, finding a rare rock that you can climb and the right people to do it with is like finding a hidden treasure — in both the city and in yourself.

Contact Levi Langley at [email protected].