NYU is facing 10 class action lawsuits alleging that it mishandled applicants’ personal information and failed to meet national cybersecurity standards after a hacker leaked files with more than 3 million names, hometowns and GPAs on the university’s website last week.

The lawsuits, each filed by an individual applicant, claim that NYU’s cybersecurity practices do not follow guidelines set by the National Institute of Standards and Technology and the Center for Internet Security, leaving those who applied to the school at risk of identity theft. Cybersecurity experts Zack Ganot and Arnaud de Saint Méloir, who help run databreach.com, told WSN that the amount of information included in the files — which were publicly downloadable on NYU’s main website for over two hours — could have sold for tens of thousands of dollars on the dark web.

“Almost for sure, NYU will settle and people will receive compensation — it was a real breach,” Ganot told WSN. “Without putting it too bluntly, it was NYU’s fault. They did not secure the data as they should have, and it’s kind of hard to get around.”

A university spokesperson did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

In a universitywide email sent about six hours after the breach, senior administrators Martin Dorph and Don Welch said that NYU removed the hacked page and reported the incident to law enforcement. In a second email five days later, they said that NYU IT and its cybersecurity consultant were “working as swiftly as possible” to evaluate what personal information was susceptible to unauthorized access. Alumni and unenrolled applicants, whose data comprises around 98% of the leak, have not received communications regarding the incident.

The lawsuits criticized NYU for not issuing a “prompt and accurate” statement informing the millions of applicants that their personal information had been compromised. William Federman, a lawyer in one of the cases against the university, told WSN that an immediate text, email or press release explicitly notifying applicants that their data was leaked would have been an ideal response.

“Imagine being an alum of the [University Heights] campus and now learning that your personal data has been stolen and is potentially being misused,” Federman said in a statement. “You would have high anxiety and not even know where to start.”

In an interview with WSN, Alexander Grijalva, an SPS professor teaching project management and IT, said he believed that NYU “disclosed as much as it could” and that the response time was likely inhibited by legal advisors and administrators’ caution confirming the university’s specific concerns surrounding the breach. Grijalva said the university issued its statement “faster than some institutions would,” and that the forensic processes that offer more details would take months.

“I would never criticize the university, because being in this job, I know how tough it is — in institutions of any size,” Grijalva, who is also the chief information security officer at VillageCare, said. “There’s so much data floating around, so many thousands of users and you can’t lock down 100%. The only way to have 100% security is just to get rid of digital technology.”

Several of the lawsuits specifically criticize the university for retaining applicants’ data for decades, citing industry guidelines that recommend encrypting or disposing of information as soon as it is no longer relevant. NYU’s policies stipulate that application data is destroyed after a two-year period, with the exception of enrolled students, whose data is destroyed five years after they graduate.

While over 99% of the data represents applicants from 2009 and later, records date back to 1978 and can be found across all schools, and for both admitted and rejected applicants. Federman said that while some of the retained information may still be relevant for advertising or analytics, it should be stored on a separate hard drive to mitigate accessibility risks.

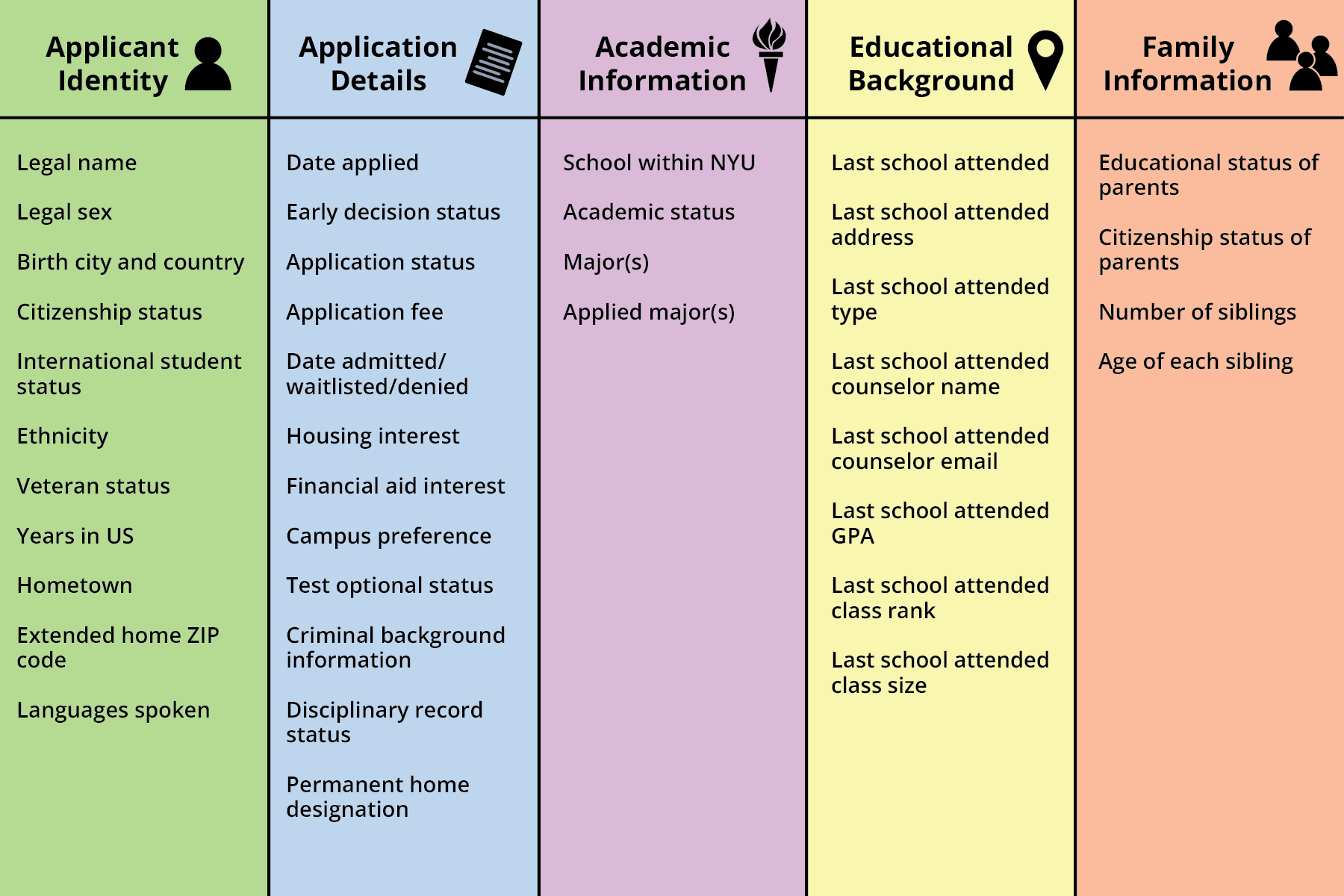

Compiled, the files include each individual’s SAT and ACT scores, zip codes and ethnicity, among other personal information submitted on the Common Application. De Saint Méloir said the breach was the first he has seen with GPAs. The lawsuits claim that while the files did not include phone numbers, home addresses or social security numbers, the available information is often enough for hackers to find them.

“The good news — but the bad news — is that I didn’t find any social security number, so I don’t think the compensation will be that large,” de Saint Méloir said. “But also it depends on the net profit of the company — considering NYU is one of the richest universities in the country, it could be an interesting settlement.”

Over the past several years, similar incidents have taken place at the University of Minnesota — which was seemingly hacked by the same person who took over NYU’s website — Marymount Manhattan College, Syracuse University and several other schools. In most cases, institutions faced an onslaught of class action lawsuits before they consolidated into one. Students who filed claims in lawsuits received $38, $150 and up to $1,000, respectively — although all breaches involved SSNs.

Along with links to download the data, NYU’s hacked page displayed three charts with what the hacker claimed to be the university’s average admitted SAT scores, ACT scores and GPAs for the 2024-25 admissions cycle. On the defaced website, the hacker argued that NYU uses “illegal” race-sensitive admissions, showing that the average admitted test scores and GPAs for Asian and white applicants were higher than those who identify as Hispanic or Black.

In their email to the NYU community, Dorph and Welch said that the graphs were both “inaccurate and misleading.” WSN verified the information of over 50 consenting NYU applicants but did not find any inaccuracies. In his look into the files, de Saint Méloir said the charts are consistent with the data but noted that less than one in 20 admitted students included their test scores in the last application cycle.

“These claims are statistically worthless,” de Saint Méloir said. “You need a much deeper study to validate that conclusion or not.”

Two days after the data breach, NYU’s Black Student Union released a statement criticizing the university’s response and WSN’s article published immediately after the hack. The group said the incident was particularly concerning amid a federal crackdown on diversity, equity and inclusion programs in the United States, and that its members plan to work with NYU leadership and the Student Government Assembly to more thoroughly address the issue.

“Nowhere does the university acknowledge that this attack disproportionately targeted Black students or address the underlying motivation of racism,” the BSU statement read. “This was not just a data breach; it was an act of blatant racism designed to perpetuate harmful narratives about Black and Latine students.”

Ganot said that the “hacktivist” had a clear political motivation and that it “speaks volumes” that the attacker didn’t ask NYU for ransom — which, “based on historical trends,” could have been around $1 million. In the same interview, de Saint Méloir said that in most instances, this amount of personal information would have only been available on the dark web, noting that this was the “easiest to access” data breach he had seen.

A breach of this level would have previously resulted in an investigation by governmental agencies such as the Federal Trade Commission or the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Ganot added. However, he said the Trump administration’s firing sprees have restricted the agencies’ capacity for oversight.

“They basically were shut down, and everyone knows they were shut down, so that’s not going to happen,” Ganot said. “The only way to hold a company accountable right now, is filing a class action lawsuit.”

Contact Dharma Niles and Krish Dev at [email protected].