A team of 14 researchers at NYU found that cancer cells cooperate with each other in order to survive challenging conditions, contrasting decades of previous research focused on their tendency to compete.

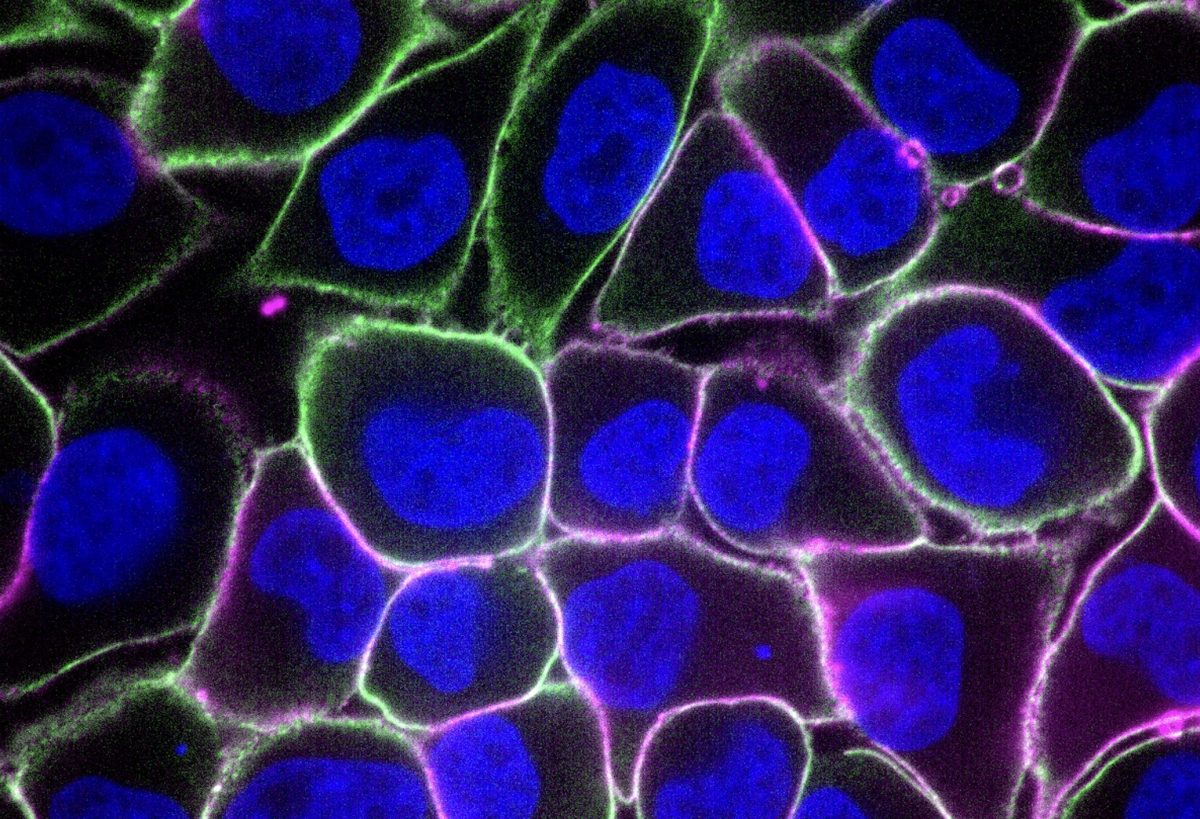

In the study published in Nature Medicine last month, researchers observed cancerous cells as they received varying levels of nutritional support. Tumor cells usually compete for amino acids — the building blocks for proteins — as a source of nutrients. However, researchers found that when there are fewer amino acids available, the cells begin to evenly distribute the nutrients instead.

“As of now there isn’t any study similar to this one, so this is novel research being published,” Gizem Guzelsoy, a lead researcher of the study who earned her Ph.D. in biology from NYU, said in an interview with WSN. “It’s amazing.”

When cancer cells have limited nutrients available, instead of directly absorbing them, they will secrete an enzyme that breaks them down into independent amino acids. The process creates a shared nutrient pool that cancer cells collectively use to stimulate growth.

Researchers hope that their findings will help scientists create cancer treatments that target cooperation among cells. The bestatin drug, designed to leverage cell cooperation, has demonstrated limited effectiveness on its own — but by further defining the cooperative process that takes place, scientists could refine the drug’s ability to prevent cancer growth.

Setiembre Elorza, another lead researcher of the study and Ph.D. candidate at NYU, told WSN that scientists have long known that as cancerous cells grow, they become more competitive with each other to fight over nutrients. Elorza said that the new research is shifting how scientists perceive tumor behavior. The most recent study found that the cancer cells’ behavior mirrors that of living organisms, who also cooperate under harsh conditions to survive. For example, penguins huddle together in periods of abnormally cold weather to preserve warmth, prioritizing larger groups in colder temperatures.

“The more we understand and the more ways we have to look at the problem, the more chances that we will find new solutions,” Carlos Carmona-Fontaine, another lead author and NYU associate professor of biology, told WSN.

Contact Amelia Hernandez Gioia at [email protected].