NYU’s closure of a public space in the Paulson Center likely violates the terms of an agreement with New York City, according to an urban planning expert. Some organizations at NYU, including Shut it Down NYU and the university’s chapter of Faculty for Justice in Palestine, have also raised concerns that the university may be intending to suppress protests with the policy.

Since the start of the spring 2024 semester, the university has required visitors to show an NYU ID card to enter the Paulson Center atrium along Bleecker Street, effectively closing the space to the public. After a March 27 demonstration, Shut it Down NYU and Jews Against Zionism made an Instagram post calling attention to confusion on the accessibility of the space.

“Although this lobby is a public space, NYU has been restricting access to only NYU ID holders, putting up borders between the New York City community and the private institution that constantly gobbles up land,” the post reads. “This is a clear escalation on the university’s part and is a brazen attempt at repression of our presence in a lobby we have a right to occupy.”

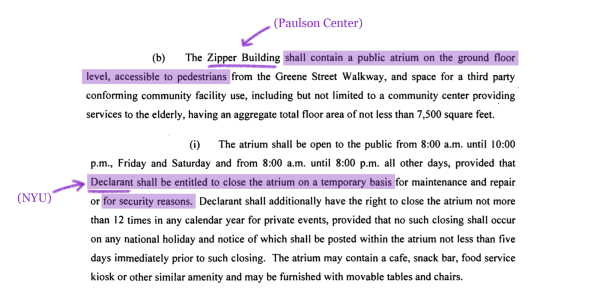

The dispute over the legitimacy of the restrictions stems from differing interpretations of a 2012 agreement between NYU and the city. The agreement, a type of city planning document called a Restrictive Declaration, sets the terms of NYU’s use of the land slated for its expansion plan, including the 181 Mercer St. site where the Paulson Center now stands.

The Paulson Center atrium exists today because of two paragraphs in the Restrictive Declaration where NYU agreed to build “a public atrium on the ground floor level, accessible to pedestrians.” The agreement also allows the university to “close the atrium on a temporary basis for maintenance and repair or for security reasons.”

NYU’s interpretation of those two paragraphs is laid out in a recent memorandum authored by two top university officials, executive vice president Martin Dorph and general counsel Aisha Oliver-Staley, which was obtained by WSN. They wrote the memo for Campus Safety officers to distribute to students at the Paulson Center who were challenging the university’s closure of the public space.

They open by claiming that the atrium is not a privately owned public space, or POPS — the first point of contention. A POPS is a public area inside or adjacent to a building constructed and maintained by a private entity like NYU. In negotiations with the city, developers agree to construct these spaces for public use in exchange for exemptions to zoning regulations. University spokesperson John Beckman reiterated the university’s assertion that the atrium is not a POPS in statements on behalf of Dorph and Oliver-Staley.

Jerold Kayden, an urban planner and lawyer at Harvard University, popularized the term with his 2000 book “Privately Owned Public Space: The New York City Experience.” He’s since led work to catalog and expand education on POPS.

In Kayden’s view, NYU is wrong about the atrium based on its description in the Restrictive Declaration document: “As I see it, it’s a POPS,” he told WSN.

Kayden told WSN that those two paragraphs in the Restrictive Declaration define a privately owned public space, even though they don’t use those exact words. It does not need to be named as such in order to be one, he said, because the phrase “privately owned public space” is not a formal legal term.

In order to build the Paulson Center, NYU committed in the Restrictive Declaration to build the atrium for public access — the building permits for the site required that NYU had to file the Restrictive Declaration in order to begin construction. That makes it a standard POPS, Kayden said.

NYU contends that the only POPS at Paulson is the Greene Street Walk — a pedestrian walkway on the west side of the building that connects Bleecker Street and West Houston Street. The Restrictive Declaration grants the public access to the Paulson atrium from the Greene Street Walk.

On the window of the public entrance to the Paulson Center atrium, text states the “plaza is open to the public” without specifying whether it’s referring to the outdoor area, the indoor atrium or both. The window text also states the atrium hours of access, declaring that the space may be closed for private events “at least” 12 times a year. Such closures are in fact allowed “not more than” 12 times a year, according to the Restrictive Declaration.

The second paragraph of Dorph and Oliver-Staley’s memo states that NYU has not closed the atrium but has “temporarily restricted entry to members of the NYU community with ID cards.” In the following paragraph, the administrators wrote that NYU would be permitted to fully close the atrium for security reasons and that “longstanding university rules” require students to show their IDs when asked by a Campus Safety officer before entering a building.

The memo reiterates that Campus Safety is allowed to let students and faculty into the building while turning away anyone who does not show an NYU ID. However, the student conduct policy says only that students must show ID when asked, but does not have any information specifically about entry to university buildings or public spaces. The Restrictive Declaration also has no provision explicitly allowing the university to do so. But Beckman said the agreement gives NYU permission to close the atrium “without enumerating every possible scenario” that might be allowed and that “reason and common sense” justify the ID-checking policy.

However, Kayden disagreed with the university’s restrictions of the space.

“If it’s temporarily closed for security reasons, it has to be closed to everybody,” Kayden said. “They can’t close it and just have it be there for students.”

Dorph and Oliver-Staley cite a rule in Exhibit H of the Restrictive Declaration that requires members of the public to comply with commands from Campus Safety officers. However, Exhibit H has nothing to do with the atrium, but rather outlines rules for a set of publicly accessible outdoor areas. Beckman confirmed in another response that the Paulson atrium is not one of those areas, but did not respond to a question about the misclassification of Exhibit H.

Aside from Exhibit H, the Restrictive Declaration nor the student conduct policy define Campus Safety’s authority over members of the public, leaving it unclear whether non-NYU community members coming to the space must follow Campus Safety commands or comply with requests to show their ID.

On March 30, demonstrators held a pro-Palestinian demonstration at Paulson where protesters allegedly “violently” attempted to open doors and “blind” security cameras, according to a statement Beckman wrote to WSN. He said that due to this, the university chose to restrict access to the space, reiterating previous allegations that a student had “summoned” protesters into the building. The student had previously told WSN that they were not telling protesters to enter the building, but were rather redirecting them to go around the building.

However, many students don’t think the choice to restrict the space is helpful in ensuring student safety.

“To shut down the lobby just in case — I don’t think it’s making it any safer,” Silver junior Bella Berg said. “It’s making it more annoying, and it’s making it harder to get to class.”

Berg said she had made multiple calls to 311 — the city hotline responsible for fielding complaints about public services and spaces — because she believed the atrium was a POPS that NYU was not allowed to close to the public.

At an April 8 teach-in at the Paulson atrium about the Palestinian cause, an NYU professor, who asked to remain anonymous due to employment concerns, told WSN the location had been chosen in December because it was open to the public.

The professor said that organizers intended to “use the public access space so that we can, as NYU is always saying, be in community with our neighbors — not be closed off from our neighbors.”

NYU Law student Ryna Workman was also at the April 8 event. They spoke to attendees about NYU’s restrictions on the public space, contending that the closure is meant to suppress protest.

“My concern is that instead of actually being about safety, it is about the repression of keeping this space open and talking about Palestine,” Workman told WSN. “Right now it seems like they’re picking and choosing which parts of the Declaration to apply in a way that allows them to continue to repress students.”

Workman was the subject of widespread controversy in October when, expressing support for Palestinian resistance, they wrote in a Student Bar Association newsletter that Israel created the conditions that led to Hamas’ attacks. Criticism from both outside and within the university preceded their removal as the association’s president.

Beckman’s statement noted that, despite the partial closure, teach-ins and other student actions had occurred in the space since the start of the semester. He said NYU has made these changes in order to maintain student safety amid heightened protest activity across university campuses.

“The reason that the university has done so is that we have observed that at many campuses where demonstrations got out of hand and became violent,” Beckman said. “One of the issues was the presence of non-members of the university community.”

The temporary restrictions have now lasted about three months with no guarantee on when they will be lifted. Kayden said this constitutes another violation of the terms of the space. While the Restrictive Declaration allows for closures on a temporary basis, “an indefinite closure to the public stretches the meaning of ‘temporary,’” Kayden said.

Beckman said the university would reevaluate the security situation at the end of the semester to determine if the restrictions would continue.

Contact Alex Tey at [email protected].