A new study conducted by NYU Grossman School of Medicine researchers indicated that mice are able to use a combination of scent and social interaction to avoid aggressors after an attack. The study, which was published on Jan. 24, found that a mouse begins to associate an aggressor’s scent with pain signals after it has been bitten, teaching it to avoid it in the future.

The study looked at the impact of rodents’ rapid social learning — a theory that social behavior is developed through the observation of others — after a fight.

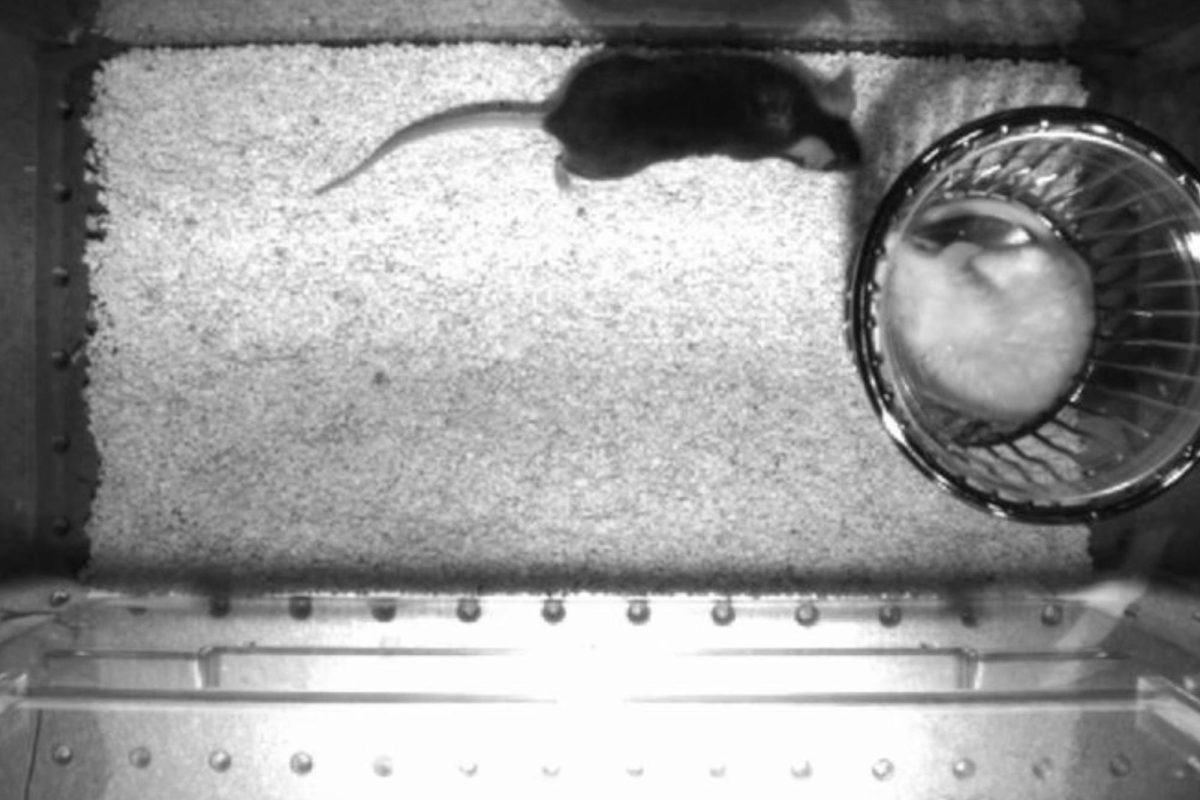

The researchers measured mice’s brain activity 1 minute before and 10 minutes after they were exposed to a different mouse, and found that the attacked mouse’s interactions with others dropped at least 20% 24 hours after losing a fight. The response mirrored human tendencies to self-isolate after experiencing similar instances of “social defeat” like bullying.

“This is a very common phenomenon, not only in mice, but also in humans and across a lot of different species,” Dayu Lin, an author in the study, said in an interview with WSN. “We’re trying to understand what might have happened in the brain that supported the species to change.”

After a fear-based encounter, the hormone oxytocin binds to cell receptors on the underside of the mice’s hypothalamus, the area of the brain responsible for maintaining stability within the body. This process makes it so that mice associate pain signals with an aggressor’s scent, sending a signal that is strong enough to warn them when a potential aggressor is approaching.

The researchers also found that when they prevented the cell receptors from binding to oxytocin, the mice were less likely to know how to avoid aggressors in future encounters. However, if they artificially activated the cells, the mice did not engage with their opponents.

Contact Zoe Alford at [email protected]