Documents reveal aftermath of Maitland Jones firing

Maitland Jones Jr., the fired NYU professor who made international headlines this week, submitted an extensive appeal letter objecting to the termination of his employment. It was immediately dismissed by university administrators.

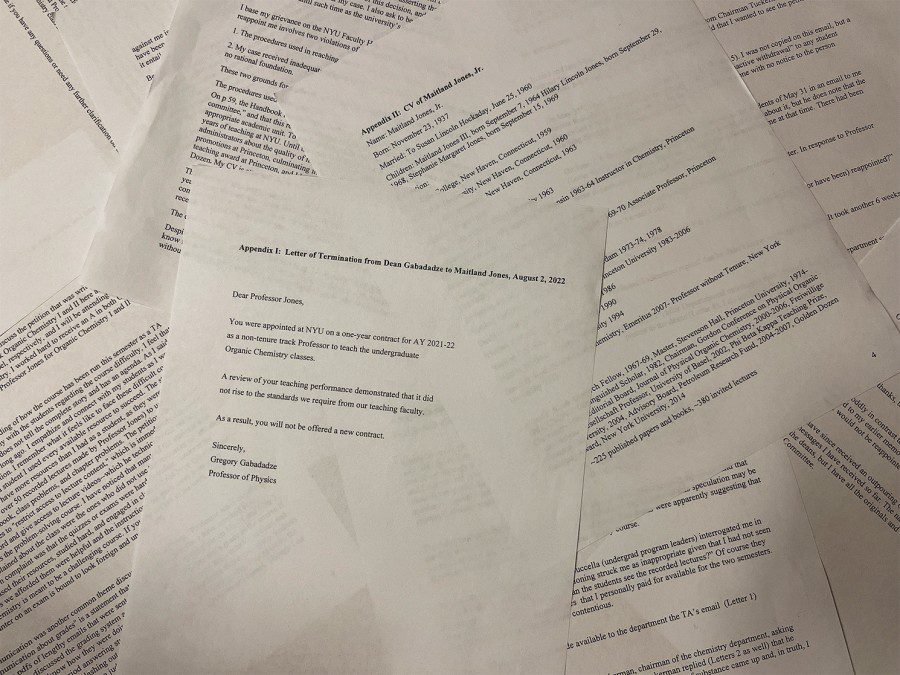

(Abby Wilson for WSN)

October 7, 2022

Fired NYU professor Maitland Jones Jr. attempted to formally protest the sudden termination of his contract with the university this summer, according to previously unpublished documents. But NYU administrators blocked his attempt to file an appeal.

The administrators tasked with passing Jones’ grievance letter on to a faculty-led grievance committee refused to allow the document to even reach the committee, instead determining that Jones was not allowed to appeal his dismissal. Heidi White, a faculty member with a senior role in the dispute review process said that the administrators’ decision was wrong, and that Jones’ grievance should have been allowed.

Most faculty members at NYU are entitled to file a grievance for a number of reasons — including if their contract is terminated. It is a formal explanation of a complaint they have about procedural processes at the university. WSN obtained a copy of Jones’ grievance letter, which had not previously been made public.

“As a method of making decisions goes, this is like hanging a man for murder while insisting at the same time that the decision to hang him is rational even without a trial,” Jones wrote in the letter. “If a student composes a petition and asks other students to sign it, is that now sufficient at NYU to end a professor’s career?”

In his 15 years teaching at NYU, Jones had only been employed on a series of one-year contracts, which had been renewed before the beginning of each academic year. Shortly before the start of the 2022-23 academic year last month, when his contract was up for renewal, he received a blunt email from Gregory Gabadadze, the dean for science, informing him that his contract would not be renewed.

Since Jones’ story made headlines — appearing on the front page of The New York Times on Tuesday — many have criticized the professor’s students for causing his dismissal. Last spring, a group of his students had signed a petition criticizing the professor for limiting access to online lectures, concealing grade averages, and talking down to students in his classes.

“In one of his organic chemistry classes in spring 2022 there were, among other troubling indicators, a very high rate of student withdrawals, a student petition signed by 82 students, course evaluations scores that were by far the worst — not only among members of the chemistry department but among all the university’s undergraduate science courses — and multiple student complaints about his dismissiveness, unresponsiveness, condescension, and opacity about grading,” John Beckman, an NYU spokesperson, wrote to WSN.

Faculty members have pushed back against criticism of his students, though, pointing to precarious employment terms that non-tenured faculty face at NYU.

This account of Jones’ battle with the university over the sudden loss of his job is based on interviews with several NYU administrators and faculty members, and a review of previously undisclosed documents detailing the conflict.

Jones declined to comment for this article.

Ineligible to Grieve

Each school at NYU has a grievance committee, which is composed of faculty members who are chosen by their peers. The committees investigate and address procedural complaints from faculty, including, but not limited to, those concerning promotion, tenure and reappointment decisions. The committees then bring recommendations to their respective deans, but cannot mandate that anything will be done about the grievance.

If a faculty member wishes to file a grievance, the offense must “involve violation of university-protected rights of faculty members.” The grievance must also assert that either the administration used improper procedures to make their decision, or that the decision “violated the academic freedom” of a faculty member.

Jones was classified under a category called “other faculty” — faculty who are not tenured or full-time contract faculty — meaning that he would not be eligible to file a grievance, according to an NYU spokesperson, John Beckman. Contract faculty members, who by definition are not tenured or on a tenure track, are eligible to file a grievance with the committee if a review of their employment concludes in recommending the termination of their contract.

Beckman did not respond to repeated questions about what parts of Jones’ contract led him to be classified as “other faculty” and not contract faculty, making him ineligible for a grievance claim.

Chemistry department chair Mark Tuckerman said that he was unsure of what made Jones’ contract different from those of other contract faculty members, and said that Jones had negotiated his own contract with the university when he began in 2007.

White — the faculty member with a senior role in the dispute review process — said that NYU administrators did not provide justification in classifying Jones as “other faculty.” She said that the reasoning remains unclear. White is also a member of the University Senate, serving as a senator on the Continuing-Contract Faculty Senators Council and as chair of that council’s Grievance Committee and its Personnel Policies & Contract Issues Committee.

“I confess, I’m baffled as to how the administration could have reached that conclusion,” White said. “To me, it looks like a blunder.”

The Lead-Up to Jones’ Termination

In Jones’ grievance letter, he encloses the notice of his termination from Gabadadze, his curriculum vitae, a timeline of correspondence and events, and letters of support from former students.

“I wish to file a grievance of this decision, and I ask that you convene our school grievance committee to hear my case,” Jones wrote in the letter. “I also ask to be fully reinstated as an NYU faculty member in good standing — until such time as the university’s published policies have been properly carried out.”

The correspondence cited in the grievance letter began on June 11, when Jones sent an email to Tuckerman, the chemistry department chair, asking if he would be reappointed for the following academic year. According to Jones, Tuckerman responded, but did not give a definitive answer. On June 28, an email from Tuckerman told Jones that he hoped he would have an answer in one week. Jones replied the same day.

“As of now I (think) I have not been reappointed,” the June 28 email from Jones reads. “Is that so? Will I be?”

Jones did not receive a response until three weeks later. He then found out, through Tuckerman, that he would not be reappointed by the university. On July 31, Tuckerman followed up with Jones, suggesting that there may be a way for the professor to return to the university.

“I read your email to the deans, and I just wanted to let you know that I share your sense of frustration with the situation,” Tuckerman wrote. “I have met with Greg Gabadadze in the last few days, and what I’ve understood from the conversation is that the Deans’ decision has been framed such that there is an option for the department to offer you a teaching position this semester, if continuing to teach would still be of interest to you.”

Tuckerman said the deans initially did not want to rehire Jones, who they expected would want to retire soon anyway.

“I think they decided, ‘He’s going to retire anyway, is there any real reason for us to renew the contract?’” Tuckerman said. “My recommendation was he should be re-hired for one more year. They felt differently. We disagreed on that.”

He also said that he advocated for Jones to return for one more year in a reduced role because he felt it would be difficult to hire a new professor on short notice. The deans were open to the idea.

Jones, however, was not satisfied with the way that the administration had handled the situation, and did not wish to continue the conversation. The deans, having heard that Jones did not want to speak, decided to stop considering the alternate teaching position, and instead made a final decision to terminate his contract.

“At the end of the day, they seem to find sufficient reason in the complaints they heard from the students and from the evaluations he had,” Tuckerman said.

Days later, on Aug. 2, Gabadadze sent Jones a letter of termination. The letter of termination, which is printed in full, explains to Jones that his one-year contract to teach organic chemistry would not be renewed.

“You were appointed at NYU on a one-year contract for [the academic year] 2021-22 as a non-tenure track professor to teach the undergraduate organic chemistry classes,” the termination reads. “A review of your teaching performance demonstrated that it did not rise to the standards we require from our teaching faculty. As a result, you will not be offered a new contract.”

Jones Protests Sudden Firing

In his grievance letter, Jones referenced NYU’s Faculty Handbook, which outlines that if a full-time professor’s contract finishes on Aug. 31, they must be notified of their termination no later than one year prior. Jones was informed that his contract would not be renewed on Aug. 2 — less than one month before it was set to expire. However, his designation as “other faculty” meant that these deadlines would not apply, according to Tuckerman.

In addition to Jones’ complaints about how the university handled his dismissal, he also claimed that he was never shown the student petition made to protest his teaching methods.

“Despite the assertion made about my teaching, I have never been given the slightest opportunity to know the actual substance, if any, of any complaints about my performance, and I would stress that without giving me that opportunity, the university has no way of knowing whether anything said against me is really true,” Jones wrote. “Whatever evidence might exist for a decision to deny me reappointment, I have been given no chance to see it, refute it, or challenge whether it really entails what one thinks it entails.”

Jones included a May 13 email that he wrote to deans Gabadadze and Merlo about a New York Times opinion essay titled “My Students Are Not OK.” In the email, he wrote that he believed the essay — which argues that pandemic-related loosening of student expectations is contributing to student apathy — describes the situation in his organic chemistry classes “perfectly.”

“There seems to be a strong consensus among teachers that we continue to ask less and less of our students,” Jones writes. “In chemistry 226, we, too, have 30% attendance in the lecture, silent students, empty office hours and plummeting grades on ever-easier exams.”

He went on to write that over the last decade, he had seen “something odd” — students misreading exam questions, even when he utilized boldface and colors to make them more clear. He also pointed to 50 recorded videos that he had created with fellow professors Paramjit Aurora and Keith Woerpel. Jones then listed four guesses he has to explain the “immense tuning out” of students that he said he has witnessed.

“This cohort of students is the victim of three years of Covid ‘learning,’” Jones wrote. “They not only don’t know how to study, many do not seem to even know that they should study.”

Jones concluded the email by reiterating his frustration that the student petition was never shared with him and asking that in the future, the university use a procedure that will better respect the faculty members involved.

Jones also included another email from May 31 from Tuckerman and director of undergraduate studies Marc Walters, which informed his students about grade adjustments and a retroactive withdrawal date for his course. Jones claimed that he was not sent this email, and was not informed of the policies that were included.

On July 11, Walters sent a follow-up email to Jones, explaining that the email was sent to students because deans were concerned about “the specter of a massive withdrawal” from Organic Chemistry II. He wrote that he hoped the email to students would ease tension.

“In hindsight, the deans should have contacted you directly with their concerns, and we should have discussed a reasonable resolution of this matter with you before any actions, or emails were launched,” Walters wrote.

The final section of Jones’ grievance letter included 22 emails from students — all of which expressed remorse that the professor had been terminated. Many directly addressed the petition; some students were unaware that it had been created, and others said that they were strongly opposed to its criticisms of him and the class.

“Shame on us for counting on an educational institution to prioritize education,” one student wrote. “I hope we lose you to Columbia.”

Contact Abby Wilson at [email protected].

Were you a student in one of Maitland Jones’ classes? Are you an NYU employee who can speak to the controversy surrounding the termination of his contract? WSN would like to hear from you!