Although young girls are arrested at a lower rate than to their male counterparts, they not only make up a growing proportion of teen arrests in the United States but are also disproportionately incarcerated for low-level offenses. To combat this, the program ROSES — Resilience, Opportunity, Safety, Education and Strength — at NYU’s Institute of Human Development and Social Change works one-on-one with young girls involved in or at risk of having involvement in the juvenile justice system and helping them effectively navigate personal challenges.

ROSES began as an experimental intervention when Shabnam Javdani, an associate professor of applied psychology and founder of ROSES, was first exploring the possibilities of community-based advocacy work at the University of Illinois. Through research, she discovered that there was a deep need for on-the-ground initiatives that divert kids from incarceration and deeper involvement in the juvenile justice system.

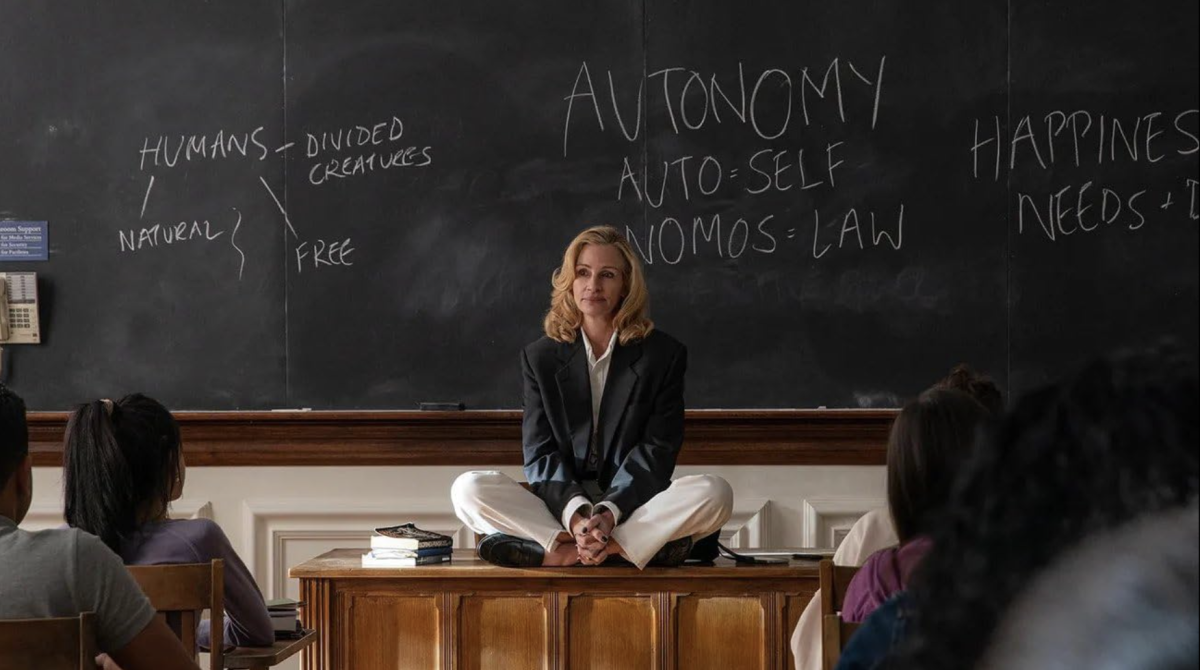

In 2012, Javdani established ROSES at NYU to disrupt the school-to-prison pipeline, a term used to describe the relationship between in-school punishment and adulthood incarceration. A 2021 study published in the Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice journal found that suspension between grades 7-12 led to a significant increase in the likelihood of incarceration in adulthood.

This is in part due to the zero tolerance policies many schools employ, which attempt to reduce misbehavior by suspending and expelling students for infractions. Many of the punitive measures are based on vague rules that disproportionately affect youth from marginalized communities, especially young Black girls, who, due to racial bias, are viewed as being “less innocent” than their white peers, leading to a suspension rate 1.6 times higher than their white counterparts. Facing such punishments at a young age can lead to lower test scores, more absences, lower graduation rates and ultimately puts them at a higher risk of incarceration.

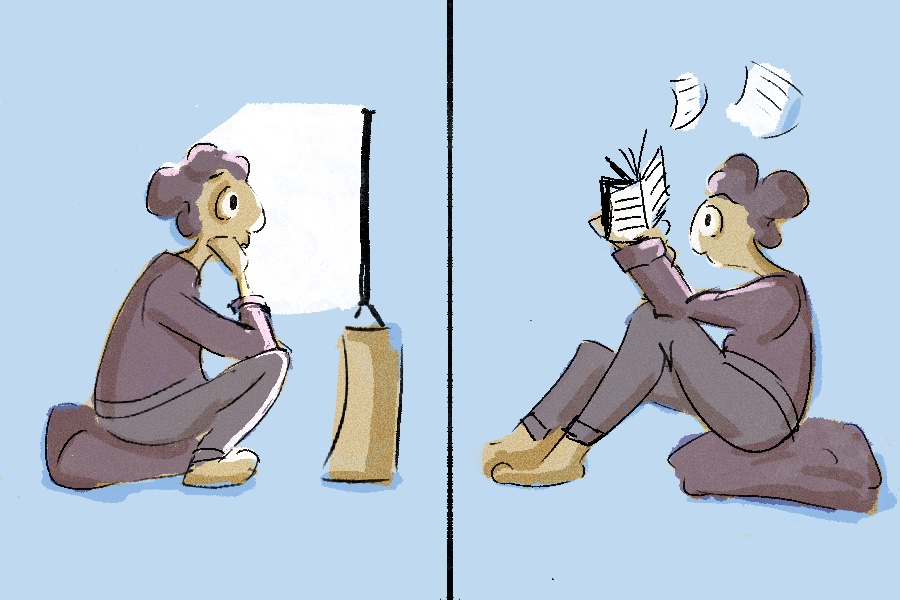

ROSES relies on the dedication of NYU students who serve as advocates for the young people they work with and teach them how to manage their lives independently, according to Genevieve Sims, who was a ROSES advocate in 2016 and now serves as the program’s supervisor and director.

“We talk a lot about putting ourselves out of a job by the end,” Sims said. “What we’re doing is [enhancing] somebody’s existing strength and supporting them through a stressful time and navigating the system. We’re not supplementing any abilities they don’t already have.”

Tisch junior Sam Del Rio, who started working as an advocate with ROSES as a sophomore, described an instance in which her client was facing expulsion from school. During meetings with school administration, she encouraged her client to come prepared with any documents and information that could prove she wasn’t at fault. After two meetings, she saw her client take control over her situation and utilize skills of preparedness, strength and self-advocacy.

“[One of my clients] didn’t want to talk about school or anything that had been going on [but later], being able to see her advocate for herself and stand her ground against what was happening to her, it was just so amazing to see,” Del Rio said. “I was just so proud of her. I think about her every day.”

The program requires a minimum of two semesters or 10 hours a week of training on the ROSES model, followed by engaging in the one-on-one partnership with a young person, who is generally referred to ROSES by the New York City Administration for Children’s Services, the New York City Law Department’s juvenile justice division, and local hospitals and social workers.

In addition to the young people they work with, Sims said ROSES has also impacted the advocates involved. For Sims specifically, her experience has provided new perspectives and a space to connect with people in the NYU community with similar morals and goals for social change.

“I think it was very necessary for me to be engaged in social justice, but also in a community space of women, femme, non-binary and trans people who were all on the same page, coming to the table with a shared value system,” Sims said.

Similar to Sims’ appreciation of the supportive community that defines the program, Del Rio sees the people and relationships she has at ROSES as “a breath of fresh air.”

“[ROSES supervisors] not only took care of me, but they also helped me find resources for my clients,” Del Rio said. “It’s a very supportive environment, and such a beautiful community of women.”

Being a community-based program that is rooted in fostering self-determination rather than simply punitive or rehabilitative practices — it has taken time and effort for state governments and officials to recognize the value of the work ROSES does.

“Judges across New York City are recognizing ROSES as an alternative to incarceration or an alternative to placement [in juvenile centers], and are using it as such,” Javdani said.

The program’s research and hands-on advocacy have proven that punitive and rehabilitative practices aren’t sufficient in fixing the disproportionate incarceration of young girls in the juvenile justice system based on race, socioeconomic status, gender identity and sexual orientation.

“Our motto is ‘change the context, not the girl,’” said Javdani. “It turns out that people thrive in a supportive context where people are asking about their needs and advocating for ways to meet those needs.”

The future of ROSES lies in the research being conducted by Javdani and her colleague Erin Godfrey, who directs the Institute of Human Development and Social Change. Currently, they are assessing the experiences of young people and staff in approximately 40 juvenile detention facilities across New York City, and the study’s results may reveal more ways to further the reach of ROSES.

“My hope with ROSES, ultimately, is to see [our efforts] happen on a larger scale, where we’re no longer incarcerating children,” Sims said.

Contact Paige Ablon at [email protected].