How I moved past my first-gen imposter syndrome

My parents’ expectations caused me to use perfectionism as a survival tactic. Proud to Be First’s Secrets to Success Panel showed me that I’m not alone.

Perfectionism can be a harmful way to chase success. (Illustration by Aaliya Luthra)

November 9, 2022

If I had to choose one word to describe the academic environment I grew up in, it would be “expectations.” I had to be successful in my future: have a promising career, a lovely house and a comfortable income.

After immigrating to the United States, my parents believed that a good education would yield a comfortable life with many freedoms. My father worked many odd jobs, and could not speak up against racist bosses and microaggressions out of fear that he would lose his job and income. While my mother was a brilliant student and hard worker, a successful career in America required more than a Pakistani college degree.

Growing up as a first-generation immigrant was difficult. My parents didn’t have the best earnings and we constantly moved from house to house. My parents did not want me to face the same struggles that they did, so my mother would always tell me that I had to have the highest grades in class and be the best student. This idea trickled down to me and my siblings.

I remember how much paper and ink my mother wasted on reading comprehension and math packets. Now, I won’t lie and say it didn’t work. Here I am, studying the subject I love at my dream school.

But constantly living up to my parent’s expectations has been and is still mentally taxing. A large part of me feels that failing would make my parents’ efforts amount to nothing.

I want to prove to my parents that leaving their country was worth it; I don’t want their efforts to be in vain. But this idea of being the best, for the sake of my success, contributes to my experiences of imposter syndrome — it hinders me from moving past my idea of perfection. When something didn’t fit my definition of perfection, my thoughts would spiral and convince me that if this one project wasn’t perfect, I would lose everything I’d worked so hard for.

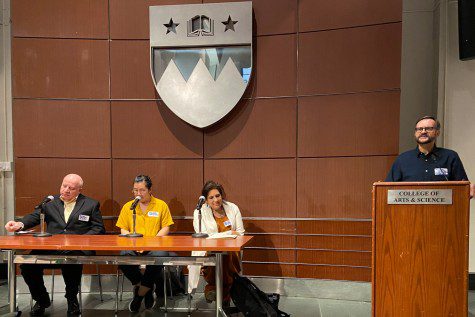

I am not alone in feeling like this. Hosted by NYU’s Proud to Be First, the Secrets to Success Faculty Panel on Nov. 7 featured three CAS faculty members who shared their educational journeys as first-generation college students and tips they learned over the years. While the panelists also dealt with imposter syndrome, they shared how they have fought against that feeling.

Fan Ny Shum, a mathematics professor and first-generation Chinese American, had trouble navigating college alone. As a math major who had not previously taken calculus, Shum found that there was a gap between her and her peers. However, she loved the challenge of taking her math courses and went on to get her Ph.D.

“It did take me time to try to get confident in myself to believe myself that yeah, I put in the work,” Shum said. “I’ve earned this degree, I’ve earned my title, I deserve to be here.”

It’s hard to let go of your idea of perfection when, for your whole life, it has been connected to success. The other day, after feeling that my essay wasn’t reading well, I convinced myself that NYU only accepted me on a whim and that I got lucky with my application essay. This sense of imposter syndrome and my toxic comparisons to others made everything I worked for seem insignificant. It’s hard to feel good enough to attend a school like NYU. My public school background felt astronomically out of place next to the many extraordinary characters here.

Chemistry professor John Halpin reflected on how he still feels imposter syndrome even to this day. Halpin said that he came from a long line of slackers where nobody in his family thought twice about college. It wasn’t until after years in the army, a motorcycle accident and remedial courses at a community college that he transferred to NYU for his senior year and graduate school. Throughout this experience, Halpin relates how he didn’t know the difference between “undergraduate” and “graduate.”

“I feel [imposter syndrome] every day — you don’t go around talking about it because no one wants to hear you talk about it in an everyday sense, but certainly it’s there,” Halpin said. “And I think that you do belong. And then if you have succeeded in your classes, if you have succeeded in sticking to the program — you know, because it takes a lot of self-discipline and self-motivation to do that — [and] if you manage to get as far as you are, then you do belong. It isn’t like there’s a secret membership or anything like that, but you may have asked yourself that for the rest of your life. I certainly do.”

Deirdre Royster, an associate professor of sociology at NYU, said that while her parents briefly attended Historically Black Colleges and Universities, they didn’t know very much about the post-secondary education system that they hoped she and her brother would attend. She says that feeling like you’re a fraud stays for a long time and that those personal doubts and insecurities do not just disappear.

“I think there’s another route to go that I call a survivor’s guilt,” Royster said. “For some folks who go on to college, you’re leaving friends behind who didn’t get a chance to go. As an African American kid in the D.C. area, I knew a lot of my friends were really smart, but they weren’t being tracked to take advanced placement classes and the SATs … I left behind a bunch of people who I knew were very bright.”

I don’t know if there will ever be a day when I can be fully confident in my achievements, but hearing about these panelists’ experiences with imposter syndrome reminded me and others that we are not alone. As these respected professors explained how even to this day they feel like they don’t belong, it lessened the burden on my heart.

Insecurities and doubts are human and there is not supposed to be a cure for them. You live with them, accept them and grow from them.

For me, making mistakes is something I have never been comfortable with. The fear of failure has forever burdened first-generation college students like myself, and to appease our parents, we’ve adopted an idealized sense of perfectionism. To break out of this cycle, one must remember that there is always room to improve — but, to improve, you have to make mistakes.

Contact Noor Maahin at [email protected]