A day of magical thinking at the Joan Didion estate sale

The Nov. 16 auction of Joan Didion’s belongings marked a final, posthumous turning point in the legacy of the perennial idol of aspiring writers.

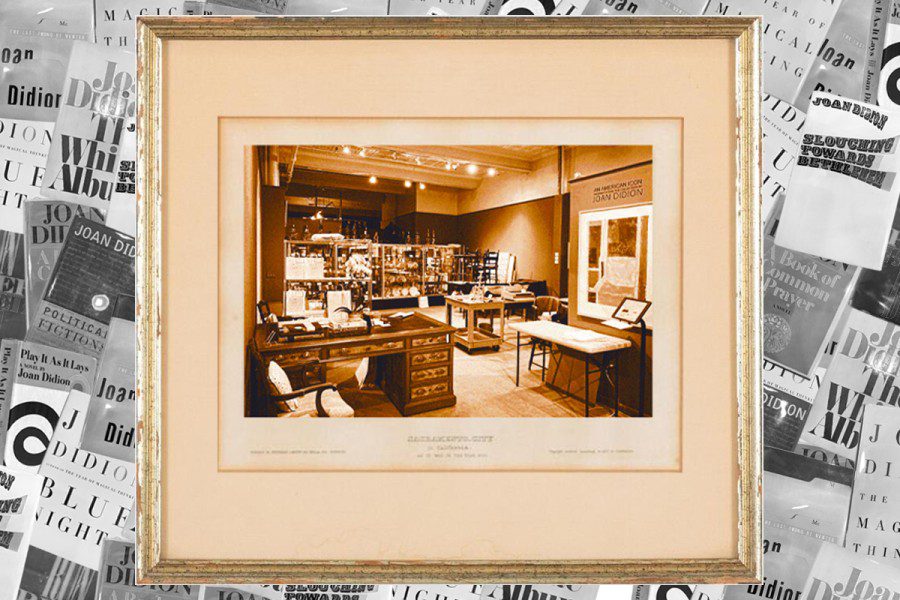

A selection of Joan Didion’s belongings were auctioned off by Stair Galleries in Hudson, New York. (Alex Tey for WSN)

November 21, 2022

I’m certain that, given the opportunity, Joan Didion would have attended her own estate sale.

The writer was the definitive chronicler of disorder and decline in 20th-century America. Later in her career, she delved into grief with reflections on the deaths of her husband and daughter. Through it all, in her reportage, fiction and screenwriting alike, she built a career on a knack for observation.

So when I’ve been telling people about my intentions to write about her estate sale, I tell them that I think it is what she would have done. An estate sale, at least to me, is one of the few events that feels more final than death. There is the dying, the funeral, the memorial service — last comes the estate sale.

Didion died in December 2021 at her Upper East Side apartment due to complications of Parkinson’s disease. A private funeral was held in April of this year, and a public memorial service took place in September. With the remembrances complete, the person of Joan Didion is now reduced down to her bare aesthetics and projected onto her artifacts.

“Many lessons had been divined, in both the death and the life,” Didion wrote of the author James Jones in one of the essays in 1979’s “The White Album.” Having not been a part of her life, I feel compelled to divine some lessons in her death.

The auction was conducted on Nov. 16 by Stair Galleries in Hudson, New York. The proceeds will benefit Parkinson’s disease research at Columbia University and a Sacramento City College scholarship for women in literature.

When I arrived in Hudson at 9:30 a.m. on Wednesday, I already knew I would not be getting what I had hoped for. I had found out a few days earlier — though not before buying my train tickets — that the sale would be conducted entirely on the online auction platform Bidsquare. No one would be allowed inside.

• • •

I show up to Stair Galleries anyway. I stand on the sidewalk for a while. I cross the street. I sit on the steps of the Hudson Whaler hotel, watching a woman walk up to the front door of the gallery, find it locked, look around a bit and turn to walk back the way she came.

I watch through the second-story windows as people move things around until Jo Olsen, the gallery’s creative director, steps outside wearing a long white coat around 10:40 a.m. I take the chance to introduce myself. She asks me if I am a reporter. The cold works to my advantage, and I am invited inside.

In the entryway, Olsen introduces me to Lisa Thomas, the director of the gallery’s fine arts department. They gently rebuff my attempts to watch the auction from inside the gallery, but do offer me a brief view of the room where the items are on display. I take in as much of it as I can: her writing desk, her dinnerware, her drop-leaf kitchen table where her husband died. Auras emanate.

About 10 minutes before one of Stair Galleries’ biggest auctions ever, Olsen and I walk down the block to get a coffee. She introduces me to the barista as a good friend of hers. They chat, comparing the impending auction to “Mad Max” — it’ll be “a thunderdome,” they agree.

A recent surge in Didion’s popularity among Gen Z — driven largely by TikTok, Olsen tells me — intensified the already iconic author’s status as an idol for young people aspiring toward sophistication. She points to “young, smart millennial women” who started book clubs during the pandemic as a key part of the trend.

Those who knew her, however, know that she would not have been a fan of her fans. “It’s always seemed to me that to turn Joan Didion into an emblem is to misrepresent a woman so averse to reflexive adulation or sentimentality,” writer Jia Tolentino said at the memorial service.

This is sort of the opposite of the point of a celebrity estate sale, of course. Many of the items on the block went on to fetch prices tenfold their estimated value because, well, it’s Joan Didion. She made you feel like you knew her.

“People feel that they can be close to an icon by owning something that that person lived with,” Thomas told the New York Times last month.

• • •

Olsen heads back to the gallery; I watch the livestream from my table at the coffeeshop. The auction commences with Lot 1, a collection of 21 copies of Didion’s own books from her personal library. It is estimated to sell for between $1,000 and $5,000. I watch the bids climb higher and higher. The winning bid is $15,000.

By Lot 5 — her iconic sunglasses — I have a sense of the kind of money that is being thrown around here. They are estimated at $400 to $800. Having just seen $163,000 spent in half an hour, as well as knowing that similar shades went for $2,500 in 2014 as part of a fundraiser for her nephew’s documentary, I expect the estimate to be low by an order of magnitude.

The sunglasses are non-prescription, the auctioneer advertises, so “you can wear them practically anywhere.” I try to imagine someone who buys Joan Didion’s trademark Celine sunglasses to wear them “practically anywhere.”

I do a lot of imagining, actually (magical thinking, if you will). The only thing I know about any of these bidders, each represented by a four-digit number, is that they have thousands upon thousands of dollars to spend.

Left to my imagination, I assume that every one is an impassive collector with impossible wealth at their disposal, interested only in prestige, exclusivity and status. That is easy to imagine because the online forum makes it hard to imagine anything else — it is absent of human passion of any kind.

“You’ll have so much regret if you don’t bid,” the auctioneer reminds the invisible audience as I watch bidders 3441 and 4319 battle over the sunglasses.

At $20,000, bidder 4319 drops out after a few thousand-dollar back-and-forths with 3441. Bidder 4514 takes their place, stepping in at $22,000. But 3441 wants it more. After 3441 counters 4514’s $26,000 with a final $27,000 bid, 4514 stands down.

I try to imagine someone who wants Didion’s sunglasses badly enough to spend $20,000, but not badly enough to spend $22,000. Someone else who has $26,000 to spare, but draws the line at $28,000.

At some point, the thrill is replaced with a bleak fascination. I couldn’t stop imagining what it would be like to own an object owned by Didion, couldn’t stop resenting the people who will get to, but after several hours of bidding, the tedium sets in.

I relocate to the town library. I am cold, tired, hungry; I forget what money means. Just $3,500 for a set of plates? A paltry sum, I thought to myself. Never mind the fact that my own set had cost a hundredth of that amount at IKEA — I was immersed in a different world.

At $110,000, a painted portrait of Didion — Lot 4, estimated at $3,000-5,000 — ends up being the most expensive sale. A group of art catalogues and a Victorian side chair — lots 104 and 126, estimated at $100-150 and $300-500, respectively — are the cheapest, each fetching a mere $1,100. A press release puts the total proceeds at $1.9 million.

• • •

So many young writers see themselves as Didion’s intellectual heirs. As pretentious as it sounds, I think I would be lying if I said that I don’t aspire to that myself. I also think that if you are the type of person to have read this far, you would be lying to yourself too if you said you don’t feel the same way.

Of course, not all of us get to be the next Didion. No one will be the next Didion, really, but the point is that many of us will try. David Remnick, the editor of the New Yorker, noted at the memorial service how she is especially admired by younger writers.

“I wish them all good luck,” Remnick said, addressing her many imitators. “She is inimitable.”

I don’t think that’s quite right, though. She is easily imitable, at least as I see it, precisely because of what makes her impossible to replicate. Didion’s aesthetics, both literary and personal, are so distinctive that it’s tempting to accessorize yourself in her style with designer eyewear or obscure adjectives. You can try on a declensionist paradigm like it’s a pair of oversized tortoiseshell sunglasses; you can assume a self-aware neuroticism like you’re picking up smoking.

This was what I found alluring about the estate sale, regardless of the fact that I could not really participate in it myself. The idea that one could secure a share of Joan Didion’s personality (at least, what one imagines her personality to have been) — it intoxicates.

With her belongings now claimed, her literary legacy is up for grabs next. It’ll take some time to sort the inheritors from the imitators. Until then, we are the grandchildren shortly after the death of the family matriarch, waiting to see who she thought to include in the will, waiting to see who will get the antique silver candlesticks and who will be forgotten.

None of us got the actual candlesticks, of course; they went to Bidsquare user 3204 — Lot 224, sold for $8,000.

Contact Alex Tey at [email protected].