What food said that words couldn’t

As a child of an immigrant mother, connecting with my grandparents and foreign family members can be challenging at times. Here’s the story of how food bridged those gaps when I personally couldn’t.

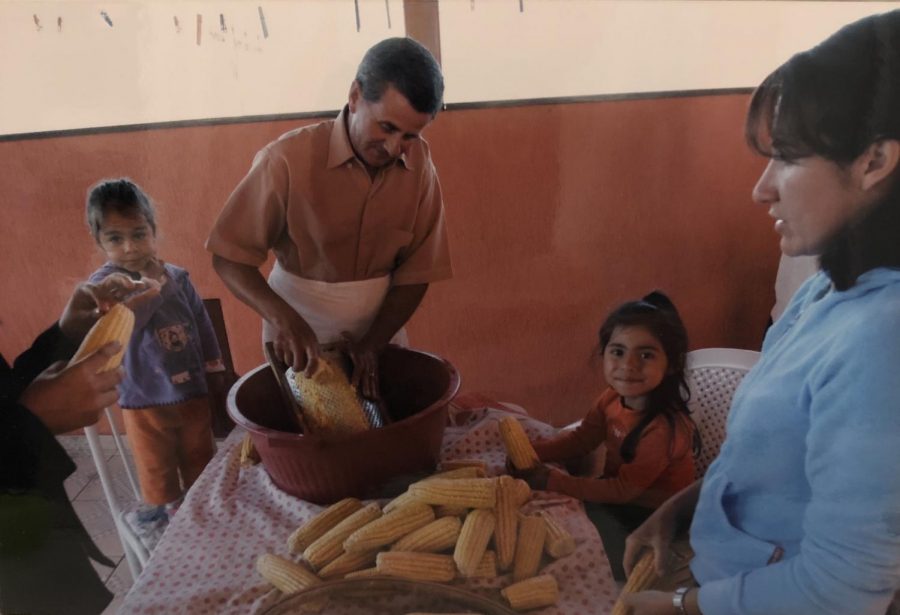

Pamonha is a traditional Brazilian dish made from boiled corn husks and sugar or cheese. Food often serves as a cultural connection between older and younger generations. (Photo by Sarah Gil)

April 28, 2021

At the age of three, my mother along with her parents and siblings made the permanent move from the small village of Poços de Caldas, Minas Gerais in the southeast region of Brazil to the very culturally different Harrison, New Jersey.

She would be labeled as a first-generation immigrant for her entire life, and therefore I inherited the label second-generation immigrant when I was born. However, our experiences with the word immigrant couldn’t be more different.

She speaks fluent Portuguese. I do not. She became a United States citizen when she was 30 years old. I was granted automatic citizenship upon birth. She is very closely tied to her identity as an immigrant. She lived on a farm, with dirt floors and tin roofs. I lived in a beautiful two-story home, with everything I could ever want and need at my fingertips.

Our one commonality was our shared love for Brazilian food. Food became the easiest way to relate to my foreign family members and the closest tie I had to my second-generation immigrant identity.

At the age of four, my mother brought me to her hometown in Brazil. I was barely aware of what other countries were like outside of the United States. Brazil was a whole new world to me.

I met my relatives that I had no idea existed outside of the little bubble containing my parents and I. Of course, I found it hard to communicate with them seeing as I didn’t speak Portuguese and was hardly capable of a culturally divergent conversation at four. However, an icebreaker presented itself, one I would encounter many times over the years.

Pamonha was my first memory of Brazil and my culture.

On that trip, my family members and I spent the entire afternoon on the roof, prepping pamonha. The traditional Brazilian dish is essentially a paste made from corn that is wrapped in boiled corn husks. Prepping the dish was simple yet sacred to my ability to connect with my family. I still vividly remember the event today; if I close my eyes, I see the tub of wrapped corn larger than me and the sunburnt orange roof crowded with my distant family. The cultural and language barriers between my relatives and I melted away after that experience. I spent the rest of the trip playing constantly with my cousins despite the fact that we couldn’t communicate. But that was okay, the pamonha was enough for us.

At age 10, I remember going to Seabra’s seafood market with my grandma, Josie, to gather materials for a traditionally Portuguese (but still good enough for the Brazilians) dish called bacalhau à brás. Josie refuses to allow her grandchildren to call her grandma because it makes her feel old, so I will refer to her according to her wishes; as Josie.

Unable to stand the pungent smell of fish I, of course, complained. Josie told me to keep quiet, and that eating bacalhau à brás was a privilege. As an obnoxious 10-year-old, I inquired further as to how consuming a smelly fish could be considered a privilege. She explained that when she was growing up, fish was too expensive for her family to buy and her meals usually consisted of whatever farm animal they could spare for the day. She told me more about how most of the Brazilian dishes I eat now were not typical of her Brazilian diet because they were too costly to make.

The little town she lived in, Poços de Caldas, the same one my mom was born in, was situated on a high mountain top, making it financially and physically unfeasible to go to the market for supplies, except on rare or special occasions. Leaving the mountain was so difficult that when my mother and aunt and uncle were born, it took them over a month to make it into town. Therefore, the date on their birth certificates are a month or more after their real birthday. The fish market trip sparked a conversation about an aspect of my mother’s life that I never knew.

At age 15, I was spending the night over at my grandparents’ house. Around midnight, I snuck outside my designated guest room to ransack the kitchen for snacks. To my surprise, so was my 79-year-old grandpa. My grandpa barely speaks any English and I barely speak any Portuguese, but interactions like this prove that language isn’t a barrier.

My grandfather told me he wanted something sweet to eat. Understanding this universal love for sweets, I exclaimed, “Me too!”

I assumed he would take out chocolate or paçoquita, a Brazilian peanut butter snack that I had recently grown fond of. Instead he grabbed corn meal, milk and an amount of sugar that would drop anyone’s jaw. As he began to mix the three ingredients in a bowl, I started thinking of ways to politely turn down the concoction knowing that the quantity of sugar wouldn’t allow me to sleep the rest of the night.

Josie eventually stumbled into the kitchen after hearing the ramblings of my grandfather and I trying to communicate in the other’s language. Assuming the role of translator, Josie explained that my grandfather was making fuba, which had been a substitute for things like chocolate and cake since they were too expensive and difficult to come by in their town. My grandfather grew up on fuba, and even now in his old age, his inner child still has a fondness for it. Josie explained that the reason he added so much sugar was because sugar was pricey in Brazil, so he rarely ate it as a child. Now as an adult in the United States, he has unlimited access to sugar. So, buckets of sugar for him.

The story nearly brought me to tears. Imagining my grandfather as a child being denied the simple joy of eating sugar was too much for me to bear. I realized how hard my grandparents’ upbringing was compared to my own. I couldn’t muster a response, so I just hugged him and tried fuba.

Food has shaped my life and my relationship with my relatives. Whether it was bacalhau à brás, pamonha, fubá, coxinha, arroz e feijão, lombinho or virado de feijão, the food on the table helped my family facilitate joy and create stories. Without us even realizing it, it would forge connections and bonds we could not have made without it. Some of my best memories growing up took place at the dining room table or in a kitchen.

“Food is a privilege,” Josie said to me over the phone. “And the bigger privilege is being able to sit down and share that food with the ones you love.”

Email Sarah Gil at [email protected].

deja merald • Apr 29, 2021 at 5:50 pm

Its a real miracle Till today i still imagine how dr 0love brought back my man after he had vowed never to set his eyes on me again. he had even set the date for his wedding with another woman before i contacted dr 0love.

He told me to leave everything to him because i told him if the wedding takes place i would commit suicide.

After he cast the spell for me my man came back to me and said he wants to still marry on that date and the woman he wants is me and am so happy to announce that our wedding is coming up in 2 weeks time and i am still in contact with dr 0love till date because he is a very powerful man and a man to be trusted. CONTACT DR 0LOVE ON whatsapp him on: +1 (201) 781-2375 You can also visit his FB page: https://www.facebook.com/Lovespellthatworkfastusa or view his website: ttps://doctor0lovespell.wordpress.com/