Sikander’s ‘Extraordinary Realities’ explores migration and identity formation

Pakistani artist Shahzia Sikander’s key works are on display at the Morgan Library until Sept. 26.

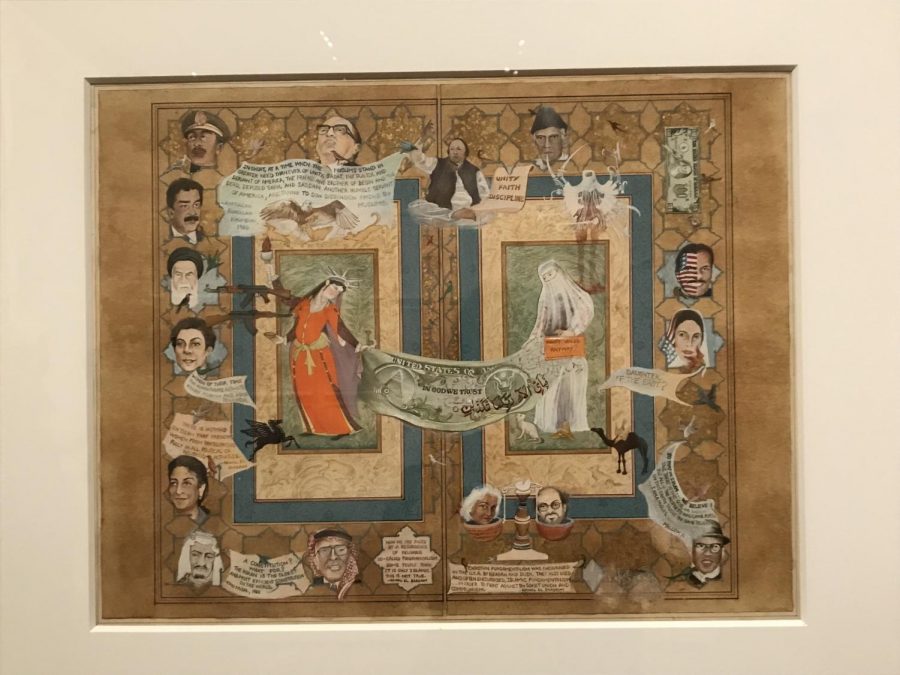

Persian artist Shahzia Sikander’s work is on display at the Morgan Library. The exhibition will be available to view until September 26. (Photo by Alexandra Christina Bentzien)

September 24, 2021

Before entering the Morgan Library’s gallery, visitors are greeted by a brief selection of older, traditional miniature paintings. This introduction to Pakistani artist Shahzia Sikander’s exhibition, titled “Extraordinary Realities,” remarks on the artist’s interest in exploring the development of cultural identities and racial narratives and the effect of colonial and post-colonial histories — all of which are viewed through Sikander’s focused perspective as a Pakistani woman.

“Extraordinary Realities,” on view until Sept. 26 at the Morgan Library & Museum in Midtown, showcases Hindu myths wherein a woman’s voice might take center stage. Sikander’s work within the gallery grapples with the discourse about devotion to tradition. As manifest in her reverence for the Indo-Persian art form, she has chosen to scrutinize the contemporary political and social systems that define those who share her cultural and gender identities and continue to influence the formation of diaspora populations.

The exhibition travels chronologically and geographically through Sikander’s works. It charts her career as an artist from her beginnings at the National College of the Arts in Lahore, Pakistan, to her studies at the Rhode Island School of Design, to her residencies in Houston and New York.

Though “Epistrophe” lacks the intricacy inherent to the demands of miniature painting, the installation showcases Sikander’s concern for the essence of composite artworks, which she experimented with in the animation “SpiNN.”

In “SpiNN,” Sikander layered drawings depicting a story of gopi rebellion. The animation seems to breathe; the images rise and fall as scenes fade and reappear to summon the mechanism of memory. The past floats to the surface to materialize in drawn histories passed along in an endless loop, mimicking the cycle of life itself: The story is born, evolves and revolves, comes to a close — only to be born again, refusing to leave without at least a faint trace.

The watercolor work of “SpiNN” exists in a two-dimensional form which, despite remaining still, oozes energy. With all of the rebellion’s scenes unfolding at once, images are stacked to blur the dividing lines of motion and chronology.

The many divisions encapsulate the works which detail Sikander’s experience and interest in diaspora populations, particularly the process through which identity shapeshifts to either accommodate, reflect or react to multiple cultures in conversation. Sikander asks how human movement leaves a mark within and against cultural, social, religious and political — particularly colonial and post-colonial — expectations and conventions. She expresses this in a unique portrayal of physical spaces whose limits she has tested again and again since the genesis of her career, specifically with her university thesis “The Scroll.”

A sense of transience permeates both “The Scroll” and “Epistrophe.” The earlier work sways with the haunting whisper of Sikander’s white gouache alter-ego ghost wandering between the many rooms of “The Scroll”’s domestic setting. In interacting with “Epistrophe,” viewers must confront a more tangible sense of transience, watching and listening to the scrolls flutter slightly as people pass by. The scrolls, laden with the signature motifs of Sikander’s work — circles, gopi, black-and-white checkered designs — harken to themes such as flight and interconnectivity. But there is no ghost to help the viewer navigate “Epistrophe.” The viewer becomes their own miniature figure, their own narrator unlocking questions of personal and collective identity in the face of the expansive work.

Sikander transposes the ideas from her miniature paintings onto a life-size canvas through which a viewer must understand how a person can possess multiple intersecting identities at once. If one looks long enough, not only do these most recent paintings encapsulate an entire life’s work of ideas, but the hanging scrolls of “Epistrophe” act as a mirror reflecting the fabric of humankind with all its varied layers. Sikander has her eye on the universe itself. Clearly, she is an artist in tune with the vastness of the human soul and the challenge of working through the assemblage of layers that comprise an identity. As many viewers simultaneously walk past the installation, one is reminded of other composite identities weaving through, and the influences that might remain with varying degrees of permanency.

Contact Alexandra Bentzien at [email protected].