With a bouquet in hand, Lady Liberty gets a radical makeover as a Black, non-binary transfemme person in Amy Sherald’s latest portrait, in her exhibition “American Sublime.” Her show is currently on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

The piece, “Trans Forming Liberty,” joins Sherald’s famed portraits of Breonna Taylor and Michelle Obama in the exhibition curated by Sarah Roberts, taking on a new level of complexity in light of current politics. Her distinct technique of painting gray-toned skin contrasting with colorful clothing and backgrounds persists across the entire collection. Spanning her 18-year career, “American Sublime” features a selection of almost 50 paintings. Sherald’s work captures the essence of individuals’ experience, challenging historical representations of Black Americans.

The floor is divided by thin walls into a cascade of white rooms,the pastel tones of Sherald’s paintings evoke a springy freshness. The elevator doors open to five portraits of Sherald’s typical bold subjects, each decorated with patterned clothing and ornamental jewelry. They are hung at eye-level, which complicates the painting-viewer dynamic. As we make eye contact with each of the figures, they return our gaze. Sherald’s 2017 oil on canvas painting “What’s different about Alice is that she has the most incisive way of telling the truth” embodies this duality exactly. It features a woman holding a 35mm film camera, adjusting the lens between her red fingernails as she shoots the viewers. It renders us frozen in time, much like how representations of marginalized communities have historically been portrayed by the art world: unchanged and overlooked.

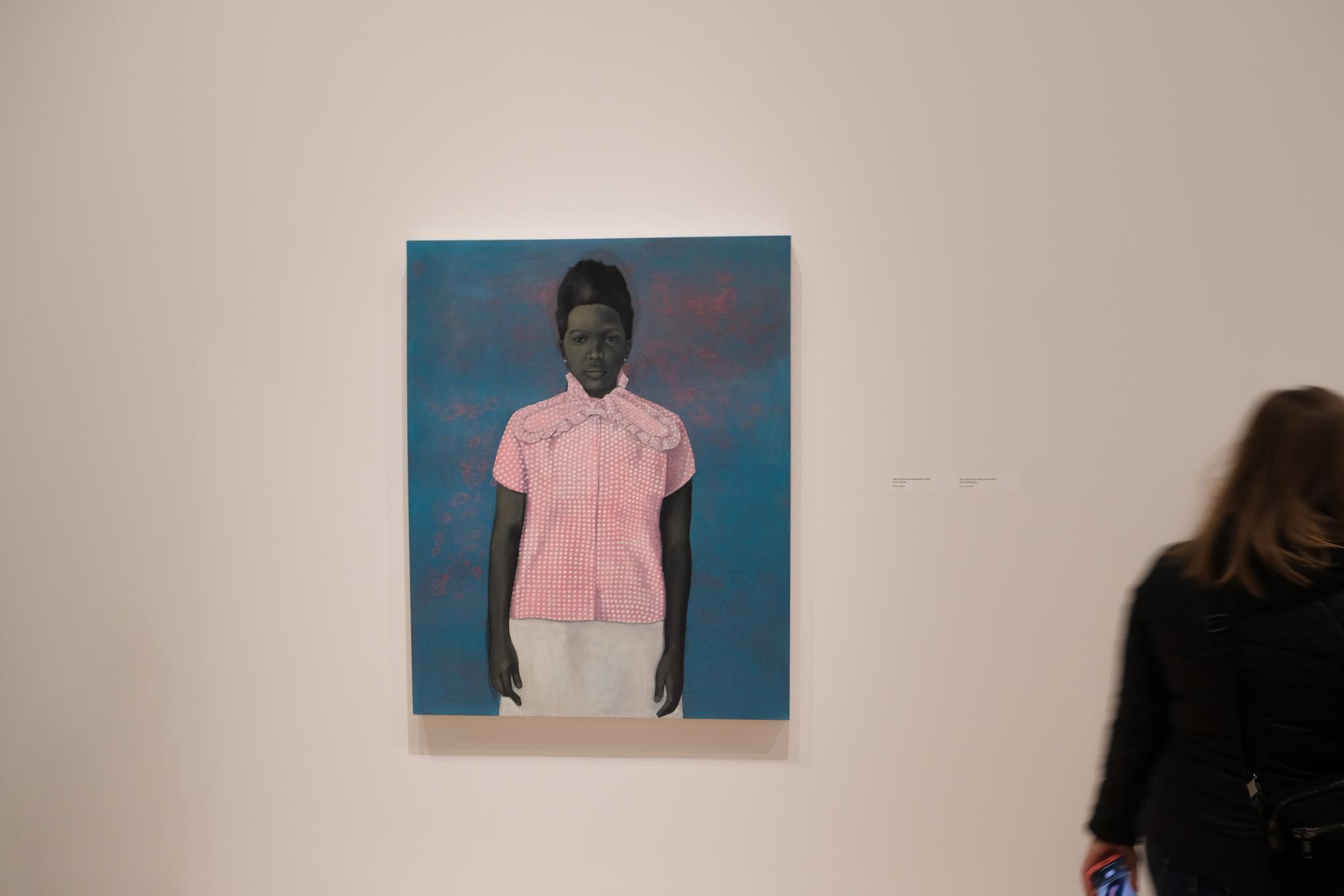

Oil paintings like “Well Prepared and Maladjusted” from 2008 and “Miss Everything (Unsuppressed Deliverance)” from 2013 embody Sherald’s interest in expressions of individuality. Both paintings depict subjects based on real people, unequivocally themselves: In “Well Prepared and Maladjusted,” the 6-foot-3 subject dresses like an overgrown toddler in a pink pussy-bow-tie top with white polka dots. The whimsical portrait “Miss Everything” evokes “Alice in Wonderland” imagery and plays with proportion as her subject grasps an oversized white teacup. As part of the exhibition’s overall concern with reflecting the interiority of subjects, Roberts opens the show with this selection of paintings to reflect Sherald’s talent for visual storytelling. Given the oppression of marginalized voices both in and around the art world, Sherald’s display of individuality is empowering.

Her early work provides helpful thematic context that allows audiences to thoroughly explore her more recent, impressive works. Whether it be because of their immense size or the heavy weight of the subject matter, her newest portraits are, by far, her most preeminent.

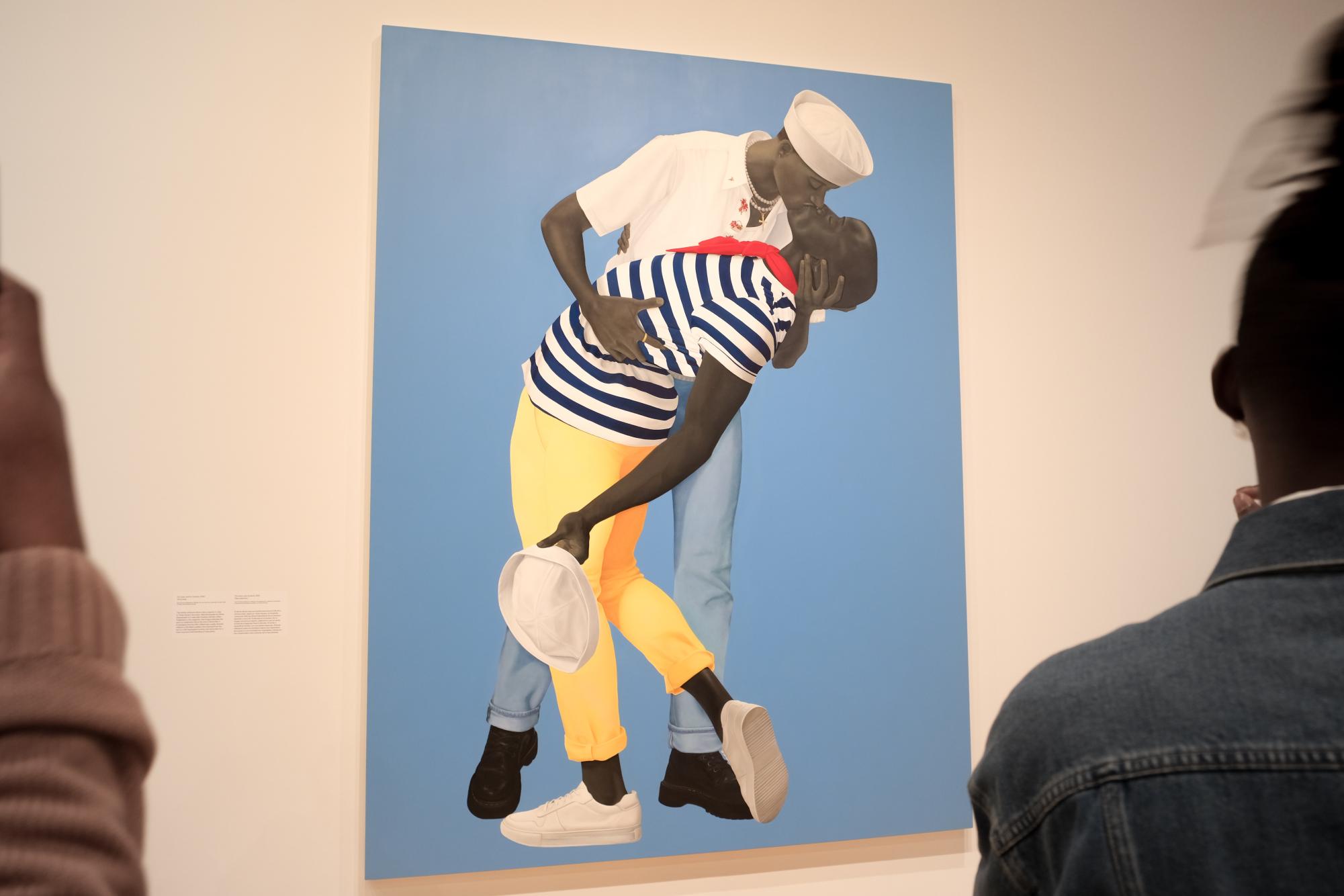

Take “For Love, and for Country,” Sherald’s oil on linen masterpiece from 2022: The painting is a recreation of Alfred Eisenstaedt’s iconic 1945 photograph, “V-J Day in Times Square,” only this time, the scene captures a Black, homosexual couple mid-embrace. The two men float against the blue background with their eyes firmly shut. The sailor figure clutches his partner tightly in both arms in this near-perfect replica. Sherald confronts taboos around homosexuality and “don’t ask, don’t tell” policies head-on in her portrayal of the lovers. The visibility of homosexuality, especially in people of color, is particularly poignant in a time when LGBTQ+ rights are under increasing threat.

By the exhibit’s end, the question of what “American Sublime” is to Sherald becomes clear. Her emphasis on imagery from American history reenvisioned with the inclusion of Black bodies and personal stories gets at the crux of what it means to exist in a marginalized body in the United States today. As Trump has issued an executive order for the removal of diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives across federal institutions, even private universities like NYU have felt its effects. “American Sublime” is in direct response with Sherald’s noting in an NPR interview: “We’re talking about erasure every day. And so now I feel like every portrait that I make is a counterterrorist attack to counter some kind of attack on American history and on Black American history and on Black Americans.”

Sherald’s show leaves viewers with a hopeful impression for the future as her subjects insist on being seen. A counter-revolution is coming, she warns, one painting at a time.

Contact Eloise Maguire at [email protected].