Anonymity erases authorship from works of art. Without a name, these individuals’ contributions end up forgotten. Throughout history, women visual artists have traditionally been subjected to this erasure. Under patriarchal constructions, women were expected to take on domestic duties, leaving little time for artistic exploration.

Founded by Susan Unterberg, the Anonymous Was A Woman grant program uplifts mid-career women visual artists over the age of 40 to counter this exclusion. The award makes woman-identifying artists’ work possible by reducing limitations that might restrict them from creating their work, providing resources such as workspaces and child care. Currently on display at NYU’s Grey Art Museum, the exhibition “Anonymous Was A Woman: The First 25 Years” presents the work of awardees from 1996 through 2020. The name of the award references a line in Virgina Woolf’s “A Room of One’s Own,” alluding to the many anonymous works that were created by women, and thus forgotten.

The exhibition at the Grey Art Museum excellently declares the power of this award to change the careers of female artists. In addition to their work, some of the artists’ reactions to receiving the award are quoted in the wall descriptions. This addition further allows the artists’ individuality and voices to enliven the exhibition space.

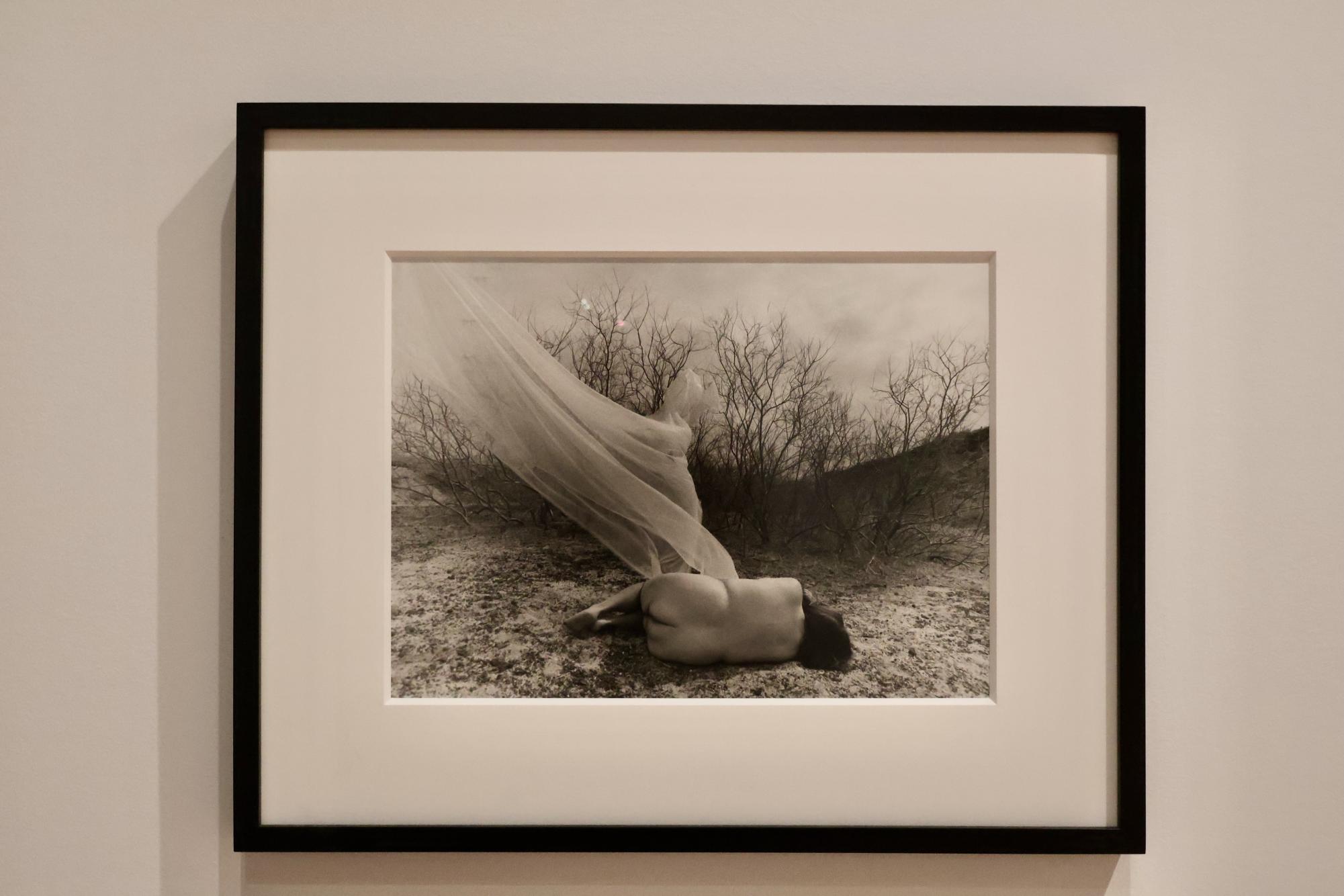

In one of the first pieces in the exhibition, “Stillness #25” by Laura Aguilar, the artist asserts her power of self representation through photography. In the self-portrait, the artist lays naked curled up in a ball with her knees tucked up to her head. The landscape is desolate and barren, filled with leafless thin trees. A white piece of thin fabric flows in the wind in the center of the image. Aguilar infused this image with the emotions she experiences while taking care of her dying father. She explains “stillness and dying made me think about how we find serenity, how we grow to discover grace in dying and in life.” Aguilar’s photograph is a reminder that if we experience life passively, we can too easily skip over important details of the present. Aguilar’s piece is a beautiful opening to an exhibition that refuses its artist’s abandonment and asks viewers to take a moment and closely observe the photograph.

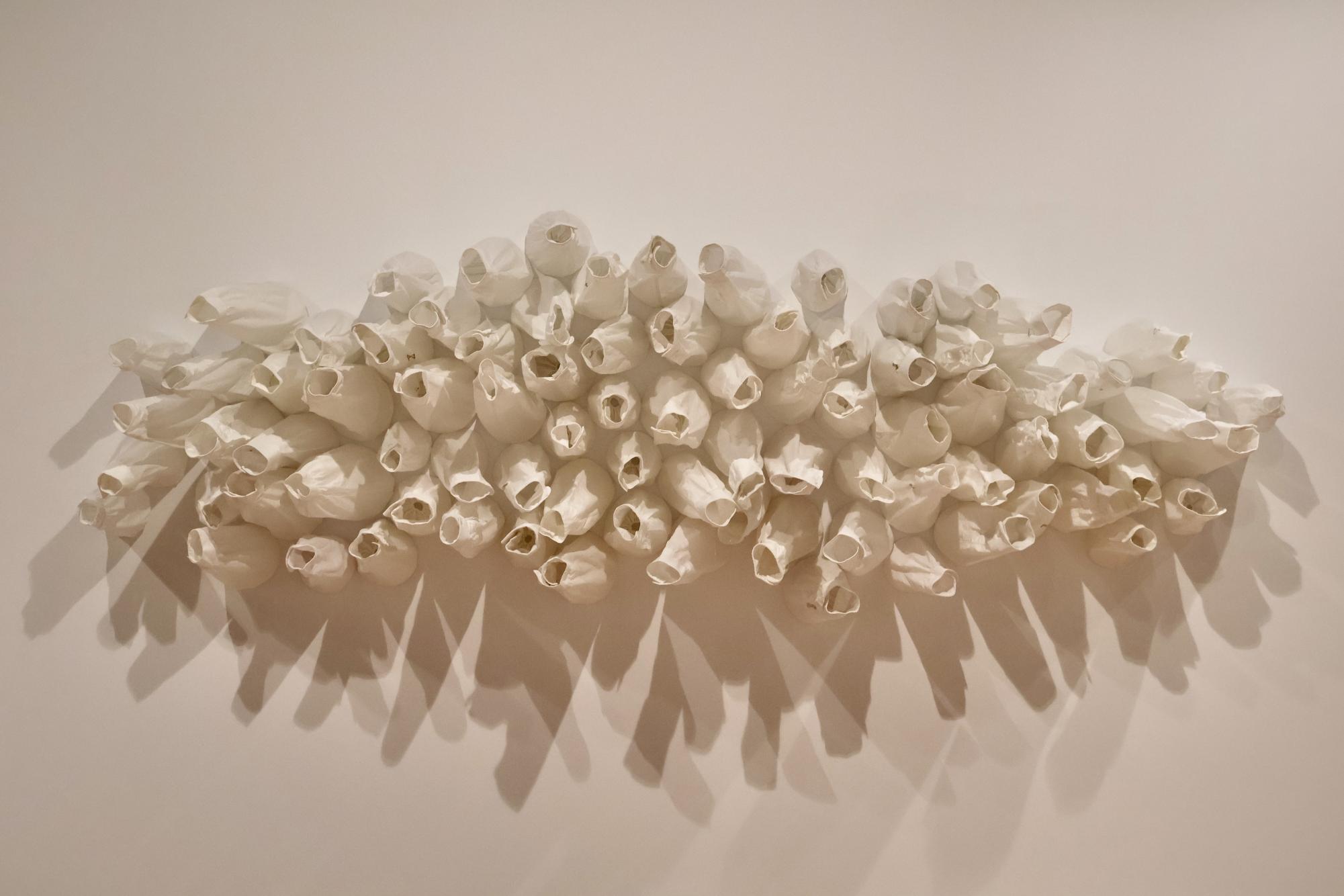

Another exploration of identity, Lynne Yamamoto centers the female inspiration she grew up with in “Ringaroundarosie.” Starched sleeves of white button-up collared shirts extend from the exhibition wall. They are grouped in an oval formation and resemble the shape of a collection of barnacles. The ends of the shirt sleeves have holes created by cigarette burns. The artist drew inspiration from her grandmother who was a Japanese immigrant and worked as a laundress. “Ringaroundarosie” is an acknowledgement of how our familial histories shape our personal journeys. In moments of triumph, it’s important to reflect on the generations that helped or suffered so future generations could one day succeed. In a similar manner, while many of the voices of past women artists have been silenced, the AWAW awardees’ creations work towards healing the disparities in the art world.

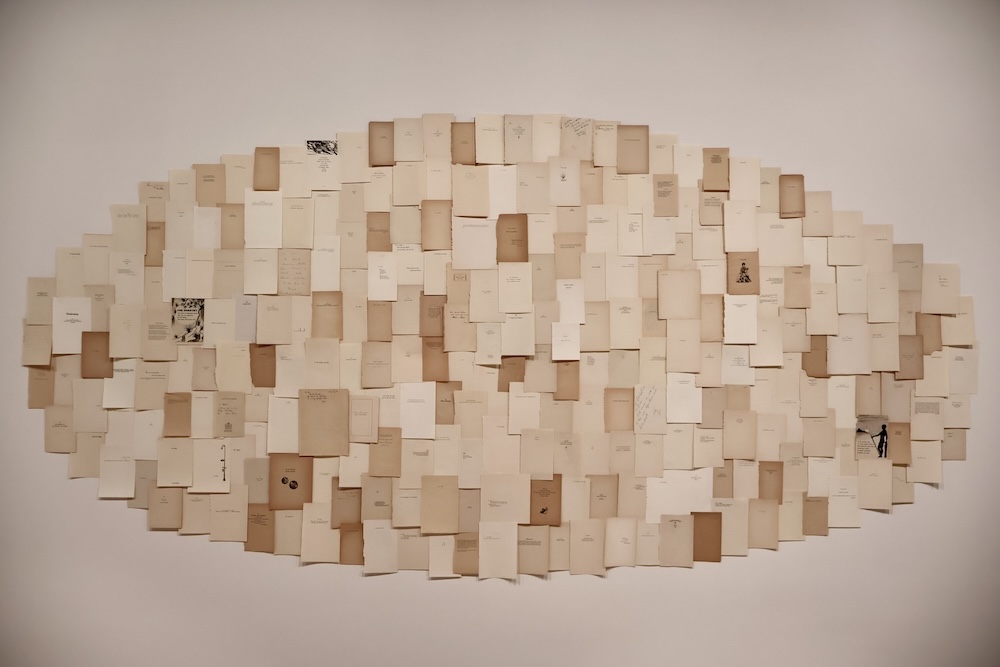

Made from found objects, “For To (X)” by Valeska Soares beautifully overlaps pages of antique books to represent the importance of memory through material. Spanning the exhibition wall, Soares’ collage takes the shape of a large oval shape created by dedication pages from books. In varying tones from eggshell to tan, some pages also feature small messages in the handwriting of the book’s former owner. These collections of pages represent pockets of love and empathy. While the pages could easily remain buried, once they are uprooted and presented, their charm is astonishing. The individuality of each of the pages is akin to the female artists represented in this exhibition. Each injects a distinct perspective, one that not only presents their artistic abilities, but also their ability to evoke an emotional response.

Spanning three large panels, Ida Applebroog’s work on canvas from “Monalisa” represents defiant sexualization of the female body. This work is an extension of the artist’s 160 drawing collection when she sketched her own vagina in privacy. It is a photo of a clay figure that the artist created during the period when she was making these sketches. The figure has a large square oval center, making the limbs appear irregularly small in proportion, and the genitals are visible. The skin of the body is rough and lumpy. The head of the figure features a short wig and a piercing confrontational gaze. The clay not only disfigures the female body, but the separation across the three large panels further fragments it. “Monalisa” resists sexualization through this deconstruction of mimetic representations of the female form that reinforce oppressive beauty standards. Applebroog takes on her own definition of objectifying the body. The figure turns the body into an object, a clay figure, but it isn’t meant to be indulged by the male gaze.

“Anonymous Was A Woman,” at the Grey Art Museum, masterfully presents the success and impact of the AWAW award. The artists claim the right to represent their identities and personal experiences within their work. They experiment with the traditional conventions of art-making to inspire new patterns of thinking. Once obscured, their artistic voices refuse to remain a mystery.

Contact Siobhán Minerva at [email protected].